Monday, November 23, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

A Tale of Two DAs: Reiner Snubs Allred, Philibosian Lends Aid to Her Effort

By ROGER M. GRACE

106th in a Series

ROBERT H. PHILIBOSIAN succeeded in persuading a prominent feminist/activist to end her sit-in at the offices of the Los Angeles County district attorney. The unusual aspect is that when he did that, in 1985, he was no longer DA.

The incident tells much about Philibosian, and much about his successor.

The protester was Gloria Allred, a liberal with a craving for publicity, who was prone to engage (in those days of her youth) in bizarre stunts to attain attention. Her stunts included hanging diapers in the Los Angeles office of then-Gov. Jerry Brown. Brown was at the time contemplating a veto of a bill that would enable a custodial parent to obtain an assignment of wages of a former spouse who was in arrears in child support payments. (Brown signed the bill.)

Allred was, as I noted recently, a contrast to Philibosian, a staid conservative. Yet, the two had been united in a goal while Philibosian was DA: getting deadbeat parents to pay court-ordered child support.

IRA K. REINER was the new DA. As Allred relates it, she was present at a 1984 reception also attended by Reiner, at a time when he was a candidate for DA; she told him that if he were elected, she would want to talk with him about enforcement of child-support orders; he said he’d be willing to confer. He was elected. She made an appointment to see him on Wednesday, March 13, 1985.

Allred, consistent with her quest for news media attention, alerted the press to her forthcoming meeting, pledging to provide comments afterward. As she now acknowledges, it just might be that the meeting would have occurred had it not been for that tip-off to the press.

Allred showed up for the meeting, along with a few mothers whose ex-spouses were in arrears in child-support payments. She recounts that Reiner’s secretary said of the DA:

“Well, he’s not here.”

The lawyer tried to make another appointment. She says she was told: “He’s not going to be able to meet with you.” Period.

She spoke with an aide—but that wasn’t good enough. Allred said she would wait there until Reiner was available.

Reiner spokesperson Schuyler Sprowles is quoted in a United Press International dispatch as saying:

“He will not be meeting with her today. That’s one thing she can bank on. He’s got real work to do.”

Allred had a proposal to present to Reiner for a program aimed at raking in child support payments from delinquent parents (a program that, after being implemented in other counties, would soon earn her a presidential commendation). But apparently, to Reiner, lending attention to the crisis of parental nonsupport of offspring—with custodial spouses often being forced to go on welfare—was not “real work.”

![]()

At some point that day, Allred was told the building was going to be closed, and if she didn’t leave, she’d be locked in. She wouldn’t leave, and spent the night in the press room.

Should we pity her for her discomfiture? No. She got what she wanted: publicity.

That was something both she and Reiner had a hunger for...the difference being that Allred sought to publicize social causes, as well as herself, while Reiner only wanted to publicize his one cause: Reiner.

Allred recounts that a telephone call came in the middle of the night from a reporter at KFWB, an all-news station, wanting to ascertain if she were still there.

All day the following day, Allred waited to see Reiner. A few mothers waited with her. So did reporters. Reiner would not grant an audience.

At about 6:05 p.m. on that Thursday, she and the other protesters were forcibly ejected from the Criminal Courts Building (then so denominated, now the “Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center”).

![]()

Dennis McCarthy’s column in the Daily News the next day observes:

“For a guy who’s supposed to be smart, Reiner did a stupid thing this week. He ignored Gloria Allred. Then he kicked her out of his office. The gutters of L.A. are strewn with bigwigs who tried the same thing.”

McCarthy goes on to say:

“When Allred showed up at his office to discuss a more effective method of collecting court-ordered child support, the DA should have made time.

“But instead he said he was too busy. He had to go out and make a political endorsement—Lisa Specht for city attorney. That didn’t sit too well with divorced mothers waiting for support checks that never arrive....”

He notes her overnight stay at the CCB and says:

“I stopped by Thursday morning see how she was holding up after spending the night on the press room couch. Not bad, Allred looks like she just stepped out of Christina Ferrare’s bedroom closet.

“Not a hair out of place, not an inch of face without fresh makeup—which is something considering the state of the Criminal Court Building restrooms. I wouldn’t put my briefcase down in these places.”

Allred had the dress she “tried to sleep in,” which was wrinkled, in a grocery bag.

McCarthy quotes her as saying, with respect to Reiner: “I’ll stay until he stops turning his back on women and children.”

![]()

Though ejected Thursday night, Allred was back Friday morning. That’s when Philibosian made contact with her by telephone.

The former DA listened to her plan, while the current DA wouldn’t.

What she proposed had been tried elsewhere, but not here. Every “deadbeat dad” (or mother behind in child support payments) was subject to criminal charges. The plan was to declare amnesty; a parent who was in arrears could come forward, without fear of prosecution, if he or she embarked on a payment plan to catch up on what was owed.

Allred relates that Philibosian “said it was a good idea.”

She says the former DA asked if she would give up her sit-in if he arranged a meeting for her with the state’s acting secretary of health and welfare, James Stockdale. She assented.

“I didn’t want to see her sit there for days on end,” Philibosian reflects.

He says Reiner was not about to budge and there were approaches that might be more productive.

On Monday, Allred held a press conference, at which Philibosian was present.

The next morning’s issue of the Los Angeles Times quotes him as saying:

“Any district attorney should welcome Gloria Allred and these mothers as allies in the war to collect child support.”

Sprowles told the Times reporter:

“If she thinks that conducting a publicity stunt...will somehow get her a meeting with Mr. Reiner, she has another think coming. When you have a woman who comes in here demanding a meeting with you, always with the news media at her side, it doesn’t strike anyone as being sincere.”

Allred insists that when she came on Wednesday of the previous week, on the 13th, she had an appointment.

Later on Monday, the 18th, she flew to Sacramento and met for about two hours with Stockdale.

Afterward, Stockdale told reporters that the Department of Social Services would be contacting district attorneys of the state and urging that consideration be lent to instituting amnesty programs or any other means of causing support obligations to be met.

Five DAs in the state announced such programs in short order. Eventually, the number climbed to 11.

![]()

Reiner would not try it out. Perhaps if Allred had whispered the idea in his ear and he had announced the approach at a press conference, taking the credit for it, such a program would have been instituted here. But Allred was not accustomed to whispering, and Reiner was not one to share credit.

Reiner adopted an alternative approach: have arrests made, and make a lot of noise about it.

A June 10, 1985 article in the Daily News bears the headline, “Armed police to hunt delinquent fathers.” It says:

“Starting at 6 a.m., 42 armed investigators equipped with bullet-proof vests and portable radios will begin ringing the doorbells of the 450 fathers for whom criminal charges have been filed and arrest warrants issued.”

About 24,000 others were to receive letters threatening:

“In order for you to avoid criminal and/or civil prosecution, you must contact this office prior to our instituting any action and/or having a warrant issued for your arrest.”

Being behind in child support payments in the amount of $500 or more was a misdemeanor.

A crackdown on delinquent parents had occurred for some years around Father’s Day, but this year’s effort was to be intensified.

“This is not amnesty,” Reiner is quoted by the Daily News as saying, distancing himself from Allred’s proposal. He said parents “can either come in and make arrangements for payment or they can try to skulk around corners and take the chance of getting caught.”

![]()

On June 13, Orange became the sixth county to announce an amnesty program. Parents behind in support payments would have until Aug. 16 to pay up—otherwise, they’d be prosecuted. State officials gave Allred and Philibosian credit for the program.

A June 16 editorial in the Times says that Reiner “demonstrated an increased commitment to enforcing the child support law” through his “Father’s Day roundup,” but notes that he “has rejected the amnesty plan.” The newspaper comments:

“He maintains that an amnesty program is ‘impracticable’ in his county, but district attorneys in six other large counties had no problems creating an amnesty period at the state’s request. If the trial amnesty program works, Reiner should reconsider his position.”

By mid-afternoon on June 16, 239 arrests had been made.

Reiner’s effort succeeded. So did the amnesty approach.

A July 26, 1985 article in the Times reveals that in June, there was a $2.2 million increase in payment of child support by delinquent parents over the previous year. In the smaller counties of Orange, Riverside, Kern, Santa Cruz, Sacramento and Ventura—where an amnesty program was in effect—the boost in payments amounted to $1.2 million, so far. A Sept. 19 article provides an update: the amount collected through Aug. 16, the deadline, was nearly $2 million.

![]()

On March 10, 1986—three days short of a year since Allred first camped out in Reiner’s waiting room, the feisty lawyer was back, with 11 supporters, all mothers who wanted child support checks.

This time, Allred didn’t have an appointment, but demanded to see Reiner. The women, surely knowing the DA would not meet with them, staged a sit-in.

While it was in progress, Reiner’s office

distributed a press release. As recited in the Daily News the next day:

While it was in progress, Reiner’s office

distributed a press release. As recited in the Daily News the next day:

“A 10-day sweep from Feb. 27 to March 8 netted 287 arrests, and more than 66 more parents surrendered after the district attorney’s Bureau of Family Support Operations dispatched 16 pairs of investigators to enforce arrest warrants, the release said.”

After the protesters idly spent more than five hours in the waiting room, security personnel escorted them out of the building.

![]()

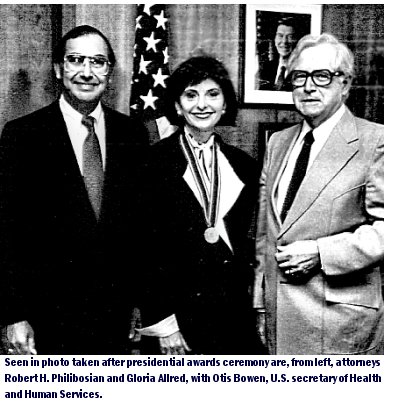

Reiner didn’t like the amnesty plan. The president of the United States, Ronald Reagan, did. Allred was one of 19 recipients of the Presidential Volunteer Awards presented by Reagan at the White House on June 2, 1986.

“Years later,” Allred says in her book “Fight Back and Win,” “Ira Reiner and I agreed to meet—not in his office, but in a coffee shop on Sunset Boulevard—to see if we could resolve our differences. He ended up appointing me co-chair of his child support enforcement committee for Los Angeles County, and soon the amnesty program was successfully instituted there as well.”

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company