Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Philibosian Removes Office ‘Bug,’ Targets ‘Delinquent Dads,’ Protects Police Horses

Trutanich Hails Him as ‘the Quintessential DA’

By ROGER M. GRACE

100th in a Series

ROBERT H. PHILIBOSIAN, as one of his first acts as district attorney, had a “bug”—the electronic sort—removed from the DA’s executive office.

The existence of such a device brings to mind the surreptitious audio recordings of conversations in the Oval Office of the White House, on orders of President Richard Nixon.

Philibosian says that when he walked through the executive office after he was appointed at the end of 1982, he asked Clayton Anderson, chief of the Bureau of Investigation: “Is this office bugged?” He recites that Anderson responded: “Yes it is,” and pointed to an electrical outlet.

The former district attorney says he told Anderson:

“I want it out of here now.”

Philibosian was appointed by the Board of Supervisors to fill the vacancy created by the resignation of John Van de Kamp, who had been elected state attorney general. Van de Kamp tells me that he can state “categorically” that he never authorized installation of electronic surveillance equipment in his office.

“It was never anything that I ever put in or knew about,” he declares.

There are a lot of liars among current and past politicians. Van de Kamp isn’t among them. Nor is Philibosian.

The question remains: who did cause the bugging? And who was listening in? Did this practice of recording go back to the days of Van de Kamp’s predecessor, the late Joe Busch?

The executive office is on the 18th floor of the Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center. Bugs could not have been installed there any earlier than Busch’s regime. Busch and his troops moved into that structure, then the New Criminal Courts Building, when it opened in 1972.

I’ve heard, second-hand, that a retired DA’s investigator postulates that the apparatus had to have been installed when the building was constructed because there was hard-wiring of an electronic system. Certain other rooms, such as interrogation rooms, were also bugged, with the equipment being turned on when the order was given, I’m told.

![]()

In the early days, going back to 1850 and for decades beyond, the post of district attorney was a part-time job, with the DA personally handling every felony trial. As the county grew, so did the office—yet each DA made at least one court appearance in his capacity as DA…ending with Philibosian.

That district attorney appeared in court on Jan. 9, 1984, at the sentencing of Hillside Stranglers Kenneth Bianchi and Angelo Buono. Bianchi had confessed to five slayings of young women here and two in the State of Washington, but confessed on condition that he be committed to a prison in this state rather than Washington, where conditions were more Spartan. There was, however, a proviso that he testify “truthfully and completely” against his cousin and co-defendant, Buono.

Philibosian beseeched then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge (now California Chief Justice) Ronald George to banish Bianchi to the State of Washington, and he prevailed.

“It was the kind of case that required the DA, himself, to appear,” Philibosian says.

“It was up to the DA to come in and say, ‘Uh-uh, he didn’t hold up his end of the deal.…He did not testify truthfully and completely.’ ”

Indeed, the trial—the longest in U.S. history, comprising two years and two months—had been elongated based largely on the flip-flopping testimony by Bianchi.

Philibosian also sat at the counsel table during one hearing in the McMartin Pre-School child molestation case, his purpose being, he explains, to underscore the significance of the motion being argued.

![]()

Philibosian recounts that he was able to persuade the Board of Supervisors to “unfreeze the freeze” that had been placed on hiring of deputy DAs. During his two years in office, he recites, he hired about 150 deputies…of whom, he boasts, “almost one-half were women and a third minorities.”

He was not engaging in reverse-discrimination, he insists, declaring that all of the lawyers he hired “were highly qualified.”

Assistant DA Reuben Ortega, Philibosian says, headed his effort to “encourage minority attorneys to apply.” Ortega—who later became a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, then a Court of Appeal justice, and is now retired—reflects:

“We were not trying to get just anybody because they fit into a particular category.”

Philibosian “wanted to see a good, broad spectrum” of people hired, Ortega says, but on the other hand, “we weren’t going to hire people who weren’t capable just to meet that goal.”

He tells of simply putting out the word that the DA’s Office was hiring and that there would be “an equal shake for everybody.” No extra points were given to women or minorities, the former jurist mentions.

“It didn’t happen, it wasn’t necessary,” he says.

![]()

Ortega was assigned by Philibosian to oversee the office’s Family Support Division. He had handled child support collections while in the DA’s Office from 1967-73. (He next went into private practice, then sat briefly as a court referee in Long Beach, and served as a Los Angeles Superior Court commissioner from 1977 until Philibosian hired him for the office’s No. Three spot in 1983.)

The procedure that was previously followed by the office, Ortega says, was to “get a court order” requiring a parent to pay child support, then let the arrearages “build up” and just “hope” the parent would pay.

Under Philibosian, there were “aggressive collection” efforts, he says.

Philibosian remarks that with respect to non-paying parents, Van de Kamp “would not prosecute them criminally,” instead resorting to civil contempt proceedings. “That simply wasn’t effective,” he insists.

“We arrested a whole bunch of people” for non-payment, Philibosian says. “People started paying.

“We took cars, we took boats.”

A 1983-84 report by the DA’s Office shows that prosecutions for failure to provide child support had increased by 700 percent since 1982.

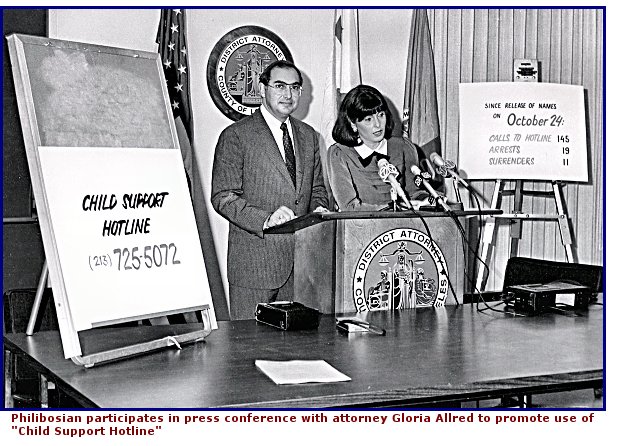

It was Philibosian’s hope that newspapers would publish, and TV stations would broadcast, names of parents who were delinquent in making payments. On Oct. 24, 1984, he released a list of 25 fathers who had spurned court orders to pay child support, and whose whereabouts were unknown. He asked that anyone knowing where the persons could be found telephone a DA’s hotline number.

The Los Angeles Times declined to cooperate in the effort, as did the Daily News. William F. Thomas, then editor of the Times, is quoted in a news story in his newspaper as saying that such lists would “have no intrinsic news values,” and that “[i]f we once started down this road, it’s hard to see where it would end or how our readers would be served.”

Philibosian remembers that someone at the Herald Examiner said, “Bring over the list.” The newspaper (now defunct) published the names.

![]()

The former DA brings to mind that when he entered office, feminist attorney Gloria Allred contacted him and asked if he were truly serious in his pledge to go after non-paying parents (nearly all fathers). He said he was, and they—a reserved, conservative Republican (he) and an outgoing, liberal Democrat (she)—worked together.

“He was very serious” in the mission, she now observes.

Allred notes that the idea of publishing the names was hers. She provides this assessment of Philibosian:

“He was not just a politician who would listen—and not do anything. He was interested in implementing anybody’s good ideas.”

By contrast, she and other feminists had picketed the DA’s Office when Van de Kamp led it, protesting what they saw as insufficient efforts to go after fathers delinquent in their payments. Allred camped out over a period of days on the 18th Floor of the Foltz courthouse waiting to meet with Philibosian’s successor, Ira Reiner, on the issue. She had what she describes as a “rather rocky relationship” with the next DA, Gil Garcetti, over his policy not to seek to arrearages, through civil proceedings, from fathers who were currently being prosecuted.

I’ll describe her battle with Reiner when telling of that DA’s administration.

Allred proclaims the current DA, Steve Cooley, to be effective in gaining compliance with support orders and prosecuting scofflaws. She says of him and Philibosian:

“They’re the best, as far as I’m concerned. They’re not looking to cover their political derrieres.”

![]()

Philibosian says he had a “very aggressive legislative program.”

One instance: he pushed for a police-horse protection bill, enacted in time for the 1984 Olympics. Officers on horseback would be used to control crowds. On previous occasions when mounted patrols had been used—including Raiders games—harm had been inflicted on horses through such means as hurling marbles under their feet, throwing beer bottles at them, or going so far as taking a knife or a club to them. Only vague and toothless cruelty-to-animals statutes applied.

Philibosian notes that he asked a deputy DA named Lance Ito to do the research and to draft the bill. (Ito is now a Los Angeles Superior Court judge.)

Edward M. Davis, now deceased, was a former Los Angeles police chief who had become a state senator. He carried the bill in the upper house; it passed there and in the Assembly, and was signed into law by Gov. George Deukmejian on July 1. An attack on a police horse was now an alternative misdemeanor/felony.

According to the 1983-84 report, his legislative program “ranged from omnibus child abuse legislation to narcotics, juvenile crime, rape, burglary and attacks on police officers.”

![]()

What sort of DA was Philibosian? A “terrific” one, according to Ortega, who says:

“He was enthusiastic. His first love was that office. He gave it all he had, 24-7.”

The retired justice credits his boss of long ago with being a “fellow who truly understood the workings of a DA’s Office,” as well as the workings of other county agencies.

Ortega makes note of Philibosian’s sharp mind, and says: “He grasps things very quickly.”

The office was “very professionally run—obviously because of him,” as the former assistant DA sees it.

He adds that Philibosian “knew how to be hands-on, but he knew how to delegate,” sensing when to take personal charge, and when it would be micro-managing.

Los Angeles City Attorney Carmen Trutanich comments:

“Philibosian was, for me, the quintessential DA. He was tough.”

He goes on to say:

“I worked in Compton under Philibosian. He stood behind his deputies.

“By and large, most people liked working for Philibosian.”

![]()

State Bar Governor Michael Marcus, a mediator and former State Bar Court judge, was a DDA who apparently didn’t like working for Philibosian. “He isolated himself from the troops,” Marcus says.

While predecessor DAs Joseph P. Busch, John Van de Kamp, and Evelle J. Younger were referred to by the troops as, respectively, “Joe, John, Evelle,” Marcus recalls, Philibosian was “either ‘the District Attorney’ or ‘Mr. Philibosian,” remarking: “Philibosian wanted to be known in those terms.”

Philibosian—who, as I’ve disclosed, is a friend of mine—is not someone with whom everyone can identify. He’s on the formal side. He’s not “one of the boys,” and is far from being a little boy who never grew up. He’s a man, and a gentleman.

In the 2006 book “Regards” by John Gregory Dunne and Calvin Trillin, there’s a discussion of joint appearances by Philibosian and Los Angeles criminal defense lawyer Leslie Abramson on ABC news shows discussing the O.J. Simpson case. “In the tiny studio they shared,” the book says, “Ms. Abramson called Philibosian ‘Bobby,’ although in his dark suit and serious tie he did not seem the Bobby type.”

Nobody who knows him calls him “Bobby.” And you can bet that dark suit was freshly pressed, and the tie was neatly knotted.

He’s meticulous in his appearance, just as he is in legal argumentation. He’s disciplined, precise, dignified, intelligent, and highly competent.

This isn’t to say he’s a fuddy-duddy. He’s a perfectionist with personality. He emcees this newspaper’s annual “Person of the Year” Dinner, as well as events of his alma mater, Southwestern Law School, those of the Armenian Bar Assn., and other groups.

Personality he has—but the makings of an ideal candidate, well, maybe not. He’s not a backslapper, not a phony.

He did have the makings of a DA, or a prosecutor at a higher level, but was defeated at the polls in 1984 by a super-politico, who did not have the makings of a district attorney.

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company