Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Two Forgotten Early DAs for Los Angeles County Uncovered: Sutherland, Granger

By ROGER M. GRACE

137th in a Series

THOMAS W. SUTHERLAND and LEWIS GRANGER were district attorneys for Los Angeles County in the early 1850s—though you won’t find their names on anyone’s list of past DAs.

Like the “lost” episodes of the Honeymooners, they are “lost” office-holders.

I’ve told here, over the past four years, of the 36 men who are generally known to have held the office. Just as Grover Cleveland is listed as having been both the 22nd and 24th president of the United States because his two terms were interrupted by the administration of President Benjamin Harrison—and Jerry Brown, California’s 34th governor, will become the 39th—there are early DAs who appear more than once on the lists. Ezra Drown and Volney Howard each had two non-contiguous terms, and Cameron Thom had three.

If you take 35 holders of the office preceding the current DA, Steve Cooley, and take into account the four additional non-contiguous terms, that would put the incumbent, as the 40th DA in the county’s history.

However, as this column on Aug. 28, 2006, pointed out, one person on the lists of past DAs, Albert B. Chapman, elected in 1867, had been unnoticed by historians as having served as district attorney for about six months in 1863-64. He was appointed by the Board of Supervisors to serve out the second term of Drown, who died in office. So, it then seemed, Cooley was DA No. 41.

The DA’s Office responded by modifying its website to reflect both of Chapman’s stints in office.

Having now uncovered two more past DAs, I would reckon that Cooley is the 38th person to occupy the office, and is DA No. 43. But who knows? It is possible that in the days of this region’s infancy, there were yet other district attorneys who have been forgotten.

![]()

There were in the early 1850s settlements in the west far larger than Los Angeles, an erstwhile “pueblo” newly termed a “city.” Official happenings here were not ascribed with much importance, and record-keeping was spotty.

A report in the March 31, 1851, issue of the Sacramento Daily Union notes:

“It appears from the census returns, that the County of Los Angeles contains a population of about 4,000 persons—of which the city of the same name, has about 1,600. The county is well supplied with stock, there being in it about 100,000 head of horned cattle. And 12,000 horses.”

Such matters as attacks by outlaws were of far greater concern than making records for posterity. Nat B. Read’s 2008 book, “From Mountain Man to Mayor: Don Benito Wilson,” recites:

“The murder rate in greater Los Angeles for September 1850 to September 1851…was 1,240 per 100,000, an all-time record for an American town. The homicide rate would translate to exactly 319 times the current Los Angeles County murder rate of 3.89 per 100,000 residents.”

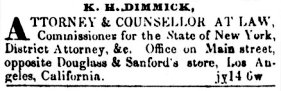

What’s more, being district attorney in those days was simply no big deal. The DA was at liberty to engage in private practice of law (assuming, that is, that he was admitted to practice—which was not a requirement of the office). Just as private lawyers today serve as part-time city attorneys of smaller burghs in this county, it was on an as-needed basis that the DA prosecuted cases and defended the county or the state in actions against them in the District Court. A classified ad for Kimball Dimmick appearing in the Sept. 18, 1852 issue of the Los Angeles Star mentions only in passing his government post. Here’s the ad:

![]()

The various lists of DAs who served Los Angeles County all start with William C. Ferrell. He was elected on April 1, 1850, a day when balloting took place in all 27 California counties.

What occurred on that date was not a “statewide” election, given that California was not yet a state (nor was it then, or ever, a territory). Balloting, in the course of setting up a government, was conducted in anticipation of statehood...which would become a reality on Sept. 9.

Under legislation enacted on March 2, 1850, there was to be “one District Attorney for each Judicial District.” There were, initially, nine districts, all being multi-county districts except the one for San Francisco. Ferrell was district attorney for the First District, comprised of the counties of Los Angeles and San Diego. Those counties were considerably larger than they are today including as they did terrain now lying in counties later formed: Orange, San Bernardino, Kern, Riverside, and Imperial.

District courts would remain in existence until 1880 (when they were supplanted by the county superior courts), but the districts did not continue each to be served by a single DA. Legislation enacted April 29, 1851, provided: “There shall be a District Attorney in each county in this State, who shall be elected by the electors of the County, at the general election of the present year, and the general election every two years therafter, and shall enter upon his duties on the first Monday of October subsequent to his election.”

The general election in 1851 took place on Sept. 3, and the initial district attorney of Los Angeles County, alone, was Isaac S.K. Ogier.

Ferrell is thought to have been the only “district attorney” for the First District. As to that notion, and other conceptions relating to the nascent government here, ’taint so.

![]()

“History of Los Angeles County” by Clarence Allen McGrew, published in 1880, seeks to list those who had held county and district offices since the first elections. It says:

“The first really complete record of election in Los Angeles county, now in existence, is that of September 5, 1855. Prior to that time, and at intervals since, the records are so very incomplete that it has been with great difficulty and at an outlay of much time and labor, we have succeeded in making the annexed lists of the several officers who have filled the various elective offices of the county, from the organization thereof, down to the present time. We have, however, the satisfaction of believing that the said lists are absolutely correct….”

The first four DAs for this county are listed there as follows:

“1850-51. Wm. C. Ferrell.

“1852. Isaac S. K. Ogier.

“1853. K. H. Dimmick.

“1854. Benj. S. Eaton.”

Through the decades, the names Ferrell, Ogier, Dimmick and Eaton have consistently been listed as the first four DAs for Los Angeles County, with some variations as to the years.

What I’ve found, however, is that Sutherland came between Ferrell and Ogier, and Granger was sandwiched between Ogier and Dimmick.

![]()

This is how it’s told, from the San Diego vantage point, in “District Attorney’s Office: A Brief History” an article in “Law Enforcement Quarterly,” Winter 1999-2000:

“Ferrell’s salary as D.A. was $2,000, plus 10 percent of civil awards collected, along with fees paid by the county treasury allowed by the court in every successful criminal prosecution. If you were convicted of robbery, the D.A.’s take of the $50 fine was $41. Ferrell lived well on this generous income until May 1851, when the state legislature caught on and cut the salary down to $500 plus the criminal fees. Ferrell was so outraged that he quit on the spot.

“The same legislature decided to combine the jobs of D.A. and ‘County Attorney,’ known today as County Counsel. The outgoing County Attorney, Thomas W. Sutherland, was happy to become D.A. He wasn’t so happy a year later in 1852 when the County of San Diego went bankrupt and stopped paying him. He then moved to San Francisco.”

That’s an interesting yarn—rooted in earlier sources—but it’s largely fiction.

It’s true that legislation as to new salaries of state, district, and county officials was enacted on May 1, 1851—but that was months after Ferrell left office. Even if Farrell had still been in office, the legislation would not have affected him. It applied to “persons designated after the expiration of the term of office of the present incumbent.” (District attorneys in the southern counties of San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo were to receive $500 per year, while the San Francisco DA, who presumably would have a larger workload, was to get $2,000 a year. DAs in Sacramento, San Joaquin and Yuba counties were to be paid $1,500 per annum, while the rate in other counties was set at $1,000.)

Right about the time Sutherland supposedly took office as San Diego County district attorney is when, in actuality, he left office as district attorney for the First District, moving to San Francisco in mid-1851, not in 1852.

It was the City of San Diego, not the County of San Diego, that went bankrupt. Sutherland—who was elected city attorney on June 16, 1850 (after being elected county attorney on April 1)—did not go off in a huff because his pay was cut off. Donald H. Harrison, in his 2005 book, “Louis Rose, San Diego’s First Jewish Settler and Entrepreneur,” points out that on May 15, 1851, “[t]he salary of city attorney was abolished, but this was merely symbolic, as Sutherland had not been collecting a salary.” The author cites the minutes of the Common Council for Jan. 23, 1851 in reporting that Sutherland had waived the $500-a-year stipend provided for the office.

By the way, the post of county attorney was not identical to that of today’s county counsel, who handles only civil matters. The county attorney was required by statute to conduct “all prosecutions for public offences” in the county Court of Sessions, presided over by the county judge and two justices of the peace. (The court had statutory “jurisdiction throughout the County over all cases of assault, assault and battery, breach of the peace, riot, affray, and petit larceny, and over all misdemeanors punishable by fine not exceeding five hundred dollars, or imprisonment not exceeding three months, or both such fine and imprisonment.”)

![]()

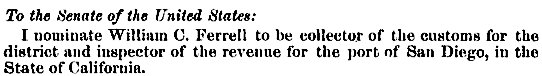

By the time Ferrell exited as district attorney of the First District, he was already working at another job. The Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States, Volume 8, reports that on Sept. 28, 1850, President Millard Fillmore sent this message:

That was on a Saturday. The following Monday, the nomination was approved.

Ferrell did not resign at that point, however. To the contrary, he was re-elected district attorney one week after being confirmed as federal customs inspector.

It is almost certain that at the time of that election, Ferrell had not received word of his confirmation. Indeed, voters on Oct. 7, 1850—in choosing members of the Senate and Assembly, an attorney general, superintendent of public instruction, Supreme Court clerk, and district attorneys in six judicial districts, including the First District (oh, and in San Francisco, a harbor master)—had no knowledge that statehood had been granted 28 days earlier. The latest news they had was that favorable action had been taken in the Senate.

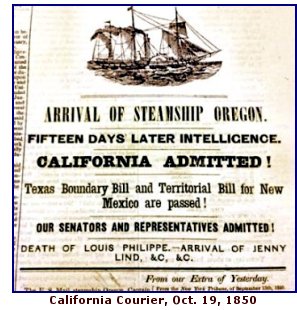

This was a time when news from afar was brought in via steamers. Those vessels coming from the east coast had to round the horn. A special edition of a San Francisco newspaper, the California Daily Courier, reports on Friday, Oct. 18 (and repeated the following day):

the horn. A special edition of a San Francisco newspaper, the California Daily Courier, reports on Friday, Oct. 18 (and repeated the following day):

“The U.S. Mail steamship Oregon, Captain Patterson, came into the harbor to-day, about 12, M, with colors flying and cannon booming bearing the glad tidings of the admission of California into the Union. Flags were instantly hoisted by the shipping in the harbor, at the Custom House, Courier Office, and several other places. The multitude on the hills, in the vallies, and on ships and housetops welcomed the news with loud huzzas. Captain Patterson, with his gallant ship, has the proud satisfaction of bringing this joyous news to our State.”

The Monday, Oct. 21 edition of the Sacramento Transcript heralds:

“The news of the admission of California arrived in the New World, on Saturday morning last about half-past three o’clock. It was announced by the firing of guns, and through the efforts of an individual, who with commendable public spirit, mounted a caballo and dashed up one street and down another, using his stentorian lungs to arouse the citizens from their sleep to a realization of their actual condition, as members of the recognized State of California.”

![]()

The Oct. 7 election for DA is not alluded to in any of the books I’ve seen on histories of Los Angeles or San Diego counties. Entries in the minute book for the District Court show that Ferrell remained DA through the winter of 1850, and from that, it can be inferred that he won the election. But who, if anyone, ran against him? That’s not easily ascertained. There was no newspaper in either Los Angeles or San Diego counties then; the Secretary of State’s Office has no information; and, incredibly, records of the registrar-recorder’s office in both counties go back only to 1943.

The Nov. 7, 1850, issue of the Sacramento Transcript, reporting results in other races in San Diego County—including Sutherland’s loss of a state Senate seat by a vote of 77-76—says that, in “round numbers,” about 160 ballots were cast in that county. The figure for Los Angeles County wasn’t known.

Last Thursday, I located results in the bi-county race for First District district attorney—but only for San Diego County. In leafing through editions of the California Daily Courier, in the archives of the Huntington Library, I found in the issue of Oct. 22 that Ferrell, with no opponent, received 150 votes.

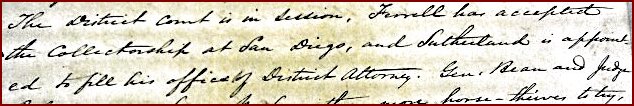

On Feb. 4, 1851, Granger—an inn-keeper, former preacher, and future district attorney—wrote a letter to Abel Stearns, a prominent rancher who held various political offices at various times, and was then a member of the state Assembly. The letter, also residing in the archives of the Huntington Library, says: “The District Court is in session. Ferrell has accepted the collectorship at San Diego, and Sutherland is appointed to fill his office of District Attorney.”

Snapshot of a portion of a letter at the Huntington Library, in collection of "Papers of Lewis Granger, 1851-1874,"

mssHM

68220-68241.

Minutes of the District Court for Jan. 10, 1851, recite that Ferrell “had resigned the office of District Attorney” and that District Judge Oliver S. Witherby had appointed Sutherland “to fill the vacancy occasioned by said resignation.”

In future columns, I’ll tell more of Sutherland, then go on to Granger.

Copyright 2010, Metropolitan News Company