Monday, September 20, 2010

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Garcetti Fights to Retain DA’s Post…and Resorts to Falsehoods

By ROGER M. GRACE

135th in a Series

GIL GARCETTI fought hard in 2000 to retain his crown as district attorney. But the public was weary of him, and a glib, low-keyed 52-year-old deputy district attorney, Steve Cooley, impressed voters as being right for the job.

In the March 7 primary, Cooley led the field of three candidates, garnering 38.3 percent of the vote. Garcetti drew 37.3 percent, and Deputy District Attorney Barry Groveman attracted 24.4 percent.

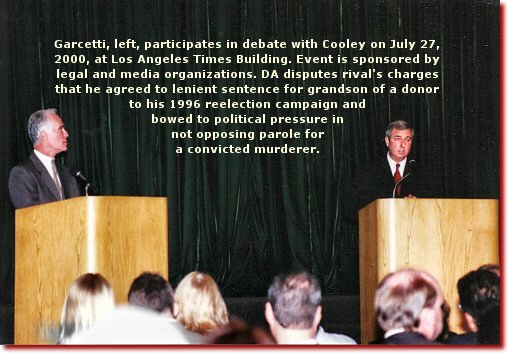

Prior to the primary, Garcetti barely campaigned, and spurned his opponents’ challenges to debate. But then, on April 27, he did a turn-about and called upon Cooley to participate in a public confrontation once a week. That didn’t come about, but the combatants did have at it quite a few times. Cooley’s campaign manager, John Shallman, is quoted in the Oct. 6 issue of the MetNews as saying that the rivals had agreed to a total of 18 debates, while the Nov. 3 issue of the Los Angeles Times alludes to the “15th and final debate” between the two having taken place at KCET the night before.

I saw one of those debates. It was before the Italian American Lawyers Assn. Cooley was calm and confident as he assailed the incumbent’s record. Garcetti took the blows badly; at one point, he actually looked as if he were about to cry.

A “media blitz” in the last 11 days of the campaign was not enough to bring Garcetti from behind. As he did four years earlier, he put on TV commercials concentrating on, and belittling, his opponent. However, his attempt to portray Cooley as a far right-wing Republican who was soft on crime fizzled.

One Garcetti commercial railed against “Republican Steve Cooley, the plea bargainer we can’t trust to be district attorney.” A counter-attack from Cooley cautioned: “No matter what Gil Garcetti’s negative campaign ads say, remember, it’s Gil Garcetti who’s saying it.”

Cooley won, with 63.7 percent of the vote.

![]()

Cooley had been a key supporter of Deputy DA John Lynch in his election challenge to Garcetti in 1996. Cooley had his fill of Garcetti, whom he previously supported, after one Brian John McMorrow entered into a plea bargain with the office in 1995.

Under the three strikes law, McMorrow could have been subject to a mandatory sentence of 25 years to life if convicted of his most recent offense. However, the DA’s Office had the option of striking a prior. Cooley’s general view was that the office was too infrequently exercising that prereogative, applying the law in a “draconian” manner…but it did strike a prior in McMorrow’s case, and in that instance, Cooley balked.

The defendant’s first two strikes were convictions for armed robbery. The latest offense was hardly a minor one; it was attempted arson. However, his grandfather, a Garcetti contributor—who donated $13,000 to Garcetti’s coffers in 1992—talked with the DA by phone, beseeching him to do what he could to help. (Garcetti later unsuccessfully urged the state Attorney General’s Office to secure phone records to determine how many conversations there were.) The defendant was sentenced to 16 months, and was in prison for less than a year before being paroled.

Garcetti’s version was that he told the contributor, B.J. McMorrow, that he couldn’t do anything, and a deputy later, on his own, agreed to a plea bargain, spotting weaknesses in the arson case.

Cooley didn’t buy that. He’s quoted in an Oct 27, 2000, Times article as recounting:

“You’re sitting there in the L.A. County D.A.’s office as a head deputy, and they’re putting pressure on you to put more and more petty thieves and drug possessors in for 25 to life, and at the same time, you have personal knowledge from credible witnesses that a special deal is being orchestrated for the grandson of a campaign contributor who committed one of the most serious crimes you can commit.

“You say, ‘Enough is enough here.’ That was like an epiphany.”

Lynch brought that case up during the 1996 race—but ineffectually. In his own campaign, Cooley drew attention to the case, and got his point across.

![]()

Lynch had been colorless, uninspiring, and unable to attract meaningful campaign funding. Cooley was not Lynch.

In the 2000 race, Garcetti drew contributions of about $1.2 million, while Cooley attracted more than $1 million.

The Times and the Daily News, the largest circulated newspapers in the county, endorsed Cooley.

On the day he announced his candidacy—Oct. 6, 1999—Cooley was able to boast of endorsements by Los Angeles County Supervisor Mike Antonovich (whose exasperation over Garcetti’s failings were recounted in the last column), retired California Supreme Court Justice Armand Arabian, and a man Garcetti once worked for, former District Attorney Robert H. Philibosian.

Philibosian accompanied Cooley to innumerable public events, introduced him to persons who could help him, and acted as his mentor. He’s been performing a like role of late in Cooley’s present campaign for the post of state attorney general.

(If Cooley does win in November, and the Board of Supervisors turns its attention to appointing a new DA for the next two years, it could do no better than to pick Philibosian, as it did in 1982.)

Although the post is a nonpartisan one, it was meaningful that Philibosian’s predecessor, John Van de Kamp, a Democrat, endorsed Republican Cooley over fellow Democrat Garcetti. Van de Kamp recalls:

“Gil had had two terms and I thought that was enough. I think it’s good to have fresh blood in there, generally.”

Van de Kamp, whose election as attorney general created the vacancy Philibosian filled, had (and has) considerable stature. Former DA Ira Reiner, whom Garcetti defeated in 1992, also endorsed Cooley, meaning that Cooley could claim the backing of all three former DAs.

![]()

Garcetti bagged—then lost—a key endorsement. The Los Angeles Police Protective League on Oct. 19 announced it was shifting its support from Garcetti to Cooley. The next day’s issue of the MetNews quotes PPL President Ted Hunt as linking the action to Garcetti’s leniency toward former LAPD Officer Rafael Perez.

It was Perez whose theft of cocaine from an evidence locker room triggered the Rampart scandal, implicating scores of officers in the Rampart Division and resulting in 106 convictions being upset.

Under a plea bargain, which required testimony against other officers, Perez received a five-year sentence, and was slated to be released the next year after serving slightly more than two years. The article quotes Hunt as saying:

“Mr. Garcetti has failed in his duty to weed out bad officers. Instead he has struck the deal of the century with Rafael Perez, the poster child of crooked cops. Perez is Garcetti’s star witness...[and] there is no credibility in that type of witness.”

![]()

Cooley hit hard at those issues that any challenger would have been expected to raise, including laggardness in responding to the Rampart scandal. He pointed to the failing of Garcetti’s office in its duty to pry support from parents not complying with child support orders (this county having the lowest success rate in the state). Cooley pointed to Garcetti’s reluctance to probe possible criminal wrongdoing in connection with the Belmont Learning Center fiasco, which entailed $175 million being spent on construction of a high school before the project was halted because it was discovered the soil was contaminated with toxic waste. (There was an eventual decision made not to launch any prosecutions.)

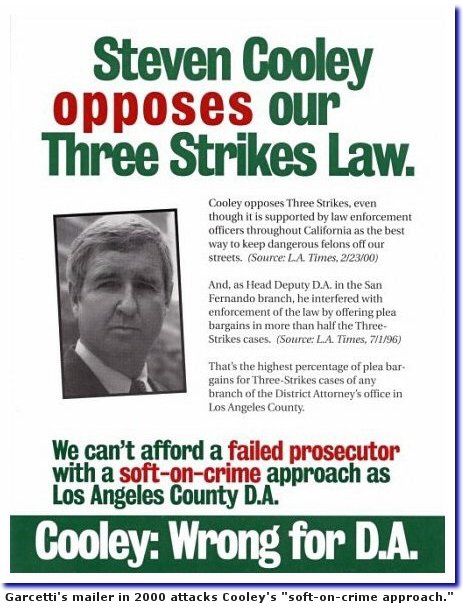

Garcetti hit hard…but below the belt. Having no real issues to use against Cooley, he relied on falsehoods, going so far as to cite sources which did not substantiate the assertions. Below is a reproduction of one mailer (in which Cooley’s face is darkened, in the original):

It asserts:

“Cooley opposes Three Strikes, even though it is supported by law enforcement officers throughout California as the best way to keep dangerous felons off our streets. (Source: L.A. Times, 2/23/00).”

The Times’ issue of Feb. 23, 2000, does not mention support of the Three Strikes law by law enforcement. More significantly, it does not say that Cooley opposes Three Strikes. It quotes Cooley as declaring, in an interview with Times reporters that “[t]he three-strikes law is an area that needs a heavy dose of proportionality,” explaining:

“If a new crime is a serious or violent one, and it’s been committed by a person who has two or more serious or violent felonies in his or her background, we’re looking at 25-to-life in most cases. [But] if the new offense is not a serious or violent felony, as a general rule, the presumption should be they should be treated as not a 25-to-life candidate, but as something less.

“Having someone go off to prison for a small petty theft, for a small possession of drugs or narcotics, 25-to-life is, in virtually all cases, wholly disproportionate and I think would breed a certain amount of cynicism among certain groups. And they become even more cynical when they see relatives of major campaign contributors committing really serious offenses who have two or more prior strikes, getting minimal sentences. I’m talking very specifically about the Brian John McMorrow case.”

The leaflet also says of Cooley:

“As Head Deputy D.A. in the San Fernando branch, he interfered with enforcement of the law by offering plea bargains in more than half the Three-Strikes cases. (Source: L.A. Times, 7/1/96).”

The Times did not comment in 1996 that Cooley “interfered with enforcement of the law.” It did not even refer to him by name. And, the figure is twisted. If you look at the article, you’ll find it says:

“Because each supervising prosecutor is given authority to make three-strikes decisions, a defendant’s chances of pulling a reduced sentence vary radically depending on the courthouse. In some, such as San Fernando, a three-timer is more than twice as likely to get a prosecutor’s plea bargain than in others such as Norwalk, dubbed ‘No Walk’ for being tough on defendants.”

The article does not say that in San Fernando, priors were stricken in more than half of the three strikes cases; it says that more than twice were stricken there than in such places as Norwalk. So, hypothetically, if priors were stricken in 10 out of 100 such cases in San Fernando and four out of 100 in Norwalk, it would mean that it was “more than twice as likely” that a prior would be stricken in San Fernando.

![]()

Another mailer declares:

“District Attorney Garcetti’s work has helped push crime down dramatically during his term as D.A. (Source: California Department of Justice).”

For Garcetti to take credit for the drop in crime in Los Angeles County was a bit audacious. A decrease in crime was occurring nationally.

A May 18, 1998, article in the Los Angeles Times reports: “Violent crimes such as murder, rape, robbery and aggravated assault fell by 10% in Los Angeles last year, reflecting a nationwide downward turn within cities of at least 100,000, according to preliminary FBI statistics released Sunday.”

A December, 2000, (that is, post-election) California Department of Justice report entitled “Why Did the Crime Rate Decrease Through 1999?” begins by noting something Garcetti must have known back when his pamphlet was issued:

“The overall crime rate has been decreasing nationally (and in California) since 1991.”

Garcetti also sought to portray Cooley as unethical for accepting contributions from lawyers and judges. I’ll deal with that in the next column.

Copyright 2010, Metropolitan News Company