Tuesday, July 27, 2010

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Garcetti’s Candidacy for Re-Election in 1996 Hampered by Heavy Baggage

By ROGER M. GRACE

129th in a Series

GIL GARCETTI had the advantage of name-recognition and incumbency, in addition to brimming campaign coffers, as he vied in 1996 with five challengers in the race for Los Angeles County district attorney. But he had “baggage,” and it was heavy.

So weighty was it that in the March 26 primary, the incumbent attracted only 37 percent of the vote, with second place being taken by Deputy District Attorney John Lynch, who captured 21 percent. Although Garcetti did glean a plurality, he started the general election race from behind, given that 63 percent of the voters had indicated they were of a mind to replace him.

Here’s what he had to overcome:

●Simpson Verdict: On Oct. 3, 1995, the jury in the prosecution of ex-football star O.J. Simpson in a double murder rendered a verdict of “not guilty,” an assessment belied by the evidence. As head of the office that lost the case, Garcetti was the person to blame, in the eyes of many. Most of the challengers pounded at the issue. Garcetti labeled his opponent in the runoff, Deputy District Attorney John Lynch, as “Johnny One-Note” for harping incessantly on that one theme.

●Three Strikes: There was perceived to be a lack of a cohesive policy on striking priors in what were initially dubbed “three strikes and you’re out” cases. Some decisions to seek life sentences where the third felony was a relatively minor one were seen as unjust. One Los Angeles Superior Court judge campaigned against Garcetti from the bench, lambasting him for seeking such a penalty in the case of a homeless man alleged to have been caught in possession of three-tenths of a gram of cocaine. (The diatribe by Judge David Yaffe received major press attention; the fact, unknown to Yaffe, that the defendant had serious unalleged priors, in addition to four parole violations, didn’t.)

●Political Influence: There was an allegation of favoritism having been accorded one defendant—grandson of a major Garcetti contributor—whose prior robbery conviction was stricken. Garcetti admitted to communication between the grandfather and himself, but insisted that, after a staff member looked into the matter, he told the contributor there was nothing he could do. The subsequent striking was an independent decision by the prosecuting attorneys, the DA insisted. The Office of Attorney General found there was nothing done out of the ordinary, but questions continued to be raised.

Right there, you have what could be viewed as three “strikes” against Garcetti—and it appeared that the DA might be “out” when the election was over.

These three controversies have been mentioned here previously. There were two others:

●Sagging Office Morale, a $42,807 Give-Away: The troops in Garcetti’s office were disgruntled. In light of county budget problems, there had been no pay hikes in four years. Yet, Garcetti quietly granted bonuses in 1995 to Simpson prosecutors Bill Hodgman ($17,760), Marcia Clark ($14,300) and Christopher Darden ($10,747).

Garcetti also told the trio to take the rest of the year off, with pay.

Veteran prosecutor Lea Purwin D’Agostino, now retired, is quoted in the Nov. 9, 1995, edition of the Times as declaring:

“I am beyond upset. And so is everyone else to whom I’ve spoken. I’ve never seen such a totality of anger.”

Rank-and-file prosecutors, envious and irate, were not mollified by a statement Garcetti issued to them on Dec. 5 saying that “never in my twenty-seven years in this office had I seen the personal lives of our prosecutors and their families invaded to such an outrageous extent by members of the media and public” as that suffered by the leaders of the Simpson prosecution team.

A Dec. 17, 1995, article in the Daily News relates that some prosecutors “took potshots at the trial strategy of the prosecution team; questioned what invasive public scrutiny Hodgman was subjected to; and noted that the invasion of privacy that garnered the Simpson prosecutors compensatory bonuses also drew them millions in book and potential movie deals.”

![]()

Hodgman, who acted in a supervisorial role, discloses that he initially spurned the offer of extra pay.

“I told [Garcetti] I didn’t want a bonus,” he says, relating that he suggested to the DA that he “take my share and distribute it among the other people on the team.”

Hodgman, who was director of central operations, recounts that at one evening meeting with Garcetti, “I was just too tired to fight him.”

He comments:

“I know Gil was motivated by a sense of doing the right thing….Gil was attuned to the price we were paying.”

Trying that case, he remarks, was “like being in a black hole from which very little light escaped.”

![]()

Even if Garcetti was, as Hodgman declares, “motivated by a pure heart,” he clearly made a bad call. He should have anticipated discontentment among the staff, who had gone without pay raises, as well as formal grievances being filed by prosecutors who had also handled complex, high-publicity cases but had garnered no bonuses.

D’Agostino was among those protesting (to no avail). She had handled the 10-month involuntary manslaughter trial of director John Landis and others based on deaths occurring on the set of “Twilight Zone—the Movie.” The prosecution ended on May 28, 1987, with an unanticipated defense verdict.

D’Agostino tells me she worked “a good 80 hours” a week during that trial but expected no bonus or overtime pay because she was “a professional doing professional work.”

But, she apparently felt later that if the Simpson prosecutors got bonuses, she should.

No prosecutor should ever get one, former DA Robert H. Philibosian declares flatly, saying: “You don’t pay bonuses in the District Attorney’s Office.” He points out that there’s “no legal provision” for doing so.

Perhaps reflecting an awareness of that, the post-trial extra pay that went to Hodgman, Clark and Darden wasn’t termed “bonuses,” but was characterized, administratively, as retroactive temporary pay increases. Yet, a bonus by any other name is still a bonus.

Once the fact of the bonuses emerged in November 1995, the DA’s Office pointed out that then-county Chief Administrative Officer Sally Reed had approved the disbursements in May. Reed was adept at making financial decisions, but there was no indication that the legality of the gifts had been run by the person who made legal determinations, then-County Counsel DeWitt Clinton.

Giving a bonus to Darden, in particular, was unpardonable. It was Darden who had pulled the monumental boner of having defendant Simpson try on the pair of gloves belonging to the slayer, which seemingly didn’t fit him…bolstering the odds, immeasurably, of a defense verdict. Darden had no authorization from higher-ups to do what he did; co-counsel Marcia Clark beseeched him not to do it. Hodgman calls it a “horrendous trial lawyer mistake” which “was not part of our plan.”

Following the shore leave, neither Clark nor Darden returned to the ship. Hodgman did, and is still on board.

![]()

The Association of Deputy District Attorneys conducted a plebiscite among the 1,025 DDAs and paralegals in the office, and ballots were counted on the evening of Feb. 6, 1996. The question was asked: “Do you approve of the way Gil Garcetti is performing his job”? There were 307 “no” votes and 232 ballots cast in Garcetti’s favor.

Those casting ballots

were also asked to indicate a preference among the six candidates. Garcetti

pulled the most votes. The Feb. 8 edition of the Times quotes him as saying

that the message that members of his office was sending was: “We want Gil to

continue to be the guy who leads us.”

Those casting ballots

were also asked to indicate a preference among the six candidates. Garcetti

pulled the most votes. The Feb. 8 edition of the Times quotes him as saying

that the message that members of his office was sending was: “We want Gil to

continue to be the guy who leads us.”

In light of the concommitant vote of no confidence, that was a rather brazen display of fact-manipulation. It’s true that Garcetti received the most number of votes in the straw poll: 232. (The next highest number—186—was drawn by Lynch.) However, the total number of ballots cast for candidates other than Garcetti was 288, 56 votes higher than the number going to Garcetti.

The message sent by the majority was: “We want somebody other than Garcetti at the helm.”

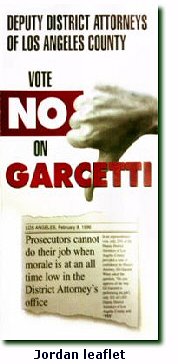

Garcetti was not the only candidate playing games with the figures. Deputy District Attorney Malcolm Jordan, a competitor in the primary, put out a campaign piece (at left) centering on the ADDA’s plebiscite. It claimed that only 23 percent of the deputies—232 out of 1,025—expressed confidence in Garcetti. That implies that 1,025 voted and that all who voted were DDAs. In truth, there were only 586 responses from both DDAs and paralegals who were queried, and 45 expressed no view. Even if the 45 who didn’t commit themselves are viewed as persons unwilling to go to bat for Garcetti, it’s a 40 percent vote of confidence, not 23 percent.

On Oct. 2, Garcetti, after fence-mending efforts, did score a victory in a new, post-primary intra-office straw poll, defeating Lynch by a vote of 303-269.

●Another Allegation of Favoritism: One “strike” came close to the end of the campaign. The Oct. 14 issue of Fortune magazine, which hit newsstands in late September, contains an article exposing Guess?, Inc.—maker of jeans—and the Marciano family that owned it. The article reports:

“In 1992…, Garcetti accepted $170,000 from Guess—one of the largest contributions to any politician in California that year. [Guess? Co-founder] Georges Marciano kicked in another $50,000 in 1995. Today the Marcianos have tremendous clout in getting the DA’s office to prosecute petty counterfeiters of Guess garments. ‘It’s almost like they’ve bought us,’ says Sterling Norris, a deputy DA who lost a primary race against Garcetti earlier this year. ‘The appearance is very gross. We’re prosecuting these cases, and there’s a real question as to whether we should be involved in them at all.’ ”

(Georges Marciano had sold his shares in the company to his brothers in 1993.)

In 1994, legislation was passed permitting trademark infringement, already a misdemeanor, to be prosecuted as a felony if 1,000 or more knockoffs were manufactured.

The article quotes then-Deputy District Attorney Sheldon Levitin, who had handled some Guess? cases, as complaining:

“This is a tremendous waste of scant resources. I’ve been working as a prosecutor for more than 32 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this, where a corporation has taken what would ordinarily be a civil matter or at most a misdemeanor, helped pander new legislation through both houses, and then powers the investigation, every aspect of it, and makes sure it’s filed by us. I’d much rather see deputies trying cases involving violent crimes rather than cases involving a commercial enterprise whose toes are being stepped on by a peddler. There aren’t enough courts; there aren’t enough judges.”

The Fortune piece says a supervising prosecutor, not named, who wanted to prosecute a Guess? counterfeiting case as a misdemeanor was ordered by a higher-up to file it as a felony—and later that day was visited by two Guess? investigators. The lawyer is quoted as remarking:

“I appreciate the fact, that Guess has a right to protect their interests, but I don’t think they have the right to take over the district attorney’s office. They pretty much dictate what we’re gonna do with their cases. I consider a rape a hell of a lot more serious than a pair of pants.”

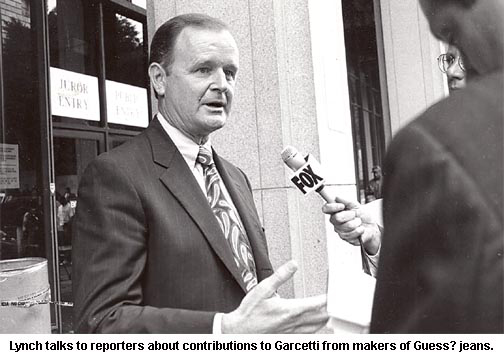

Lynch called a press conference on Oct. 2. The next day’s edition of the MetNews quotes him as saying:

“Filing deputies believe Guess Jeans has access that gets them felony trials that would otherwise be misdemeanors.”

Lynch said there “is a perception that this victim” of trademark infringement “is differently situated” from other manufacturers whose products are imitated, the article reports. He urged that the grand jury investigate, and that Garcetti return the money.

This passage appears from a letter to Fortune from Clifford Klein, acting head deputy in the Major Frauds Division:

“In every case in which Guess is a victim, there are other victims as well, mostly clothing and watch manufacturers who are competitors of Guess. We treat those cases seriously, and every victim, including Guess, is treated in the same manner.”

The MetNews article attributes to Lynch a reminder to reporters that he had set a $5,000 limit on contributions to his own campaign.

But did he actually observe that restriction? I’ll get into that in the next column, one that will examine Garcetti taking the offensive in the final weeks of the campaign and pulling off—but barely—a win.

Copyright 2010, Metropolitan News Company