Metropolitan News-Enterprise

Monday, April 27, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Police, Miffed at DA’s ‘Operation Rollout,’ Line Up Behind Van de

Kamp’s Challenger

By ROGER M. GRACE

Ninety-First in a Series

JOHN VAN

DE KAMP

drew opposition in his 1980 race for reelection as district attorney from a

deputy who portrayed him as a foe of the police forces in this county.

“The peace

officers of Los

Angeles County have no confidence in

their current lawyer,” Sidney Trapp asserted in formally declaring his

candidacy on March 6...errantly implying that the county’s chief prosecutor is

a legal representative of the cities’ police departments.

On the

front page of the local section of the Los Angeles Times’s April 24 edition is

a story topped with the headline, “Officers Stage Protest at Dinner for Van de Kamp.”

It’s accompanied by a photo of a dour-pussed off-duty officer toting a poster

reading, “LA COPS WANT VAN de KAMP OUT.” The report begins:

“The

campaign for Los

Angeles County district attorney,

which so far has been a largely quiet affair, spilled onto the sidewalks of Beverly Hills Tuesday night when

about 50 off-duty police officers and sheriff’s deputies picketed a fund-raiser

dinner for incumbent John Van de Kamp.

“Van de Kamp,

like many of the 130 guests at the $250-a-person event was forced to brave the

peaceful bands of pickets to step inside posh Chasen’s restaurant.

“Many of

the protesters, joined by their wives and other family members, waved placards denouncing

Van de Kamp as ‘anti-police’ and supporting Deputy Dist. Atty. Sidney Trapp,

who opposes his boss in the June 3 election.”

(Van de Kamp

now looks back on that night with a degree of amusement, remarking: “And guess

who the guest of honor was that night. Carlton Heston was helping me raise

money.” The late actor, son of a deputy sheriff, was by 1980 associated with

conservative causes.)

Trapp drew endorsements from the Los Angeles Police Protective League (6,000 members), the

Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (4,000 members), Professional Peace Officers Association (2,900 members), the Peace Officers Research Association of California, Alhambra Police Officers Association, Arcadia Police Relief

Association, Azusa Police Officers Association, Baldwin Park Public Safety

Employees Association, Claremont Police Officers Association, Gardena Police

Benefit Association, Pasadena Police Officers Association, and Whittier Police

Officers Association.

Trapp drew endorsements from the Los Angeles Police Protective League (6,000 members), the

Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (4,000 members), Professional Peace Officers Association (2,900 members), the Peace Officers Research Association of California, Alhambra Police Officers Association, Arcadia Police Relief

Association, Azusa Police Officers Association, Baldwin Park Public Safety

Employees Association, Claremont Police Officers Association, Gardena Police

Benefit Association, Pasadena Police Officers Association, and Whittier Police

Officers Association.

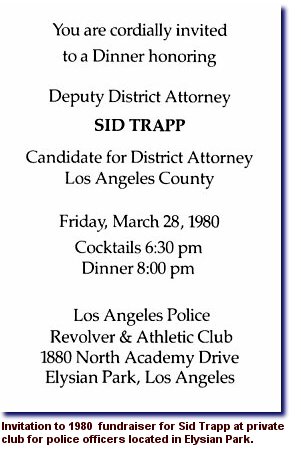

A

fund-raising dinner denominated on the cover of the invitation a “Law

Enforcement Salute to Deputy District Attorney SID TRAPP” was slated for March

28 at the Los Angeles Police Revolver & Athletic Club. That organization, anon-profit mutual benefit corporation established in 1934, is permissibly using city land, within Elysian Park, zoned “for use as public buildings and grounds,

including use as police training facilities and related purposes.” Assuming the

use of the facility for a political fund-raiser to have been lawful, it still

doesn’t meet the “smell test.”

Why were

the police up-in-arms

(figuratively) against the district attorney?

It harks to

an action by Van de Kamp in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of Eula Love on

Jan. 3,

1979 by Los Angeles police. Love was a

39-year old African American homeowner who raised such a ruckus when a

representative of the gas company came to shut off her service (owing to

nonpayment of her bill) that police were summoned. She brandished a knife; it’s

not clear, but she might have hurled it at one of the two responding officers

(which would have meant she was no longer in possession of a deadly weapon);

what is certain is that the officers fired at her and caused her death. If

their action was supported by necessity, the existence of that necessity was

not readily apparent, and there was an uproar.

As Van de Kamp

now recounts it in an interview:

“I think

Chief [Daryl] Gates later said it was ‘a bad shooting.’ We could not find

criminality because there was a self-defense argument. But at that point, we’d

had a succession of cases where there’d been police shootings, not just LAPD

but other shootings—very late reports to us of the shootings and the

investigations that were conducted by the police. It was just inadequate.

“So I

decided that you get word of a police shooting, we’d send an investigator and a

prosecutor right there to the scene of the incident, try to get through, talk

to as many witnesses as we could and get a full understanding of what had happened

at that particular time. So we did that, and then we would write up our

investigative results, and in most cases they were within the boundaries. But

at least we’d have almost immediate reports on file, publicly.”

The deputy

DA and office investigator would, like police, “roll out” to the scene of the

shooting, and the new procedure was tagged “Operation Rollout.”

The former

DA goes on to recount:

“We had

major resistance from LAPD when we established it….[T]he police, I think, were

concerned that we were somehow trying to abuse them by doing this. It was just

the opposite. We took the pressure off of the police, put the pressure on

ourselves. Certainly the community response to these kinds of things would then

turn to us in these cases. We’d have to explain what happened. At least we knew

that we had a fairly objective investigation.”

Police

were not accustomed

then to conducting probes of shootings by officers—or any other

investigations—with someone looking over their shoulders. This was well before

the time of reality shows capturing arrests on videotape. Back then, proposals

for scrutiny of police actions by civilian panels—termed “police review

boards”—were viewed by many as left-wing efforts to discredit and demoralize

police departments.

Police

regarded themselves as the investigators of possible criminal wrongdoing and

saw prosecutors as those who took cases to trial after police had reached

conclusions and made arrests—which did, indeed, reflect the tradition

differentiation of their respective roles. So, adverse police reaction to the

revolutionary “rollout policy” was, at the time, understandable. Police viewed

Van de Kamp’s teams as intruders. The notion that a second set of eyes at a

police shooting scene, belonging to a non-police examiner, could lend credence

to any exoneration by police investigators, did not strike a responsive chord;

police viewed themselves as being quite capable of keeping their own house in

order.

Resentment

within the LAPD was intensified by virtue of official deference being

deflected, to an extent, from one of their own—a lieutenant they respected,

who had been heading inquiries into officer shootings for a dozen years without

outside interference—and posited, in part, in the deputy district attorney

heading the Special Investigations Division, Gil Garcetti (later district

attorney).

Van de Kamp

recalls a “guy by the name of Higbie” who was “always there” at scenes of

police shootings and who “would keep our people as far away from the scene of

the event as possible, have the witnesses go out the back door on many

occasions so we couldn’t talk to them.”

He alleges

that it “was very difficult to deal with Higbie, who was very protective of his

own people.”

The man he

has in mind is then-Lieutenant Charles A. Higbie, who headed the unit that

probed “police officer-involved” shootings. Conflict between the DA’s office

and police agencies—and with Higbie, in particular—was to continue after the

election.

As to the

impact on the election, Van de Kamp recalls that police hostility to him

stemmed “primarily” from Operation Rollout.

There

was something else, he says, that rankled some law enforcement

officers.

“I think

some police thought we were too tough on our filing policy,” the former

district attorney—now of counsel to Dewey Lebouf—brings to mind.

“[I]f it

was a felony charge,” he says, “we had to make sure that we had evidence of a

felony, that we could convict, prove [the charge] beyond a reasonable doubt, to

an objective jury.”

Van de Kamp

charges that district attorneys’ offices in “many” other counties “would file

anything that walked in the door and then plead everything out at the Municipal

Court—basically getting misdemeanor convictions—just bargaining cases out,

wholesale.”

Trapp

alleged that Van de Kamp permitted too many crimes, seen by police as felonies,

to be tried by city attorneys’ offices as misdemeanors. That mirrored a

campaign claim in 1976 by Van de Kamp’s chief challenger, Vincent Bugliosi. In

neither election was the public roused.

Another of

Trapp’s themes was that if elected, he would disseminate the sentencing records

of judges. He faulted Van de Kamp for not making it known to the public who the

lenient sentencers were. A Trapp campaign leaflet says:

The only

way the justice system can reduce crime is to make the cost of committing a

crime outweigh the potential benefit. This means that lenient judges must be

forced to mete out sentences which protect the community. If they refuse, they

must be replaced at the polls. [¶] The judges have refused to release their

sentencing histories to the voters for fear that some of them will be voted

out. Van de Kamp has refused to publish this data to the voters (even though he

compiles it in a computer paid for by your tax dollars) because he is afraid of

losing political support of the judges. Unless this data is released, you will

have no way to evaluate the criminal court judges at election time. And the

judges will have no incentive to change their sentencing practices.”

With

respect to the prospect of Van de Kamp “losing political support of the

judges,” judges were precluded then by ethical strictures, as they are now,

from supporting candidates for non-judicial offices.

Trapp maintained

that Van de Kamp engaged in too much plea bargaining. The May 31 issue of the

Van Nuys News (now the “Daily News”) reports that the preceding day, the

president of the Police Protective League said at a press conference: “We’re

concerned about plea bargaining that results in returning burglars, rapists and

robbers back into the community.” What the would-be emotion-stirrers failed to

do, however, was to present hard evidence that perpetrators of provable

felonies were being let off lightly if they simply “copped a plea.”

The vote in

the June 3 primary was 1,019,438 for Van de Kamp (64 percent) and 580,077 for

Trapp.

Trapp,

reflecting on the 1980 race, tells me he has only “one big regret” about it,

that being: “I lost.”

He says

that while his campaign “did not carry the day,” it served a purpose.

“I made a

few points, I guess, and I pointed out where there were some weaknesses in the

incumbent DA,” Trapp remarks.

He insists

that Van de Kamp “was not a tough DA, at all.”

The current

district attorney, Steve Cooley, Trapp opines, is “fair, and tough when he’s

supposed to be.”

Cooley does

not, however, have reciprocal praise for Trapp. He terms his bid for office in

1980 a “rogue candidacy” and remarks:

“He clearly

wasn’t in the same league with John Van de Kamp.”

He says Van

de Kamp was, among the district attorneys in the county’s history, “way up

there” in his performance.

Trapp

retired as a deputy DA in 2002. Divorced, he remarried, and his second wife is

the deputy district attorney in charge of asset forfeitures in drug cases. He

now spends time at his hobby: flying.

A

development in the June 3, 1980 primary, other than Van de Kamp’s triumph, was former

Assemblyman Mike Antonovich outdistancing incumbent Baxter Ward in a four-way

contest for a seat on the Board of Supervisors. That forced the

newscaster-turned-politico into a November run-off.

In the last

days of the campaign, a July 16 letter from Van de Kamp was produced by

Ward...the release of it being so timed as to create an illusion of backing

from the DA…who had, in fact, not chosen up sides in the race.

Ward had

prompted a 1977 board inquiry into allegations that county Assessor Philip

Watson had given tax breaks to political contributors, including former State

Bar President Joseph Ball (chief counsel to the Warren Commission). Antonovich

cited that probe as an instance where Ward’s “muckraking” had cost taxpayers

money.

Van de Kamp

went to bat for Ward to the extent of confirming that although Watson had not

been indicted, the inquiry wasn’t groundless. The state’s former attorney

general now reflects:

“I sent

[Ward] a letter in July in response to a request from a Ward aide—and then they

held it, and used it for political purposes. It was released by Baxter, not by

us. We didn’t release it for political purposes, but I gather that Antonovich

was making political claims, so Baxter was defending himself. That’s fair game,

it seems to me, on both sides.”

Whether or

not there had been adequate cause in 1977 for investigating Watson (who had in

1966 been indicted for taking bribes, but acquitted), it can’t be doubted that

Ward did, through his two terms, covet publicity through a procession of meritless

probes and trumped up exposes. Antonovich won in November, 1980, putting an end

to that.

Ward,

Watson and Ball are now deceased.

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company

MetNews Main Page Perspectives

Columns

Trapp drew endorsements from the Los Angeles Police Protective League (6,000 members), the

Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (4,000 members), Professional Peace Officers Association (2,900 members), the Peace Officers Research Association of California, Alhambra Police Officers Association, Arcadia Police Relief

Association, Azusa Police Officers Association, Baldwin Park Public Safety

Employees Association, Claremont Police Officers Association, Gardena Police

Benefit Association, Pasadena Police Officers Association, and Whittier Police

Officers Association.

Trapp drew endorsements from the Los Angeles Police Protective League (6,000 members), the

Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (4,000 members), Professional Peace Officers Association (2,900 members), the Peace Officers Research Association of California, Alhambra Police Officers Association, Arcadia Police Relief

Association, Azusa Police Officers Association, Baldwin Park Public Safety

Employees Association, Claremont Police Officers Association, Gardena Police

Benefit Association, Pasadena Police Officers Association, and Whittier Police

Officers Association.