Tuesday, December 8, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

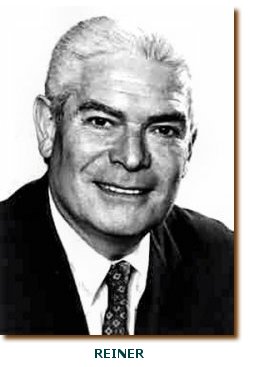

Reiner Grants Extradition Request, Drops Charges Against Five in McMartin Case

By ROGER M. GRACE

108th in a Series

IRA K. REINER was a busy hombre in 1986. For the Los Angeles County district attorney, the relative quietude that existed during his first 13 months in office was over.

In January of 1986, alone, there were these developments:

•Jan. 15: Reiner announced that two men charged here with the murder of a Domino Pizza deliveryman a month earlier would be extradited to South Carolina to face murder charges there. However, the Governor’s Office, which has the say over extraditions, declared, in effect: “Ahem! Maybe not. We haven’t decided yet.” Gov. George Deukmejian later said “no.”

•Jan. 17: Reiner dropped all charges against five of the seven defendants charged with child molestation at the McMartin Pre-School. Evidence against the five was “incredibly weak,” he proclaimed, spawning questions as to why, if that were so, the charges, preferred even before he took office in December 1984, had not been dismissed sooner. Or was it so that the charges were not sustainable?

•Jan. 24: An indictment was unsealed charging U.S. Rep. Bobbi Fiedler, R-Chatsworth, with feloniously seeking to buy-off a competitor in the race for the U.S. Senate with a $100,000 payment. Although Reiner had only sought an indictment of Fiedler’s chief aide, it was made clear after the indictment that his office would prosecute her, as well as him. Reiner went off on vacation in Europe three days later and failed to make any contact with his office while away; when he got back 18 days hence, editorial criticism of the prosecution had arisen; he dropped the prosecution of Fiedler and publicly disavowed statements made in his absence by his chief deputy, Gil Garcetti.

Later in 1986:

•Oct. 13: the State Bar of California announced it would publicly reprove Reiner in connection with violations of ethics rules while Los Angeles city attorney. (The order was entered Oct. 17.)

•Nov. 4: Comments by Reiner were aired on a “60 Minutes”

segment dealing with the McMartin case. In the course of rationalizing his

decision to drop charges against five of the defendants, he proclaimed that the

prosecution was precipitously launched by his predecessor and blown “massively

out of proportion” to the actual misdeeds at the school. Reiner was seen by

many as having jeopardized chances of convicting the two remaining defendants

by creating negativity toward the prosecution.

Domino’s Pizza Slayings occurred in South Carolina on Dec. 3, 1985. Mitchell Carlton Sims and Ruby Padgett were sought in connection with the murder of two Domino’s Pizza employees during an armed robbery. They were here for the Glendale murder on Dec. 10 of a deliveryman for that company, whom they drowned in the bathtub of a motel room they occupied. (Sims was a disgruntled former employee of Domino’s.)

Apprehended on Christmas day in Las Vegas, Sims and Padgett were turned over to Los Angeles County authorities, and a prosecution commenced.

The governor of South Carolina wanted to have the pair tried in his state, first. An Associated Press story , datelined Columbia, S.C., says that Gov. Dick Riley “called the governor of California Tuesday,” Dec. 31, 1985, asking that the suspects be extradited to his state.

Reiner got in the act. He figured that extradition would be a good idea since it appeared that a trial there would take only about six months, while proceedings here might stretch over two or three years.

The DA wrote to Riley saying, as quoted in the Jan. 16 issue of the Times:

“I believe that the interests of justice would be served if these defendants are held accountable in a manner that is both timely and appropriate. Therefore, although this action is unprecedented, I am pleased to honor your request….”

A spokesman for Deukmejian is quoted in the Times article as responding:

“[I]t is crystal clear to us that governors make decisions regarding extraditions, and not district attorneys.”

On Feb. 4, Deukmejian announced he was denying the extradition request because he did not want the evidence here to get stale. A United Press International dispatch reports Reiner’s reaction that he was “dumbfounded” by the governor’s action.

![]()

In a syndicated column appearing in numerous California newspapers, Thomas Elias took Reiner’s part. His March 26 column recites that Reiner “decided that there was a far greater chance that the two alleged killers would be executed if convicted in South Carolina than if they stood trial here first.”

There would have been somewhat of a problem with executing Ruby Padgett in South Carolina, even if convicted. She wasn’t charged with a capital crime. She was viewed as an accessory after the fact.

Anyway, the column continues:

Anyway, the column continues:

“The governor has never liked Reiner, especially since Reiner ousted Robert Philobosian, a Deukmejian pal and former assistant, from the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office in the 1984 election. Here was a chance to put Reiner in his place.

“Deukmejian immediately leaped onto the well-publicized case, noting first that extradition decisions belong to the governor, not local prosecutors. Never mind that requests of local prosecutors are almost always given routine approval.”

Even if such recommendations were routinely adopted by governors, does it not still appear a bit brash for a DA to merely presume that his advice would be taken, and to announce to a governor of another state that “I am pleased to honor your request,” as if the DA were possessed of final decision-making authority?

Elias’ column quotes Garcetti as saying that Deukmejian’s decision “greatly impedes our chances of successfully obtaining a death penalty” verdict in the Los Angeles case because if there were a prior conviction in South Carolina, it could be used at the penalty phrase.

The column asserts:

“The upshot is that death penalty advocate Deukmejian has single-handedly reduced the chances that the Domino suspects will ever be executed, either here or in South Carolina.

“He doesn’t admit it, but it’s virtually certain his grudge against Reiner, who defeated one of his closest allies, was the key reason.”

What Elias is “virtually certain” of strikes me as being long on supposition and short on facts. While I wouldn’t doubt that Deukmejian “never liked Reiner” and was disappointed over Philibosian’s 1984 loss, those factors, alone, hardly justify a conclusion that the governor, a former attorney general, made his call on a prosecutorial issue based on spite.

Moreover, despite the implication of Elias’s column—and Reiner’s express characterization of Deukmejian’s action, quoted in the March 2 edition of the Daily News, as “so petty”—I have not, through the years, discerned a trace of pettiness on Deukmejian’s part. Have you?

![]()

Deukmejian’s action did not impede the reaching of a death verdict. Sims and Padgett were convicted in Los Angeles Superior Court, and Sims was sentenced to death. His accomplice was given a life sentence, without possibility of parole.

The California Supreme Court affirmed the death sentence in a 6-1 opinion on June 28, 1993. The latest news, as reported in the MetNews on Sept. 22, 2005, is that the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals the previous day denied Sims’ petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

An Associated Press dispatch from Charleston reports that Sims was

returned to South

Carolina

on Aug. 12,

1988, to

face trial there. The Aiken (South Carolina) Standard’s issue of May 12, 1989, tells of a verdict of

guilty the previous day on both murder counts, and a count of armed robbery.

The South Carolina Supreme Court affirmed a death sentence in 1991.

McMartin Pre-School Child Molestation charges had long been pending against the five persons whom Reiner decided to let off the hook. His decision was—of course—announced at press conference.

A Jan. 24, 1986 editorial in the Los Angeles Times observes:

Either guilty people are being let off or innocent people have been unjustly and irreparably harmed. Children have been interviewed, have testified and been cross-examined and buffeted by the legal system—to what end? The remaining cases against two defendants [Peggy McMartin Buckey and her son, Raymond Buckey] and rely on the same testimony of the same witnesses. How strong can they be? Has a message gone out to child molesters that the difficulties of prosecuting them mean that they need not fear prosecution?

No matter what explanation is given, it strains credulity that Dist. Atty. Ira Reiner could not have reached his decision to drop charges sooner. It is quite likely that Reiner believes that the initial charges were blown out of proportion and that much less child molesting took place at the McMartin Preschool than the public has come to believe. Why did it take two district attorneys nearly two years to discover this?

It would be easy to blame Robert H. Philibosian, Reiner’s predecessor. He was the district attorney in 1984, when the case got under way. Facing an election, this theory goes, he rushed to file charges in a high-visibility case even though his investigation was far from complete.

But blaming Philibosian overlooks the fact that a grand jury examined the evidence and returned indictments. A week before Reiner dropped the charges, his prosecutor in the courtroom asked a municipal judge, Aviva K. Bobb, to hold all defendants on all counts, and Bobb, having heard the evidence, ordered them to trial. These peoples’ actions support Philibosian’s original decision to file charges. What made Reiner change his mind and drop the cases?

In her Jan. 24 Herald Examiner column, editor Mary Anne Dolan puts it quite ably:

Ira Reiner took office on Dec. 3, 1984. From the moment he was sworn in, it was his duty to review and evaluate all cases being handled by the district attorney’s office.

At any point Reiner could have interrupted the McMartin proceedings to revise or dismiss charges.

The preliminary hearing opened on Aug. 17, 1984, an appropriate time to control the chaos before it began. June of 1985, when the prosecution rested its case, was another fine time to step in, as Municipal Judge Aviva Bobb pointed out this week.

Instead, the dashing DA grabbed spotlight after spotlight with other cases. He made pronouncements about keeping the courts open on Saturdays and devised dramatic schemes to identify prostitutes’ johns [by publicly releasing their names] and snare deadbeat dads [by rounding them up].

While the McMartin sores festered, Reiner went merrily on his way, never missing the opportunity to make a political endorsement and keeping every appointment in the back rooms of City Hall pols.

He found the time to make network news pronouncements about Marilyn Monroe [terming the Grand Jury’s call for a new investigation into the actress’s 1962 death “irresponsible almost beyond description”] and turned all questions regarding McMartin, the largest and most sensitive court case in recent L.A. history, over to Deputy District Attorney Gilbert Garcetti.

For 17 months, while court costs for the preliminary hearing mounted to $4 million, Ira Reiner hung back.

He allowed, indeed tacitly encouraged, the very circuslike atmosphere which he later denounced as “hysteria.”

He waited while child after child was forced to repeat, in stomach-turning detail, what were either terrifying facts or equally horrifying nightmares.

Finally, he chose his moment on stage with the shrewdness of a Spencer Tracy in “The Last Hurrah.” It was the instant of peak potential for emotional response all around, the point where he could attempt to come off as judicious (I could have done this earlier), and brave (I could have let this go even further) and, most especially, as a political hero (my predecessor, Robert Philibosian’s to blame).

On such an occasion, one couldn’t help but ask even so bold a pol: Did you think you were being fair?

“No. I don’t think anyone should be proud of the system as it operated here,” he replied.

The system in this case was in no one’s hands but Ira Reiner’s. His is, after all, the largest and arguably the most powerful prosecutorial office in the land.

Fortunately, Ira Reiner can be turned out of that office by voters.

All of those offended by his mockery of justice in this instance—the McMartin parents, the tarnished defendants, the many citizens who right now are too stunned and sick of it all to react—will vote to send him packing.

Reiner was not turned out of office at the next election, which occurred in 1988. That election will be dealt with in a future column. Also to be discussed will be the 1986 events only touched upon above: the prosecution of Fiedler (the topic of a column tomorrow), the public reproval of Reiner by the State Bar, the DA’s comments on “60 Minutes.” There will recitations of Reiner’s denunciation of a court commissioner in 1987 for supposed racism, his ill-fated bid for the Democratic nomination for state attorney general in 1990, and his concession of the Office of DA to his 1992 challenger, Gil Garcetti…and more.

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company