Thursday, November 19, 2009

Page 11

REMINISCING (Column)

Hatch Forms Law Partnership With Brown, Miller

By ROGER M. GRACE

DAVID PATTERSON HATCH, a former judge of the Santa Barbara Superior Court, took on a couple of law partners shortly before his move into the new Wilcox Building in 1896. The partnership would be short-lived.

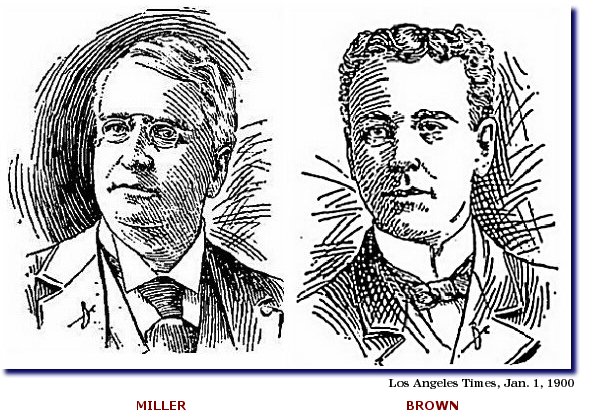

JOHN M. MILLER was one of the partners. He had only recently moved to Los Angeles.

Miller was commonly referred to as “Judge Miller,” though he had never held a judgeship. (See “Reminiscing,” Jan. 8.)

Born in Pennsylvania, he began law practice there in 1870 at the age of 23, then moved to Minnesota where he practiced for 15 years, the last 11 of those years being largely devoted to representation of three Minneapolis newspapers. He relocated here because of his wife’s ill health, having been lured, as many had been and would be, by tales of California’s salubrious clime.

HERBERT CUTLER BROWN had in common with Miller a background of employment by newspapers—though his experience was in the journalistic end. After graduating from college, he worked on dailies in his native Chicago—and in 1886, at age 21, published his own weekly newspaper. He was admitted to practice in California in 1893.

He was the junior partner in the new firm.

One of the first cases in which Hatch, Miller & Brown provided services was a divorce action brought by one Maria Amparo Ballerino against her husband, Bartolo Ballerino. The services were engaged by attorney J. Marion Brooks, who needed help in the case. The firm provided those services between March 25, 1896 and June 1, 1897.

On May 26, 1896, only two months after the law firm entered the case, Maria Ballerino’s action for a divorce failed, with a finding that her husband had not committed adultery—or “marital infelicity” as it was then euphemistically termed. Ensuing hassles were over property matters. Bartolo Ballerino wound up agreeing to deed half of the community property to his wife in exchange for her agreement not to appeal the judgment in the divorce action.

Hatch, Miller & Brown presented its bill for legal services to Maria Ballerino; she wouldn’t pay it, assertting that Brooks had told her he would have the lawyers assist him at his own expense. The client did not, at the time the assurance was made—assuming it was made—insist that it be put in writing. That was not surprising given that she was illiterate and unsophisticated in business matters.

The law firm assigned its claim to Miller, and he brought suit in Los Angeles Superior Court against Maria Ballerino on June 3, 1897. (Brooks’ assignee filed a complaint on March 18, 1897, for the unpaid $500 balance on the $7,000 fee Brooks charged her, pursuant to a written contract.)

On the face of it, it might seem incredible that someone of Brooks’ stature would lower himself to taking advantage of an ignorant and vulnerable client. He had been a U.S. attorney for the Southern District of California, a state senator, an assemblyman. On the other hand, steady employment was behind him. In 1901, his law office address was also the address of an obscure law school, suggesting he was supplementing his income by coaching would-be lawyers for the oral bar examination. (This is discussed in “Perspectives,” Aug. 26, 2009.) In 1908, a judge refused to allow Brooks to represent a client in his courtroom, discerning that he was drunk. (Brooks then sued the judge for $25,000 for slandering him.)

Back to 1897. Miller had sought $2,500 from Maria Ballerino, as the reasonable value of the firm’s services. San Bernardino Superior Court Judge John L. Campbell, sitting as a judge of the Superior Court here, awarded $1,000.

The California Supreme Court affirmed, on Feb. 24, 1902. Next week, I’ll discuss the opinion in the case.

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company