Wednesday, September 1, 2010

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

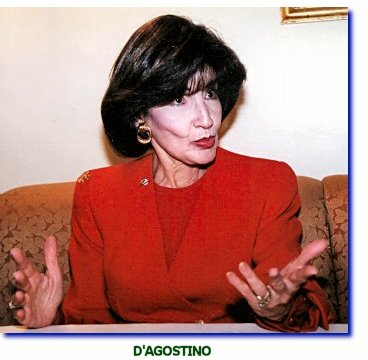

‘Dragon Lady’ Breathes Fire at DA Garcetti for Depriving Her of Case She Nurtured

By ROGER M. GRACE

132nd in a Series

GIL GARCETTI faced allegations, while district attorney, of vindictiveness toward deputies who were threats to him, politically. Below are the tales of two deputies who took him on in the arena of the Civil Service Commission, and lost.

●Lea Purwin D’Agostino: She’s known as the “Dragon Lady.” She was so dubbed by the “Alphabet Bomber,” Muharem Kurbegovic, whom she and Deputy DA Dinko Bozanich successfully prosecuted in 1980 for three murders, the deaths caused by his setting off a bomb at Los Angeles International Airport.

D’Agostino handled other

notable prosecutions—including that of director John Landis, charged with

manslaughter in connection with deaths on the set of “Twilight Zone—the Movie.”

It was the only case she ever lost.

D’Agostino handled other

notable prosecutions—including that of director John Landis, charged with

manslaughter in connection with deaths on the set of “Twilight Zone—the Movie.”

It was the only case she ever lost.

There’s one major prosecution she was assigned to handle, and wanted to go to court on, but the case was yanked from her in 1997 notwithstanding that she had invested extraordinary effort in it. It was the prosecution of Glen Rogers, who also had a nickname: the “Cross Country Killer.” In each of five states, from the east coast to here, he murdered a woman, each in her 30s.

In September of 1995, he met Sandra Gallagher in a Van Nuys bar. He persuaded her to give him ride home. He raped and strangled her and set her on fire in her truck. I’ve seen a photo of her charred body. It’s horrifying.

Why was the case snatched from D’Agostino? The reason can’t be proven, but it would certainly appear to be an instance of Garcetti retaliating against someone who had politically opposed him, and who might be a political threat to him in the future.

If you didn’t see my last column on Garcetti, you might take a look at it online. It will put today’s recitations in perspective. Whatever Garcetti’s strong points were—and certainly he did have some—and whatever “bum raps” he incurred (such as losing the O.J. Simpson case by supposedly making a decision to move the trial downtown), there does appear to have been a major fault on his part. It was a propensity for making personnel decisions based on a quest to reward friends and punish enemies.

The snatching of the Rogers case from D’Agostino does seem to fit this pattern.

![]()

She had been assigned the case days after the slaying. Rogers fled and was apprehended in Kentucky. D’Agostino went there to attend a meeting, arranged by the FBI, of representatives from the five states where charges against Rogers were pending. It was decided that he would be extradited to Florida.

Though he would be tried there first, D’Agostino still wanted him back here afterward. A 1997 prepared statement by her—she doesn’t remember where it was used—explains:

“[S]ince inception [of the case] I believed that even if convicted there, it was crucial that he also be tried in California, not only because of the brutal murder he committed here and to give some sense of justice to the victim’s family, but as added insurance should any verdict obtained in Florida be reversed.

“To that end I contacted Governor [Pete] Wilson’s office and from November, 1995 until July 24, 1997, worked closely with his Legal Affairs office to obtain the defendant’s presence here.

“Despite insurmountable odds—despite all the naysayers predicting that no way would Florida ever agree to extradite Rogers here—despite him being convicted and receiving the death penalty in Florida—the Governor’s office and I persisted and it now appears we’ve won.

“I advised my supervisors on July 16th of this [year] and 8 days later I was abruptly advised the case had been re-assigned since it was a ‘major crimes’ case.”

It was, of course, a “major crimes” case when it was assigned to her in 1995.

![]()

D’Agostino had recently come into disfavor with Garcetti. She had participated in a quiet effort to persuade then-Los Angeles City Attorney James Hahn to challenge incumbent Garcetti in the 1996 election.

Garcetti was seated at the table with D’Agostino at a March 16, 1997, dinner and confronted her with the rumor he had heard: that she had acted in concert with Los Angeles Police Protective League Director Ted Hunt and other league officials in attempting to draw Hahn into the race. She acknowledged the truth of this. She was later to testify at a Civil Service Commission hearing that Garcetti “was not amused.”

Too, there was the prospect that D’Agostino would run for DA in 2000, just as she did in 1992, taking on her boss, District Attorney Ira Reiner.

It was on July 24, 1997, that Deputy District Attorney Roger Gunson, director of branch and area operations, came into her office to demand the Rogers file. As she now recounts it, she told him:

“I’m not giving it to you. If you want that file, you can go in my cabinet and get it yourself.”

He was insistent, D’Agostino says. “I’m 94 pounds, five-foot one-and-a-half inches,” she notes in telling of having ordered Gunson from her office.

Gunson retreated, but the file was subsequently obtained, and handed over to DDA Pat Dixon (who was later on the State Bar Board of Governors and remains a prosecutor).

Garcetti had incurred the enmity of the “Dragon Lady.”

![]()

Sandra Buttita was Garcetti’s chief deputy. She tells me that when the Rogers case was reassigned, Garcetti “was in Europe” and, she recounts: “I made the decision.”

D’Agostino now scoffs that it is “inconceivable” to her that the action would have been taken without Garcetti having the final say. Thirteen years ago, she put it more strongly in her statement, declaring:

“Mr. Garcetti’s Chief Deputy told the press the decision to reassign this case was not made by Garcetti and that this case went through the ‘normal evaluation process’!! That is so preposterous that I believe the needle on the polygraph machine would have seizures! Since when does a murder case get evaluated two years after the fact—after a Grand Jury indictment has been returned? (I presented the case to the Grand Jury to assist in the extradition efforts and show Florida we don’t, as is commonly perceived, take forever to get a case to trial here). Is the office implying we leave suspects in jail for two years before we evaluate the evidence against them? In my twenty years as a prosecutor I’ve never heard of this occurring before.”

A Daily News article of Aug 21, 1997, reporting on the Dragon Lady’s protest, observes: “D’Agostino’s accusations are the latest from several prosecutors who claim that they were the victims of political payback by Garcetti.”

![]()

D’Agostino filed a grievance with the Civil Service Commission.

The DA’s Office made an ex parte appearance, without notice, before Los Angeles Superior Court Judge John Reid, then supervising judge of the criminal courts, asking for, and getting, an order sealing all papers in the commission files relating to D’Agostino’s case.

A Nov 16, 1997, article in the Los Angeles Times notes:

“[O]ne source close to the case said that before signing the order, Reid may not have reviewed the entire file, which already had been presented to the commission and is said to include a three- or four-line summary of Rogers’ alleged involvement in the killing and D’Agostino’s role in the case—information that has been largely reported in the media.”

D’Agostino did not have hard evidence that Garcetti personally ordered her removal from the case, or that the removal was for the political reasons she asserted. She lost.

Dixon obtained a conviction and on July 16, 1999, Rogers was sentenced to death. He is presently residing in Union Correctional Institution in Raiford, Florida.

●Kevin Greber: A deputy district attorney who had the daring to put the head of his office on the spot, publicly, soon after incurred a five-day suspension and was denied a promotion.

The official reason for the discipline was that Greber, in being cited for a traffic ticket in August 1995, became abusive with the officer and tried to get out of the citation by invoking his status as a DDA. There had been a similar incident, involving another officer, in October 1994.

As Greber, now in private practice in Bellflower, recounts the 1995 incident, “mutual displeasure was voiced between the officer and myself,” and the officer complained about him to the DA’s Office. Initially, the “situation was resolved informally,” without a reprimand, but merely an advisement: “Let’s not get into conflicts with officers.”

![]()

The suspension might well have been warranted based on misconduct. However, suspicion loomed that the discipline would not have been imposed, that the promotion to Grade 3 would have gone through, if it had not been for Greber’s encounter with Garcetti at a Saturday morning office training session in December, 1995. Greber suggested to the DA that he should admit that he erred in awarding bonuses totaling about $43,000 to three prosecutors in the O.J. Simpson case, doing so at a time when rank-and-file deputies were faced with salary freezes, and to apologize to those assembled.

Greber says of the confrontation: “I enjoyed taking a principled stand.”

He adds that “most of the rank-and-file were very much in favor” of what he did.

The taunt by Greber reportedly precipitated an onslaught of questions and comments from other deputies.

After the meeting, the lawyer recalls, then-Deputy District Attorney Peter Bozanich (an antagonist of Garcetti, mentioned in the last column) came up to him and warned: “He’s going to get you.”

Greber says that “within 10 days,” the seemingly resolved complaint by the police officer “miraculously...was revived,” and he was advised that a suspension was in the works.

His suspension came in September, 1996. The denial of a promotion was said to be tied to Greber mishandling of a three-strikes case.

Greber says of Garcetti:

“He was the imperial DA. He was like the center of a wheel, with all the spokes going out from him.”

He terms the chief prosecutor “vindictive” and “dictatorial.”

![]()

Greber was passed over for promotion again in 1997. He complained to the Civil Service Commission, attributing his non-promotion to the clash with Garcetti at a training session, and a hearing was set.

He was to be represented by then-Deputy District Attorney Dinko Bozanich (brother of Peter Bozanich). But Garcetti filed an action to prevent the representation.

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Alan Buckner (since deceased) ruled that a deputy district attorney is statutorily barred from practicing law on the side.

Greber calls that a “legally flawed ruling.” He says that with the consent of the hearing examiner, a complainant may be represented by a layperson.

“If lay people can do it,” he asks rhetorically, “how can it be unlawful practice of law simply because the representative was a lawyer?”

Greber wound up representing himself.

In an Aug 25, 1998, article in the Los Angeles Times, staff writer Hugo Martin tells of events the previous day at a hearing:

“It was to be, in the little guy’s eyes, a real-life version of the courtroom showdown between actors Tom Cruise and Jack Nicholson in ‘A Few Good Men.’

“And indeed there was plenty of drama and tension Monday when the little guy, a dapper young deputy district attorney named Kevin Greber, grilled his powerful boss, L.A. County Dist. Atty. Gil Garcetti, during an unusual Civil Service hearing.”

Martin goes on to recount:

“At one point during Garcetti’s three hours on the stand, punctuated by verbal jabs and angry looks on both sides, Greber blew his boss a sarcastic kiss.

“ ‘He’s being cute so I’m being cute right back,’ Greber told hearing officer Philip R. Levine.

“But Garcetti did not crack. He did not, as in Greber’s movie scenario, yell out ‘You can’t handle the truth!’ and confess to misdeeds.

“Instead, he kept his cool, repeatedly rejecting the charge that he denied Greber a promotion and initiated an internal investigation of the 31-year-old attorney in retaliation for Greber’s criticism.”

The Aug. 25 issue of the Daily News quotes Garcetti as telling Greber:

“I still view your actions as primarily political, political in that you would like somebody else as district attorney, pure and simple.”

The article says Garcetti justified the five-day suspension on the basis of Greber having flashed his DDA badge, explaining:

“I’ve always talked about improper use of the badge...because I won’t tolerate it as district attorney.”

That same day’s issue of the Daily Breeze reports that Garcetti sought to explain his award of bonuses to the Simpson prosecutors by pointing to “the incredible invasion of privacy” they faced, adding:

“Right or wrong, I was trying to do something to help these three people.”

Greber says that the hearing officer found that there had not been retaliation against him. Nonetheless, he recalls, soon after that, his promotion came through, with him learning of it through a voicemail message from Garcetti.

Copyright 2010, Metropolitan News Company