Monday, March 23, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

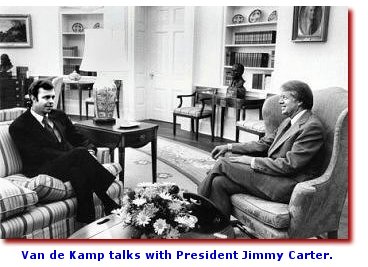

Van de Kamp in 1977 Is on Short List of Five for Appointment as FBI Director

By ROGER M. GRACE

Eighty-Eighth in a Series

JOHN VAN DE KAMP, 20 months after entering office as Los Angeles County district attorney, became a top contender for appointment to the post of FBI director.

The Los Angeles Times—in a front-page, banner-headline story on June 9, 1977—broke the news that Van de Kamp’s name and that of William Lucas, whom it identified as “a black ex-FBI agent who is sheriff of Wayne County (Detroit) Mich.,” were among five on the list of finalists that would be submitted by an evaluation committee to President Jimmy Carter and Attorney General Griffin Bell.

The Times, at that point, did not have the other three names.

Van de Kamp tells me he was later advised—perhaps by somebody in the White House, but he’s not sure—that he was Number One on the list.

The day after the Times’ scoop, accounts differed as to the level of Van de Kamp’s interest in the post.

The report in the Times says that Van de Kamp “definitely” would accept the job, if offered to him, and quotes him as saying:

“I enjoy what I am doing here but it is a challenge that no prosecutor could turn down.”

By contrast, an article in the Valley News says:

“Van de Kamp yesterday expressed ‘surprise’ at reports that he was among five people being considered by President Carter to become the next FBI director.

“Van de Kamp, who was waiting in the county board of supervisors hearing room to request additional funding for his department said he had been interviewed by the president’s selection committee.

“He said it was ‘premature’ for him to discuss whether or not he would accept the post if it were offered. ‘I’d have to see what stipulations and conditions were attached,’ he said, adding, ‘It will be a great challenge for whoever takes the job.’ ”

![]()

The president on June 12 publicly identified the five names that were submitted to him by the vetting committee. Aside from Van de Kamp and Lucas, the list included Neil Welch, a special agent who was in charge of the FBI’s office Philadelphia; John Irwin Jr., a judge of the Massachusetts Superior Court; and Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Harlington Wood Jr. of Chicago.

Carter is quoted in a United Press International dispatch as saying:

“We may or may not choose one of these five, but the likelihood is that we shall.”

Van de Kamp appeared to be in a strong position. However, a June 15 analytical piece in the Long Beach Press Telegram points out why an appointment might not be a boon, saying:

In the days of J. Edgar Hoover no member of Congress dared to lay a glove on the FBI. Not so anymore.

Rep. Don Edwards, D-Calif., a pre-World War II FBI agent himself, has had the General Accounting Office go over the FBI’s books with a finetooth comb.

As a result the FBI has been forced to admit that much of its annual claim of savings to the taxpayers has little foundation in fact. And the FBI has reduced its domestic surveillance cases from the thousands to the hundreds.

At the moment the FBI and the Justice Department are pleading with the Congress to write “a charter” for the FBI to tell it what it can and cannot do.

Congress in return is asking the FBI to provide it with a list of FBI-committed burglaries. And some members of Congress, including acidtongued Rep. Robert Drinan, D-Mass., want the FBI to tell the people who it worked against just exactly what was done to their friends, jobs and marriages.

So the new director will face problems of morale within his agency, suspicion on the outside, attacks from Congress and the certainty that new controversies are on the horizon.

In the case of Mr. Van de Kamp, he won’t even be able to escape Los Angeles smog. Washington has its own version and the price of housing may be even higher there than at home.

The ten-year-appointment as FBI director may not be as attractive as it seems. Today the FBI is almost in as much disrepute as it was the day J. Edgar Hoover took over in 1924.

![]()

Hoover, for decades, was among the most revered of the nation’s public officials. No thought was entertained by the public prior to the 1960s that there could be abuses within the FBI.

By the time Richard Nixon became president in 1969, in a contentious and rebellious era when heroes were routinely denigrated (and n’er-do-wells exalted), Hoover—whose service had perhaps gone on too long—came under intense scrutiny. The year before, Congress had passed the legislation limiting terms of future FBI directors to 10 years. Nixon was asked if Hoover possessed his confidence, and the president answered in the affirmative.

In the years immediately following Hoover’s death on May 2, 1972, the late director became an increasingly controversial figure and the agency was placed under a microscope. It plummeted in public esteem.

Clarence Kelley, who succeeded Hoover, was respected…but the FBI had not, by the time Van de Kamp was interviewed by Carter in 1977, regained high stature in the public’s eye.

Yet, Carter expressed—or feigned, to see the reaction—a contrary view.

Van de Kamp says:

“I had a very interesting conversation with the president. Walter Mondale took me in. I knew the vice president slightly, over the political wars….I had my 15 or 20 minute conversation with the president.

“[At one point] he said,

‘Don’t you think that the FBI is held in higher repute today than it has been

in many years?’ And I said, ‘No, I do not. I think that there’s a real feeling

of malaise about the FBI right now in the country and I think there’s an awful lot

that’s going to have to be done.’”

“[At one point] he said,

‘Don’t you think that the FBI is held in higher repute today than it has been

in many years?’ And I said, ‘No, I do not. I think that there’s a real feeling

of malaise about the FBI right now in the country and I think there’s an awful lot

that’s going to have to be done.’”

Van de Kamp recalls the president giving one of his distinctive Carteresque grins, and says that the reality hit him that “I just told the emperor that he has no clothes.” He says he instantly consoled himself with the thought that “Well, that’s fine—I told the truth.”

Van de Kamp notes:

“I was told later, and I don’t know where this came from, that he liked the fact that somebody would tell him that he was wrong.”

![]()

The interview took place July 14. By then, the prospect of Van de Kamp landing the job looked good…but not great.

There had been these developments:

•Lucas’s chances shriveled in the wake of a June 24 report in the Los Angeles Times saying that the finalist “has acknowledged that while sheriff he twice accepted free air transportation and hotel rooms as part of Las Vegas gambling junkets.” The article quotes Lucas as saying he did nothing wrong. Yet, it didn’t look right.

lThe Times—which zoomed in closely on the selection process and the finalists—demeaned the significance of a prospective appointee making it onto the list of five. Its June 26 investigative report—which shaped coverage nationally—brings into the question the methodology employed by the nine-person committee (which included California Court of Appeal Justice Cruz Reynoso, who was soon to be a member of the state Supreme Court, and Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley). The article contains an admission by the chair, DuPont Chief Executive Officer Irving Shapiro, that members went largely on “gut judgment,” lacking the benefit of any in-depth investigations of the 60 contenders winnowed from the initial 230-or-so prospects, and put forth its short list of five names without those five having undergone a thorough check.

•That same June 26 article raises questions as to whether FBI bureau chieftain Welch’s subordinates committed burglaries in the course of obtaining Socialist Workers Party documents. Shapiro is quoted as expressing obliviousness to the concern, saying: “You have facts I don’t know.”

•The report also takes aim at Van de Kamp and the Massachusetts judge, Irwin, remarking that while “[n]o questions have been raised about the competence or integrity” of either, “reporters for the Times were told in Los Angeles and Boston that both men might lack the experience needed to tame the entrenched bureaucracy of the FBI.” Before taking charge of the Los Angeles DA’s Office, Van de Kamp had been an assistant U.S. attorney and then interim U.S. attorney in Los Angeles, director of the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys, supervising all 93 U.S. attorney’s offices across the nation, and was the first federal public defender in Los Angeles. The Times article continues: “Critics in Los Angeles charge that Van de Kamp has not been sufficiently vigorous in investigating charges of improper activity by law enforcement agencies.” The LAPD had shredded complaints against officers that had not been sustained, acting on authority of the Office of City Attorney…which later admitted it has erred as to the law; Van de Kamp found no basis for prosecuting the officials involved.

•A July 3 Times article says that Welch was “fast emerging as a front-runner in the race” but appeared to be a “cop with a short fuse who sometimes takes things very personally.”

•The Times’ July 12 edition includes the revelation that FBI chief counsel John Mintz, who had tied with two others for the Number Six spot on the list and was favored by FBI Director Kelley, a member of the panel of nine, was being considered by Carter and Bell.

•On the morning of Van de Kamp’s July 14 employment interview with the president, an article in the Times quotes an unnamed Los Angeles Superior Court judge “who has FBI contacts,” as labeling the DA “a child,” and saying that the “FBI bureaucracy will eat him alive.” The article remarks: “A youthful looking 41, Van de Kamp is hard pressed to rebut suggestions that he may not seem old enough or tough enough for the job.”

Van de Kamp was the same age as Mintz who had just been brought in as a possible selection, signaling that 41 was not too young to be in contention. Bell, upon whom Carter was relying in making the choice, was 58; Carter was 52.

![]()

An Aug. 16 UPI dispatch from Washington says the president would formally announce the next day that he was selecting U.S. District Judge Frank Johnson of Alabama.

Bell had previously tried to recruit Johnson, but the jurist had not been interested until a point quite recent when his mother, for whom he had been caring, went into a nursing home.

Van de Kamp tells me that Johnson “was a famous, highly esteemed federal judge—who had a civil rights record that was dramatic.”

A month-and-a-half later, however, the Los Angeles DA was back in the running for the FBI post after Johnson withdrew as the nominee on Nov. 29 in light of the slowness of his recovery from surgery.

An Associated Press report the following day says:

“As the talent search resumes, speculation turned first to four men who were recommended last June by a presidentially appointed screening committee.

“ ‘We still have the list,’ ” Bell said, adding that he does not feel any more bound by it now than he was before.”

(The dispatch refers to “four men” because Wood withdrew from consideration on July 27 for undefined personal and family reasons.)

![]()

The Nov. 30 issue of the MetNews, in an unbylined article by then-political editor Jack Brown, says:

[I]f Van de Kamp—a front-runner for the position before Johnson was tabbed—is, in fact, interested in becoming FBI chief, he isn’t showing it.

Despite Johnson’s failure to rally after major surgery, Van de Kamp still isn’t counting him out.

The DA told the MetNews:

“I thought Johnson was an excellent choice for the job. If there is any chance in the next 4-6 months that he could pick up the position, after all, the country would be well-served to have an interim director in the meantime.

“He [Johnson] seemed to meet all public acceptance and requirements for the position.”

Asked if he were still available for the job, himself, Van de Kamp said:

“I am happy doing what I’m doing. It’s a tremendous opportunity for service.

“I never solicited the consideration for the FBI position. I was asked to go back to Washington for an interview.”

He did not say, directly, that lacked interest in the job—but evinced no enthusiasm or anxiety over his prospects.

“I get a third hand report that Atty. Gen. [Griffin] Bell will take a couple weeks to decide what to do, but I have just not been asked at this point,” Van de Kamp reported.

As Van de Kamp now recites:

“Bell went to the justice from the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, Bill Webster—who was someone he knew. I think Webster was a good FBI director.”

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company