Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

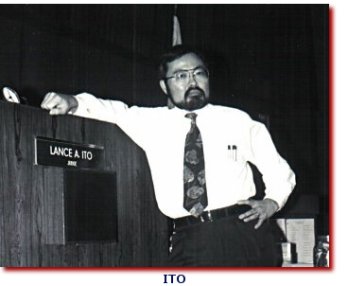

DA Garcetti Publicly Slams Judge Ito for ‘Vindictive,’ ‘Petty’ Monetary Sanction

By ROGER M. GRACE

127th in a Series

GIL GARCETTI did something a district attorney would not normally do: He publicly lambasted a judge presiding over a felony trial in progress. It happened on Sept. 13, 1995, near the end of the nine-month-plus O.J. Simpson trial. Garcetti, at a 12:30 p.m. press conference, laced into Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Lance Ito.

Yet a month earlier, Garcetti had presided over an office strategy confab at which it was decided—with the final word being his—not to take an action that might have resulted in the jurist stepping aside or being ejected from the case.

Lambasting the Judge: Bill Boyarsky’s Los Angeles Times column of Sept. 14 tells of the previous day’s incident:

“With the fiercest blast heard from his 18th-floor office since the O.J. Simpson trial began, Garcetti ripped apart his old colleague, Lance A. Ito, once a deputy district attorney, now the world-famous ringmaster of the Trial of the Century.

“Dropping caution, Garcetti condemned Ito for levying a $1,000 fine on the prosecution. Ito had fined the prosecutors $250 for failing to show up for an early morning hearing and when Deputy Dist. Atty. Marcia Clark objected, he quadrupled the penalty.

“ ‘What the judge did today was outrageous, it was vindictive, it was petty, it was uncalled-for,’ said Garcetti. He slammed his palm down on his rostrum for emphasis.

“It was a shocker for us who have faithfully sat through Garcetti’s monthly news conferences, often impatiently, while the D.A. fired off one generality after another.”

Garcetti was asked about a number of matters, Boyarsky recites, prior to a question to him about the monetary sanction Ito had imposed that morning. He quotes the DA as saying, “I’ll take a deep breath” before responding. The column continues:

“After calling Ito vindictive and petty, he said ‘this office will not pay this fine.’ If Ito doesn’t reduce it, ‘we will appeal.’

“A little later in the news conference, he said, ‘I’m not sure anyone can understand what this judge is doing....’ ”

On the afternoon of Sept. 13, Ito relented to the extent of restoring the initial sanction of $250 and, Boyarsky’s column says, “did it with a smile.”

![]()

Ito was

obviously in no position to comment publicly at the time. It’s now been nearly 15

years. I  e-mailed him a copy of

Boyarsky’s column and sought his reflections. Here’s Ito’s response:

e-mailed him a copy of

Boyarsky’s column and sought his reflections. Here’s Ito’s response:

“Frankly, I do not recall the incident or Boyarsky’s column. Getting lawyers to show up on time is a never ending battle, then and now. Early on during the trial it became evident that given the amount of media coverage it would be too distracting to pay attention to what was going on outside the courtroom. I had a group of 5 or 6 trusted friends whose job it was to bring to my attention any press coverage issue they might notice. Given the fact I had a sequestered jury, close attention to what the news media had to report was not high on my list of priorities. Given the fact that the trial had long ago exceeded the original time estimate I am sure my primary concern was to get the trial finished before losing too many more jurors.”

During a commonplace trial, a judge surely would not be oblivious to being lambasted by the district attorney at a press conference…and chances are that contempt proceedings would be brought. This, however, was a trial that was hardly a run-of-the-mill one; it was extraordinary, and grotesquely so. There was an international obsession with it. (On a ship in a fjord in Norway, I flicked on a TV set, and there, on the screen, was the Simpson trial.)

Perhaps Ito knew of Garcetti’s press conference at the time and, with all that transpired, doesn’t remember it. It’s also conceivable that it was never even brought to his attention. Ito had earlier been assailed at a press conference by chief defense lawyer Johnnie Cochran under circumstances that amounted to a clear contempt, yet shrugged it off. With the world watching, with emotions running high, Ito needed to maintain equilibrium, and did. Only one incident came anywhere near to triggering a contempt finding. The flap provided the title of a book, “In Contempt,” by the near-citee, Deputy District Attorney Christopher Darden.

![]()

Gripes expressed by Garcetti during the press conference are further delineated in a New York Daily News article appearing the same day as Boyarsky’s column. It reports:

“In his unusual outburst, Garcetti slammed Ito for everything from forcing prosecutors to jump-start their rebuttal case to complimenting the African-patterned ties worn by each member of the defense team.”

The article says Garcetti complained that Ito had barred Clark from wearing “an innocuous pin” depicting an angel, but commented, “nice ties” when lawyers for Simpson showed up “in ties that have obvious meaning to many in the African-American community.”

The article quotes the DA as declaring:

“If the defense does something, well, so be it. We do something, Bam!”

The word “bam” was punctuated by Garcetti slapping his hands together, the story relates. It proceeds to tell of the DA voicing his beef that Ito “hits us, and they’re hard hits, embarrassing.”

![]()

Whether Garcetti’s overall impression of Ito leaning in favor of the defense was accurate or not, the pin and the ties were “apples and oranges.”

Ito had forbidden the wearing of any emblems signifying support for any cause connected to the case. Members of the family of the defendant’s slain ex-wife were sporting pieces of jewelry with angels pictured on them. Defense lawyer Johnnie Cochran successfully protested that Clark’s pin symbolized support for them.

It was different with the neckties.

Seven members of the defense team came into court Sept. 11 wearing ties, six of them of the same pattern as the others and one slightly different, drawing the comment from Ito: “I see we are wearing team ties these days.” Later, this dialogue took place, in addressing a defense lawyer:

“MR. [PETER] NEUFELD: Good afternoon, your Honor.

“THE COURT: I’m fine. How are you? Nice tie.

“MR. NEUFELD: I am glad to hear that.

“MR. [ROBERT] SHAPIRO: Cheaper by the dozen.”

Unlike the pin—to which the defense took exception—the prosecution did not challenge the wearing of the ties...and if the ties were donned to convey some sort of message, the meaning of that message was obscure.

An Associated Press dispatch says: “The attorneys were tight-lipped when reporters asked about the neckwear....The only clue to the origin of the ties was a label on the back of one which said: ‘National Board of Critical Examination. Made in Ghana.’ ”

Dropping a Recusal Bid: It was just a month earlier that the District Attorney’s Office forewent an opportunity to try to force Ito off the case.

The prospect had arisen that Ito’s wife, Margaret “Peggy” York, then a captain in the Los Angeles Police Department (now retired), would be called as a witness.

By that point, the tapes had emerged which would-be screenwriter Laura Hart McKinny had made of LAPD Detective Mark Fuhrman reeling off his experiences as an officer…the tapes containing such recitations as:

“Yeah we work with niggers and gangs. You can take one of these niggers, drag ’em into the alley and beat the s—t out of them and kick them. You can see them twitch. It really relieves your tension.”

The admissibility of the tapes was in dispute.

The defense, obviously, wanted them in; Fuhrman’s rantings supported the defense’s theory that Fuhrman planted the bloody glove at Simpson’s residence, matching one at the murder scene, with Fuhrman, seemingly a white supremecist, having been propelled by racism to frame the African American Simpson.

Fuhrman’s explanation was, in essence: “Me, a racist? Perish the thought. I was just helping Laura concoct dialogue.”

![]()

York appeared to be someone who could substantiate the contention that incidents mentioned on the tape were fantasized. Fuhrman told of two heated encounters he had with York in the mid-1980s. With no conceivable reason to lie about it, with no known propensity for deceitfulness, York had stated under penalty of perjury that the incidents hadn’t occurred.

While it is difficult to believe that the sentiments flowing from Fuhrman’s lips were feigned, it does appear that at least some events he told of were invented by him, like the milquetoast accountant fancifully boasting to a bartender of how he had told off the corporation’s chairman of the board.

Here was a member of a pack within the LAPD that called itself “MAW”—standing for “Men Against Women”—who obviously resented being subordinate to a woman. In her book, “Without a Doubt,” Simpson prosecutor Marcia Clark recites:

“Mark had described two run-ins with [York], including one during which she upbraided the squad for writing ‘KKK’ on the calendar entry for Martin Luther King [Jr.] Day. Mark had snickered, and when she called him on it in private, he claimed, he belittled her to her face. In another dustup, he refused an assignment from her, supposedly saying, ‘I don’t talk to anybody that [sic] isn’t a policeman, and you’re as far from a policeman as I’ve seen—and as far as that goes, you’re about as far from a woman as I’ve seen.’ ”

(“Sic” is in the original.”)

If the tapes were to be admitted, York’s testimony could be significant by way of putting Fuhrman’s boasts in perspective.

But should they be admitted? That was the question before Ito. A hearing was held on the morning of Aug. 15. Ito declared that under compulsion of Code of Civil Procedure §170.1(A)(1)—which says that a judge is disqualified if “the spouse of the Judge is to the Judge’s knowledge likely to be a material witness in the proceeding”—he was recusing himself from making the decision as to the admissibility of the tapes.

![]()

But was that enough? Clark recounts in her book that after that morning session….

“Upstairs in the D.A.’s office, anger was building like steam in a presssure cooker. By the time I reached the eighteenth floor, brass and deputies alike were gathered in [DDA] Bill [Hodgman]’s office. They had reached a consensus. We should demand Lance Ito’s full recusal.

“The argument went like this: Even if Lance stepped aside for a ruling on the tapes, he would still be the one to enforce that ruling. But the essential conflict of interest would remain. You’d need two judges on the bench for the rest of the trial. Introducing this unusual set of circumstances would lead the jury to conclude that the Fuhrman tapes were the most important thing in this case.

“The pro-recusal faction was insistent. The two-judge scenario would be a disaster. We had to have one judge—not Lance—for the rest of the the trial.”

Clark discloses that colleagues had drafted a letter for her to sign calling upon Ito to recuse himself. That, she says, would have gone too far. The prosecutor reasons that while a new judge studied to get up to speed on the case, jurors would have to be released from sequestration…meaning that they “would get an earful of any defense propaganda they hadn’t already managed to hear”—and, probably, during the lag, “we’d lose enough jurors to cause a mistrial.” She adds that from Ito’s career standpoint, “it would destroy him.”

The foul-mouthed spitfire tells in her book of what she said to Garcetti et al., before storming out of the room:

“ ‘We’re not doing this,’ I said to Gil and the brass. ‘This letter is not going out over my name. If you don’t want to listen to me, then you f—ing do it.’ ”

At an afternoon session on Aug. 15, Clark announced in open court, viewed by TV-watchers but not jurors:

“We’ve had extensive discussions upstairs, consulted with appellate attorneys and reviewed the case law as well. What I would like leave of the court to do…is to present the court with our written position in the morning. We have to marshal the cases and the factual basis for it. It would appear based on consultation with everyone that the only road to take is to not to waive any matters in this court and to proceed with a complete recusal from this point forward. I would like the opportunity to brief this further.”

She added that she wanted “to make sure of our position.”

![]()

Subsequent to Clark’s bombshell announcement, Garcetti held further discussions in his office. Clark observes: “Now it was if the skies had been sunny all along,” and the resolve to yank Ito off the case had withered.

Although the prosecution clearly had been miffed by some of Ito’s rulings, it would appear that the prevailing sentiment was that, as the adage goes, it’s better to “deal with the devil you know that the devil you don’t know.”

The next morning Clark told the judge:

“Although our review of the case law indicated that we are entitled under the law to seek the course of recusal, we have determined that it is not the only course, and although the law does not expressly provide for a partial waiver of conflict, in consideration of all of the factors, your Honor, we have decided that it would not be the appropriate course in this case. Upon weighing the apparent conflict and the Defense desire to make these tapes the cornerstone of their case, against the ability of this Court to maintain its impartiality in the face of great temptation to do otherwise, we have determined that our faith in this Court’s wisdom and integrity has not been and will not be misplaced.”

Ito ruled that only two snippets from Fuhrman’s discourses would go to the jury, and another judge determined that York’s testimony would not be germane to any issues.

Copyright 2010, Metropolitan News Company