Monday, March 15, 2010

Page 9

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Political Career of Ira K. Reiner Takes a Nosedive

By ROGER M. GRACE

119th in a Series

IRA K. REINER might well have won re-election as Los Angeles County district attorney in 1992, in light of his incumbency and his high name-recognition, had it not been for an April 29, 1992, verdict. The jury decided to acquit (popularly translated to mean the prosecutorial office failed to convict) four police officers who on March 3, 1991, had applied grossly excessive force in subduing a combative drunk-driving arrestee, Rodney King, the beating having been videotaped and widely aired.

King was an African American; sensibilities in the black community had already been roused by the no-prison sentence of Soon Ja Du, a shopkeeper, born in Korea, who had fatally shot a 15-year-old black girl she suspected of shoplifting.

The verdict triggered a riot, one that left 51 persons dead, and massive destruction of property.

Reiner was widely blamed. He should have put King on the stand, it was argued. (The DA answered that the defense lawyers would then have “put the victim on trial”—and, besides, King couldn’t have added anything that wasn’t otherwise shown.) Reiner should have resisted more strongly than he did a transfer of the case to the Simi Valley in Ventura County, after the Court of Appeal ordered a change of venue from Los Angeles County, according to critiques. Simi Valley, the census showed, had an African American population of about 1.5 percent and, as it turned out, there were no blacks on the jury. In light of that, some charged, Reiner blundered in retaining an African American as lead prosecutor.

Too, the loss in the King case, following acquittals in the McMartin Preschool child molestation case and a prosecution that stemmed from deaths on the set of “Twilight Zone—the Movie,” caused voters to wonder if the DA’s Office was capable of winning cases under Reiner.

![]()

The incumbent’s chief opponent was Deputy District Attorney Gil Garcetti, then head deputy in Torrance.

Garcetti had been one of Reiner’s champions in his successful 1984 bid to topple District Attorney Robert H. Philibosian; he was appointed as chief deputy, and ran the office on a day-to-day basis, with Reiner handling the overall decisions and his incessant press conferences; Garcetti was stripped of his top-level post in 1988, and humiliated, working for a time out of a small office afforded him by the county counsel in his own headquarters.

Also in the contest were Deputy District Attorney Sterling Norris (who would run again, without success, in four years), Beverly Hills City Councilman Robert Tanenbaum (an author and former New York prosecutor), and immigration attorney Howard Johnson (who was not a serious candidate).

![]()

In entering the race on Jan. 13, 1992, Garcetti, 50, slammed Reiner, 56, for uttering “shoot-from-the-lip publicity statements that have aggravated racial tensions in our community,” according to a report in the next day’s issue of the MetNews.

The article says that Garcetti declared that he “strongly disagreed” with the probation sentence of Du by then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Joyce Karlin, but decried Reiner’s verbal offensive against the neophyte judge, saying that positive relations with the court should be maintained. According to the account, Garcetti said that if he had been in Reiner’s shoes, he would have tried to work quietly with the presiding judge, Ricardo Torres, and sought Karlin’s reassignment only if a pattern of lenient sentencing emerged.

The news story goes on to report:

“Following Norris’ lead, Garcetti also challenged Reiner for allegedly putting three political aides on the county payroll. Garcetti also mentioned pollster Steve Teichner, former Attorney General John Van de Kamp’s advisor Barbara Johnson, and speech writer Fred Register as political experts posing as prosecutorial employees—an assertion Reiner officials have strongly denied.

“Garcetti said he did not object to the district attorney’s involvement in the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission’s probe of alleged political activity in the office of City Attorney James Hahn. But Garcetti added:

“ ‘Ironically, [Reiner] is investigating the city attorney for the same thing he is doing.’ ”

![]()

Reiner, though a candidate, observed a self-imposed restriction on himself: not commenting on the race until after the March 6 filing deadline. A March 16 profile of Garcetti in the MetNews notes that Reiner “has still not commented on the race at press time.”

The profile quotes Garcetti as slamming the incumbent for having “attempted to contact the judge” in the McMartin case by telephone, on an ex parte basis. It attributes to Garcetti this comment:

“Professionals in the office were embarrassed by that.”

In that interview, as in campaign appearances, Garcetti brought up Reiner’s 1987 portrayal of a Glendale Municipal Court commissioner as a racist for uttering the word “nigger” during a proceeding. The case before the judicial officer, Daniel Calabro, entailed the use of that epithet by the defendant, and Calabro was bemoaning that the term was not yet in disuse.

The article quotes Garcetti as remarking of Reiner’s conduct:

“[B]efore getting all of the facts, he did the same thing he did with Karlin.”

Reiner forbade deputies to stipulate to Calabro, lifting that order after his ploy backfired by engendering criticism, particularly within the legal community. As to Karlin, he announced a blanket affidavit policy in November 1991, but quickly relented, apparently in exchange for a promise by Torres that she would be transferred out of a criminal courtroom. She was shifted to juvenile dependency cases in early 1992.

![]()

Reiner finally responded to criticisms of him by his three major opponents on March 26, taking them on in a debate before the Mexican American Bar Assn.

As to Reiner’s action against Karlin, the Los Angeles Times report quotes Garcetti as terming it “an abuse of power...for political purposes,” while Tanenbaum asserted that the DA had “pandered to the black community,” and Norris asserted there had been “a crucifixion” of the judge.

The article recounts Reiner’s rejoinder:

“No one has ever accused me of keeping my opinions to myself, and I don’t....As the district attorney, I have a duty to speak out for justice and I did....That was an appropriate action.”

In an April 16 debate sponsored by the John M. Langston Bar Assn. and the Black Women Lawyers Assn., Reiner declared:

“Gil has accused me of being political in taking action against Judge Karlin. Well, that was not political; that was simple justice.”

The MetNews’ April 21 issue tells of the reaction to Reiner’s remarks at that Inglewood event by a candidate for Congress, William Fahey, now a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, and then, as now, Karlin’s husband. The article says:

“In a prepared statement, Fahey accused Reiner, by his remarks to the black lawyers group, of ‘seeking once again to inflame the community over the Du sentence,’ and showing that he is ‘not interested in the healing process.’

“He added:

“‘For Ira Reiner, racial tension is a means to an end—his own reelection.’ ”

(My wife and I were scheduled to have dinner with Karlin and Fahey, at the Pacific Dining Car, the following week. I can understand why they cancelled. The night we were planning to meet was April 29…the day the riot started. The restaurant, just west of downtown, is in the area that was part of the riot zone. Aside from that, there had been demonstrations outside the couple’s South Bay home, and the Compton courthouse, where Karlin sat, had at one point been stormed by her detractors.)

Another debate took place May 28. The June 1 issue of the Washington Post reports that Reiner complained of the campaign attacks on him by saying:

“I am accused of everything except having carnal knowledge with a barnyard animal.”

![]()

A theme of the attacks on Reiner was that he was a “politician,” not a trained prosecutor.

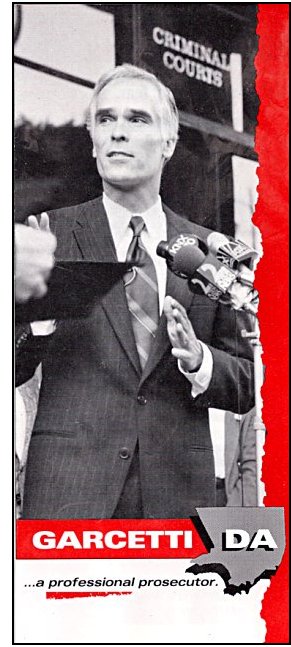

The

pamphlet, at the right, on the cover, calls Garcetti “a professional

prosecutor.” Text on the inside proclaims:

inside proclaims:

“The one person who could provide leadership to make our streets safe again—the District Attorney—is more concerned with his political career than with effectively prosecuting criminals.”

A Norris campaign card describes that candidate as a “real prosecutor—not a politician.”

Aired near the end of the campaign, a Garcetti TV commercial begins:

“Ira Reiner? The politician? For D.A.? No way!”

A Times article on May 31, summing up charges against Reiner says:

“He is a media hound, opponents and other critics complain. He has never tried a felony case, they protest. He is a politician, they say, not a real prosecutor.”

![]()

Except for his statements in the debates, the usually vocal Reiner was little heard from during the primary election campaign. A May 17 article on the race in the New York Times says: “Mr. Reiner did not respond to repeated requests to be interviewed.”

That article declares:

“[W]ounded by his office’s failure to win convictions in the Rodney G. King beating case, Mr. Reiner faces a strong challenge in the election on June 2 and may even lose his post.”

A piece in the Sunday Times on May 31, two days before the election, relates:

“In an interview Thursday, Reiner said the heavy workload he faced during the recent Los Angeles riots has prevented him from vigorously campaigning and raising money. Although he refused to speculate on his political future, he sounded less the brash, confident Reiner of years gone by and more like a man who is preparing himself for the possibility that he might be out of a job.”

![]()

It was Norris who drew the MetNews endorsement, notwithstanding that he was not a major contender. A March 27 editorial says:

“The incumbent, Ira Reiner, is, as we see it, a publicity-thirsty politico who is devoid of administrative capacity, commitment to fair play, or courtroom savvy. Any of his three opponents would be an improvement....

“We endorse Sterling Norris in the belief that he qualifies as the most un-Reinerlike of the candidates.”

A May 26 editorial in the Times also endorses Norris, but is less harsh as to the incumbent. It says of Reiner:

“[T]he truth is that after eight years in office and at least as much controversy as accomplishment to show for his efforts, Dist. Atty. Reiner cannot make an open-and-shut case for his reelection....

“The incumbent D.A. finds himself under the microscope because his office has lost huge cases (Rodney King was but the latest) and because he sometimes tries too hard to lob applause lines to the political bleachers.”

With respect to Norris, it says that “many will want to seriously consider this articulate candidate,” explaining:

“Even those in the L.A. district attorney’s office who very strenuously disagree with Norris’ conservative political views speak admiringly of his competence, professionalism and commitment to aggressive but ethical prosecution.”

With the Herald Examiner having folded three years earlier, and the Daily News (an outgrowth of the Valley News and Green Sheet) backing Tanenbaum, Reiner had a lot riding on a possible endorsement by the Times. Four years earlier, he had gained the Times’ lukewarm support in an editorial that characterized him as “a capable district attorney.” There was no such praise now. Reiner’s credibility was crumbling.

![]()

Garcetti captured 455,788 votes, which was 34 percent of those cast, and Reiner drew 346,590 ballots, or 26 percent.

The remaining votes were divided as follows: Tanenbaum, 254,580, 19 percent; Norris, 182,460, 14 percent; Johnson, 102,652, 8 percent.

Although Garcetti and Reiner each had ammunition in the form of private knowledge of the other’s doings, virtually nothing emerged in campaign oratory during the primary that hadn’t already appeared in the press. That, it appeared, was about to change.

The day after the primary, Reiner spoke of his demotion of Garcetti four years earlier, saying “it was necessary to remove him for very serious personal reasons,” and he vowed to discuss the reasons in the months ahead.

The DA termed his challenger “secretive” and warned that he is “not to be trusted in a position of power.”

For his part, Garcetti boasted that he had “173 spiral notebooks,” in the nature of diaries, chronicling conversations with Reiner while his chief deputy, and actions he took at Reiner’s behest. “I can document a lot more than he can,” a Times article quotes Garcetti as saying.

One has to wonder whether the content of those notebooks had anything to do with Reiner’s ultimate decision to quit the race.

Copyright 2010, Metropolitan News Company