Wednesday, December 30, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

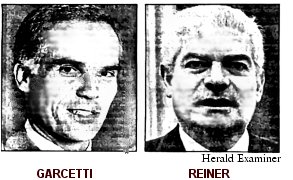

Uncertainty Remains Over Why Reiner Demoted Garcetti (Then Hiked His Pay)

By ROGER M. GRACE

115th in a Series

IRA K. REINER’s September, 1988 demotion of Gil Garcetti from his post as chief deputy, the Number Two spot in the office, and his actions which followed, remain bewildering to this day.

It was announced by the DA’s Office on Sept. 14 that effective Oct. 3, Garcetti would become head of the office in Santa Monica. But a dejected Garcetti grumbled, for the record, that he might resign.

An indication that a resignation by him was anticipated by Reiner was that the current head of the Santa Monica branch had not contemporaneously been notified of an impending transfer. In an interview published in the Los Angeles Times on Sept. 16, 1990, Garcetti is quoted as reflecting that Reiner had expected him to quit.

As noted here yesterday, Garcetti did not wind up going to Santa Monica.

A Page One article in the Daily News on April 23, 1989, reveals:

“Gilbert Garcetti, dumped in September as District Attorney Ira Reiner’s chief aide, still draws the $121,308 salary and perks of the county’s No. 2 prosecutor although he spends his days doing routine paperwork in a small room at the County Counsel’s Office, the Daily News has learned.

“Garcetti holds the title of a head deputy district attorney—a grade reserved for supervisors of entire divisions or branch offices—but his primary assignment involves reviewing a handful of minor lawsuits and developing an affirmative action program for the department.

“ ‘There is nothing at all inappropriate about where I’m working or what I’m doing,’ said Garcetti, 47.

“ ‘Anyone who knows anything about the District Attorney’s Office knows that, from time to time, a head deputy can be assigned outside the regular duties on special projects,’ he said. ‘I’m doing this out of my own choosing, not because of some deal.’ ”

Reiner is quoted as saying that it was arranged for Garcetti to remain downtown after he said he would quit rather than go to Santa Monica.

The Daily News article states that Garcetti explained his presence in the county counsel’s office, located in the Hall of Administration, by saying that (aside from space in the Criminal Courts Building being cramped) that it would be “uncomfortable” for him, Reiner and Thompson if he were there.

The article notes:

“In addition to retaining his salary as a head deputy district attorney, Garcetti also has retained use of a county vehicle—a benefit typically reserved for the county’s top managers.”

Why was Reiner desirous of keeping Garcetti in the office, notwithstanding tension between them? And why was he making accommodations? Was it a matter of loyalty to an early political supporter? Or was it out of fear of the contents of the 173 spiral notebooks in which Garcetti had memorialized their conversations and other happenings during Reiner’s first term?

The existence of those notebooks was revealed by Garcetti at a June 3, 1992 press conference, the day after the primary election in which he led a field of five candidates for the DA’s post, with Reiner coming in second.

Neither Reiner nor Garcetti is willing to be interviewed.

![]()

The Daily News article, written by then-staff writer Tom Chorneau, appeared on a Sunday. The next day, Garcetti learned he would now be heading a new hiring and training division, and would report to Assistant District Attorney Curt Livesay, according to an April 25 article by Chorneau. Garcetti was advised of the new post in a memo that bore the previous Wednesday’s date, the report notes.

While Livesay is attributed with a statement that Garcetti’s duties would be expanded, the ousted chief deputy contradicted that. He would continue to work out of the county counsel’s office and, he’s quoted as saying, “[M]y duties will remain the same. I will continue to work on the affirmative-action program and the lawsuits and when I am finished with those projects, I will leave the office.”

The newspaper dug deeper. In its issue of April 28, Chorneau reports that Garcetti “has received 18 hours of overtime compensation since being reassigned in September, records obtained Thursday show.”

The article goes on to say that, in the words of county Chief Administrative Officer Richard Dixon:

“It is general county policy that top management personnel do not receive overtime pay.”

Garcetti disclosed that he planned to leave county employment at the end of the summer, Chorneau relates. (As it turned out, he stayed on, and was put in charge of the Torrance branch in 1990.)

The reporter uncovered more. His story on May 13 says:

“Los Angeles County District Attorney Ira Reiner approved $30,544 in overtime pay for his ousted chief deputy, Gilbert Garcetti, and his former chief fiscal officer, Nancy Morton, during 1987 and 1988, documents obtained Friday show.

“Responding to a request made under the California [Public] Records Act, officials at the District Attorney’s Office confirmed that the overtime was granted by Reiner during a time that Garcetti was denying requests for similar compensation from trial attorneys and other top managers.

“Reiner

said in an interview that he did not know Garcetti was denying overtime to

others while getting Reiner to approve his own.

“Reiner

said in an interview that he did not know Garcetti was denying overtime to

others while getting Reiner to approve his own.

“ ‘Apparently he didn’t apply the policy equitably,’ Reiner said. ‘Because of the needs of the office, he didn’t take the (compensatory time) off and asked to be paid. The problem was that there were others with an equal situation and he didn’t authorize the pay for them. It wasn’t equitable.’ ”

You’ll notice that Reiner was not accepting any of the blame, personally. The buck never stopped at his desk.

The article makes note:

“Morton, who was replaced in October and now works as an assistant treasurer and tax collector, was out of town. While at the District Attorney’s Office, Morton earned a top salary of $80,391.”

Is it coincidental that Morton left the DA’s Office right about the time that Garcetti lost his post as chief deputy? While Reiner admittedly knew about the overtime, he apparently did not know that Garcetti and his friend Morton were the only ones in the office receiving it. Did a sudden realization of this account for the job actions?

![]()

The same day that piece appeared, the Herald Examiner also reported on the overtime payments to Garcetti, as well as to Morton, described as Garcetti’s “close ally and confidante.”

The article, by staff writer Nancy Hill-Holtzman, quotes Garcetti as saying:

“I didn’t approve any overtime for myself. [Reiner] approved it and I accepted it. There is no question I earned it.”

The report continues:

“For instance, on Jan. 1, 1987, Garcetti asked to be paid for 134 hours in excess of the 144-hour maximum in compensatory time off that can be carried from year to year, according to…documents.

“Garcetti said the 134 hours were all worked on weekends and holidays, because top managers did not turn in claims for overtime hours during the normal work week.

“‘I can tell you I gave my heart and soul to my office and the district attorney while I was chief deputy, sometimes to the detriment of my family, for nearly four years.’”

Note to Barack Obama, Ronald George, Steve Cooley: you might have a claim for overtime pay for services rendered on weekends or holidays.

“Meanwhile, Deputy District Attorney Larry Longo, in a murder trial for 15 months and unable to take time off, said he lost 350 hours of compensatory time off at the end of the year,” the Herald Examiner article says.

“Longo said he was told by Garcetti he could not carryover the time, his first choice, nor could he be paid for it. ‘When I went in and I asked Garcetti for the overtime, he told me, we’re professionals and sometimes we have to eat the overtime.

“‘I was really shocked when he gave it to himself,’ Longo said. ‘I really think Garcetti pulled the strings on this one.’”

Retired Deputy District Attorney Lea D’Agostino tells me that she “never thought” of putting in for overtime in 1987 when she prosecuted the manslaughter case against five defendants accused of causing deaths on the set of “Twiglight Zone—the Movie.” She says she worked seven days a week for 10 months, taking only a half-day off in April for her birthday celebration.

![]()

The various Daily News stories mention that Garcetti, after being demoted, was allowed to hold onto his $121,308 annual salary. The Herald Examiner reports set the figure at $8.04 higher…hardly a meaningful discrepancy.

But what the Her-Ex uncovered was that as of the moment Garcetti was stripped of his rank, he had been making less than either figure.

A May 30 article by Hill-Holtzman begins:

“Two weeks after demoting him last fall, Los Angeles District Attorney Ira Reiner approved a 7.5 percent ‘golden parachute’ pay raise for his former top lieutenant, Gilbert Garcetti, under the county’s ‘pay for performance’ plan to reward good managers.…

“His pay increase, signed Sept. 30, 1988, and backdated to the beginning of the month, brought Garcetti’s salary to $121,316.04 a year, in the upper reaches of the county pay scale.

“Garcetti earns $11,000 more than his replacement, according to pay records obtained under the California Public Records Act.

“ ‘Gil was a very hard worker,’ Reiner explained Friday. ‘I thought it was appropriate not to deny him a raise he was previously scheduled to get.’

“Garcetti explains the raise differently, saying he personally requested the increase to enhance his worth in the private sector as he searched for a new job outside the county.”

![]()

The reason for the demotion has never come out. Garcetti is quoted in the Sept. 16, 1990 Times article as saying:

“When [Reiner] dropped the bombshell on me, I, of course, asked whether my performance had been unsatisfactory in some way. I remember him holding up his hand, like, ‘Stop,’ and he said it wouldn’t pay to discuss it. He simply wanted Greg Thompson to be his chief deputy.”

A Sept. 19, 1992 report in the New York Times of Reiner’s withdrawal from the DA’s contest includes this:

“Mr. Reiner has said that Mr. Garcetti ‘is not to be trusted in a position of power’ and hinted that he would make public previously undisclosed reasons for his demotion.”

He didn’t. The closest Reiner has come to stating his reasons, so far as I can tell, is a post-primary comment to the Times, published June 4, 1992, that “it was necessary to remove [Garcetti] for very serious personal reasons.”

![]()

POSTSCRIPT: Even after the press reports of Garcetti, while chief deputy, attaining overtime payments while other prosecutors were denied them, the discriminatory practice persisted. In February, 1990, the Daily News obtained documents pursuant to the Public Records Act showing that Thompson had accrued 49 days of overtime pay in 1989.

A March 3, 1990 Daily News article by Dawn Webber says:

A committee of trial deputies and managers in the District Attorney’s Office on Friday completed a working draft of a new overtime policy aimed at ensuring fairness, officials said.

The committee, meeting for the second time, was formed after the Daily News reported last month that highly paid managers routinely claim compensatory time off for overtime while trial deputies are discouraged from taking time off.

Veteran prosecutors expressed anger and disbelief when they learned that well-paid managers earned overtime at all. Many said the general perception among trial deputies had been that managers were not allowed to claim overtime.

Gregory Thompson, top aide to District Attorney Ira Reiner, had called for formation of the committee to formalize a fair, office-wide policy on overtime.

Thompson, who is paid $120,873 a year, claims a day off in overtime every week, while prosecutors in major cases either are discouraged from requesting compensatory time or cannot use their overtime within the two year deadline.

Thompson accrued 329 hours, or 49 days, of overtime during 1989—which is nearly as much as the lead prosecutor in the marathon McMartin Pre-School molestation case claimed over three years.

Thompson actually took 16 days off in compensatory time last year, according to records obtained by the Daily News under the California Public Records Act.

Thompson later served as chief deputy district attorney in Sacramento, then as assistant district attorney in San Diego. Since 2003, he has been director of forensic services for the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department. He could not be reached for comment.

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company