Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Sutherland Serves as Lawmaker, Judge on Wagon Train; Gains Elective Posts in San Diego

By ROGER M. GRACE

139th in a Series

THOMAS W. SUTHERLAND’s 1839 admission to the Philadelphia bar and his evident legal aptitude, coupled with his father’s political connections, assured him of success in a law practice in Philadelphia—but that wasn’t his destiny. This Daniel Boone with a law degree was to make his way west. He would become the second district attorney to serve Los Angeles County…though historians have somehow failed to take note of his tenure.

As a lone rider, on a pony, Sutherland arrived in Wisconsin in 1835, when it was still Indian Country. He became U.S. district attorney there in 1841-45, after it had become a territory, and again in 1848-49 after Wisconsin was admitted to statehood. In August of 1848, gold was discovered in California, and the prospect of riches, and the certainty of adventure, beckoned. In 1849, Sutherland resigned his federal post to go west, with his wife, Joanna.

The Feb. 6, 1849 issue of the Daily Wisconsin contains an article bearing the headline, “WISCONSIN BRIGADE FOR CALIFORNIA.” It relates:

“We understand that from 400 to 600 persons will rendezvous at Madison about the 25th of March, and from thence form the line of march across Iowa and the Missouri plains to California. Among those who will join this company, we learn, are Col. Haraszthy (our State can scarcely spare so worthy a son,) Mr. Sutherland, Lieut. Wright, and various members of the Senate and Assembly, who are determined to visit this modern El Dorado and see its golden treasures. They will cross the prairie in one company, and under one organization, and though Wisconsin is the youngest State of the confederacy, we doubt whether any brigade that goes there will embrace a better class of men, or who will be more calculated to worthily build up a new government. Those with whom we have conversed are all enthusiasm to traverse even the long distance of 3,000 miles.”

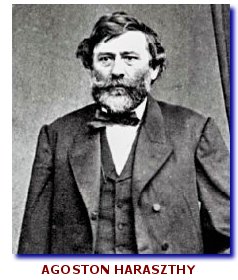

The man identified as “Col. Haraszthy” was Sutherland’s step-brother. Born in Hungary as Mokcsai Haraszthy Ágoston, he had served in that nation’s military—which was enough to gain him the courtesy title here of “Colonel.” He had been a nobleman in his home country, and, settling in Wisconsin, and adopting the name Agoston Haraszthy, he was commonly addressed as “Count Haraszthy.”

![]()

“There were five big wagons and fifteen teams of oxen in the train that Agoston led out of Madison in the first week of April 1849,” Brian McGinty’s 1998 book, “Strong Wine: the Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy,” says.

Oxen, not horses? Ill get back to that in a moment.

The book

notes that Sutherland and wife arrived in St. Joseph, Missouri, ahead of the Haraszthys, and that some of

those in the wagon train opted to go off to Council Bluffs, Iowa, inviting the Sutherlands to come with them to California by a northern route.

They declined.

Bluffs, Iowa, inviting the Sutherlands to come with them to California by a northern route.

They declined.

It was on May 15, 1849, according to the book, that Haraszthy and his troupe arrived in St. Joe, and Haraszthy “huddled” with his father (Sutherland’s step-father), Charles Haraszthy, and with Sutherland, and the three “decided that they would form a train bound for San Diego via the Santa Fe Trail.”

One of those who took the northern route was Lucius Fairchild, 18. He sent an account of his journey to the Wisconsin Argus in Madison, and it was published on July 17. His letter, dated June 3, was written while Fairchild was seated on the ground “[t]en miles west of Fort Childs” (later renamed Fort Kearny), in Nebraska, on the Oregon Trail. Fairchild’s account mentions:

“Mr. Sutherland has left us and gone by the way of Santa Fe with Haraszthy and three teams from Delavan [Wisc.]. He thought it the safest and most sure route, although it is three months longer. He may be right, but I do not think so.”

Fairchild and Sutherland both arrived in California in 1849. The former returned to Wisconsin, became a lawyer, and was elected governor there in 1866.

![]()

Accounts of the journey are preserved in the form of letters…such as an April 24 missive from Sutherland to a friend, written while in St. Joe, and published in the May 23 edition of the Milwaukee Sentinel.

The letter tells of a “large company of the F.F.V.’s”—that is, First Families of Virginia—who were “duly attended with their servants and iced champagne.” This was, however, early in the journey.

Sutherland proceeds to complain of a “starched set from Boston, who find their satisfaction in abusing Mr. Polk and his war, but yet with Yankee consistency are rushing to obtain the wealth of a country secured by the late administration.” The war with Mexico under the administration of President James K. Polk had resulted in the transfer to the U.S. of Alta California and territory that would comprise all or part of other western states.

On TV’s “Wagon Train” and in other depictions of the journeys westward, covered wagons are consistently pulled by horses. Sutherland’s letter says that the “majority of the emigrants” from Wisconsin “will go with ox team,” and pointed to one former denizen of the Badger State who had “come here with mules” but was “exchanging them for oxen.” The writer makes no mention of horses. “The sensible men drive oxen, the fancy ones mules,” the letter observes.

![]()

McGinty’s book relates that on May 19, “all the men of the train met around a campfire to appoint four of their number—Sutherland, Agoston, Charles, and a man named William A. Phoenix—to draft bylaws for the journey.”

There was, on wagon trains and in mining camps, established “law,” and, in fact, what were akin to court proceedings took place when necessary.

The book continues that “[o]n the evening of May 23, the first day out of Leavenworth [Kansas], the Wisconsin wagons made camp,” the bylaws that had been drafted were presented, and elections were held—with Agoston Haraszthy chosen as “captain” of the wagon train, Phoenix named as wagon master, and Sutherland as judge.

That was the only time Sutherland ever did serve as a judge—though he was frequently accorded the title of “Judge” in California, as were other leading attorneys. It was perhaps because he was so often addressed in that manner that the press erroneously recited upon his death in 1859 that he had been a judge in 1850-52 of the “Southern District of California,” referring to the First District, comprised of Los Angeles and San Diego counties. An account in the San Francisco Herald, picked up by the Los Angeles Star on Feb. 12, 1859, and repeated elsewhere, opines that the judgeship he never held was “an office which he filled with credit.”

All four men who made laws for the wagon train would all go on to be elected as the first holders of certain public offices in California. In pre-statehood balloting in San Diego County on April 1, 1850, Sutherland was elected county attorney, and “Count” Haraszthy as sheriff. Then came the initial elections for City of San Diego offices on June 16, with Sutherland chosen as city attorney and Agoston Haraszthy as marshal. Charles (born Károly) Haraszthy was one of five men placed by voters on the San Diego Common Council. (He also became the city’s first justice of the peace and, in that capacity, served as one of two associate justices of the county’s Court of Sessions, most of the powers of which were shifted in 1852 to a new body, the Board of Supervisors). Phoenix won the race in 1854 for the post of sheriff in the newly formed Amador County. (He was fatally shot the following year in Tuolumne County after chasing some bandits there.)

![]()

Back to the journey from Madison to San Diego.

A July 22 letter from Sutherland, published in the Sept. 22 issue of the Wisconsin Democrat, is less than laudatory of the latest stopping off point, Santa Fe, New Mexico, which the letter describes as “a collection of one-story mud houses.” It remarks:

“The place is infested with all kinds of vermin, including blacklegs [card sharps]. Gambling is the only amusement or occupation of the people; men and women playing together at monte, which seems to be the favorite game….This evening, Sunday, M’me Florey, the richest lady in the place, has a monte bank open and deals out her favors to scores of players. It is awful! The truth is, the Mexican men are all as devoid of courage as the women of virtue.”

Sutherland was fortunate that the foregoing statement did not surface when he ran for office in San Diego where voters included a number of men who were erstwhile citizens of Mexico. (Under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War, Mexican citizens in California gained automatic U.S. citizenship, unless they disclaimed it, by remaining in California for a year.)

Below Sutherland’s letter, as published in the Wisconsin Democrat, there appears one dated Aug. 7 from Agoston Haraszthy, from “Alburguerquz [Albuquerque], Valley of the Rio Grande,” reporting that his party was encamped along a river about 80 miles beyond Sante Fe. It mentions:

“Our friend Sutherland was invited by the respectable citizens of Santa Fe to remain in that place and practice his profession, which could yield him certainly $5,000 or $6,000 a year—probably more. Many heavy suits are daily brought and more in prospect. Mr. Holt, the lawyer of Sante Fe, received while we were there, $1600 in fee for [gaining an acquittal of] a worthless Mexican; and it is not ‘promise to pay,’ but cash down. But we had our sails spread for California and to that port we sail.”

![]()

And that port, the party reached. The March 2, 1850 edition of the Wisconsin Democrat says:

Sutherland did not return to Wisconsin “soon”…or ever.

He quickly found work in San Diego.

A letter which Fairchild wrote on March 17, 1850, to relatives back home (published in 1931 as part of a collection of his “California Letters”), says:

“Thos. W. Sutherland and Count H— arrived at San Diego this winter by the southern route & Tom is Alcalde of that place now. I heared that they lost all of their stock and were helped through by Uncle Sam.”

The day after that letter was written, Sutherland (actually, as acting alcalde) signed a document of historic interest. A 1939 Court of Appeal opinion recites:

“On March 18, 1850, Thomas W. Sutherland, as Alcalde of San Diego, deeded a certain tract to six persons.”

That tract, comprised of 160 acres starting at the water’s edge, was known as “New San Diego.” The price the town charged was $2,304, which was $90,800.00 in terms of 2009 dollars. (A one-eighteenth interest in the tract went to the lawyer for the investors, William C. Ferrell, who would become the first district attorney of San Diego and Los Angeles counties.)

Agoston launched a competing enterprise, located between Old Town and New San Diego. A deed to “Middletown” tract, comprised of 687 acres, was granted on May 27, 1850 by Alcalde Joshua H. Bean, who on June 16 would be elected the first mayor of what had just become a city. Sutherland, lawyer for that set of investors, derived a share.

Both enterprises failed to draw businesses and settlers from Old Town.

![]()

It was in 1850 that the Sutherlands’ only child, a boy, was born; that Sutherland was elected county attorney, then city attorney; and when Farrell resigned as DA for San Diego and Los Angeles counties and Sutherland was appointed as his successor.

Running in two separate races, he suffered two political losses on Oct. 7, the first election held after California had gained statehood on Sept. 9. Seeking the post of state attorney general, Sutherland came in fourth in a field of eight candidates, with only 203 ballots cast in his favor; the Democratic nominee, James A. McDougall, won with 10,405 votes.

The Oct. 21, 1850 issue of the Sacramento Transcript reports that in the San Diego race for the state Senate, John H. Warner “beat Judge Sutherland by one vote.”

An article in that newspaper three days later notes of the election: “The entire vote of the County did not exceed one hundred and sixty.”

Copyright 2011, Metropolitan News Company