Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Joan Dempsey Klein, William B. Keene Mull Challenging New DA, John Van de Kamp

By ROGER M. GRACE

Eighty-Fifth in a Series

JOHN VAN DE KAMP, as 1976 opened, was raising funds and plotting strategy in preparation for the June 8 primary election. He had been appointed as Los Angeles County district attorney less than two months earlier to fill a vacancy, and he was determined to hold onto the post.

The question was: who would challenge him?

Former Deputy District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi, lead prosecutor in the Charles Manson murder trial, had made it clear that he would be running. Given his proclivities and his track record, his candidacy would mean loose charges being flung, and possibly a tight race being run.

In addition to Bugliosi, these three were prominently mentioned as possible contenders:

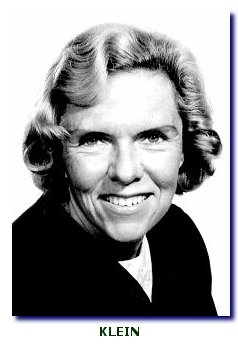

•Joan Dempsey Klein, a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court. Initially, she wanted to gain the post through appointment by the Board of Supervisors after incumbent Joseph Busch died June 27, 1975…and was among other judges with that aspiration.

But County Counsel John Larson pointed out in a written opinion to the board that the state Constitution barred appointment of a judge during his or term of office as district attorney. Since 1966, Art. VI, §17 has provided: “A judge of a court of record…during the term for which the judge was selected is ineligible for public employment or public office other than judicial employment or judicial office.”

Klein—who was to be appointed a Court of Appeal presiding justice in 1978 and who still serves in that capacity—insisted then that the provision denies due process and equal protection to those prospective candidates who are judges.

![]()

She pooh-poohed Larson’s opinion, pointing out that a Los Angeles Superior Court judge in 1970 held that a judge could, lawfully, be appointed DA. The July 14, 1975 issue of the Los Angeles Times quotes Klein as saying:

“A court decision certainly takes precedence over a county counsel opinion.”

The decision to which she alluded was made Nov. 30, 1970, by then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Richard Schauer, later the court’s presiding judge. (As a trial court decision, it was non-precedential, leaving the board free to conform to the county attorney’s contrary interpretation.)

Schauer had determined that Los Angeles

Municipal Court Judge James DiGiuseppe could lawfully be appointed district attorney to replace

incumbent Evelle Younger, who would take office in January as state attorney

general. The jurist reasoned that if DiGiuseppe assumed the new post, it would

not be “during” his term as a judge because that term—through not slated

to end until 1980—would immediately be terminated when he took a new,

inconsistent oath of office.

appointed district attorney to replace

incumbent Evelle Younger, who would take office in January as state attorney

general. The jurist reasoned that if DiGiuseppe assumed the new post, it would

not be “during” his term as a judge because that term—through not slated

to end until 1980—would immediately be terminated when he took a new,

inconsistent oath of office.

A Dec. 1, 1970 report in the Valley News and Green Sheet says that “[f]rom the bench, Schauer made it clear that he is not under consideration himself for Younger’s office and would not accept it if it were offered.” Schauer later became a Court of Appeal presiding justice and is now retired.

The provision, though blocking a consideration by the Board of Supervisors in 1975 of appointing Klein, did not prevent the judge from running for the office in 1976.

It specifies: “A judge of a trial court of record may, however, become eligible for election to other public office by taking a leave of absence without pay prior to filing a declaration of candidacy”—a proviso that had been upheld by the Court of Appeal for this district in 1973.

So, Klein—a deputy attorney general from 1955-63—as well as Keene and other judges could have challenged Van de Kamp in 1976…but with the disincentive of going without a salary while running.

![]()

Klein contemplated doing so.

The Jan. 22 issue of the Los Angeles Times contains a news story telling of a breakfast meeting the day before at Klein’s home. Present were Klein and her husband, Conrad Lee Klein, Van de Kamp, and the DA’s campaign manager, Barbara Yanow Johnson (wife of a future Court of Appeal justice, Earl Johnson Jr., now retired).

Van de Kamp is quoted as recounting: “I told [Klein] I felt I would beat her in the race, but that obviously she was the master of her own destiny on that.”

The Jan. 27 issue of the newspaper reports that Klein announced at a press conference that she was not running, saying:

“I have been weighing a number of factors in arriving at a decision. Obviously one is the availability of substantial financing in an election year already crowded with other candidates.”

The article notes:

“Klein has said it would cost a minimum of $200,000 to organize even a modest campaign for district attorney. Estimates are that Van de Kamp could raise and spend as much as $500,000.”

If she had run, it would almost certainly have, at the least, forced Van de Kamp into a run-off—a fate he avoided by prevailing over his five opponents in the primary by attaining nearly 52 percent of the vote. It was not simply that she would have drawn votes as a woman. There was, in the end, a woman in the race, but one who was obscure and without meaningful financing. Gender was not enough to render her formidable. Klein had three advantages:

—Her ballot title would have been a potent one. Younger had been elected district attorney in 1964 as a Los Angeles Superior Court judge. Goodwin J. Knight held that position when he was elected lieutenant governor in 1946, and Stanley Mosk held it when he was elected attorney general in 1958. (Knight later became governor and Mosk ascended to the California Supreme Court.)

—Klein had name recognition. She was a frequent speaker at meetings, had a solid reputation among those seeking to advance the interests of women as professionals, and had been a Los Angeles Times “woman of the year” in 1975.

—She could have raised money in the primary…not as much as Van de Kamp, but enough that she would have been formidable as a contestant. Had she made it into a run-off—which is entirely conceivable—Klein surely would then have attracted finances from across the nation; at that juncture, her gender would have become a magnet for support. The “women’s movement” was experiencing an upsurge at that period. A real prospect of a woman being elected district attorney of Los Angeles County would have inspired a major push.

![]()

Did Klein ever have regrets over not having run for DA? “Absolutely not,” she’s says, adding:

“I don’t know why I ever had that in mind.”

The jurist says she was thoroughly enjoying her service on the Superior Court.

Running for district attorney, Klein reflects, “would have been a real tough go.” In order to raise adequate financing, “you’ve got to put your soul in hock,” she quips.

Klein also notes that district attorney contests have become “too politicized” and says she wouldn’t have felt “comfortable” with that.

Campaigning in a judicial race was different for her—that she enjoyed, the presiding justice remarks. Klein, a Democrat, had been appointed in 1963 to the Los Angeles Municipal Court by Democratic Gov. Pat Brown but couldn’t gain an elevation by Republican Gov. Ronald Reagan...so she ran for the Superior Court in 1974, prevailing in a field of eight candidates. She won in a run-off with the only other woman in the race, then-Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Bonnie Lee Martin.

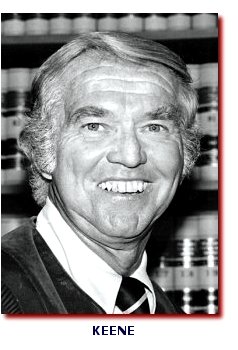

•William B. Keene, also a Los Angeles Superior Court judge.

Keene, an outstanding member of his court, bright and affable, really wanted to be DA. He never attained that goal but garnered money and national recognition in portraying the judge for seven years on television’s “Divorce Court” (from 1985 to 1992).

The Feb. 21, 1975 installment of this column reports:

“As it’s shaping up now, Dist. Atty. Joseph P. Busch Jr. may

be facing a heavyweight opponent at the next election: Superior Court Judge

William B. Keene.

“As it’s shaping up now, Dist. Atty. Joseph P. Busch Jr. may

be facing a heavyweight opponent at the next election: Superior Court Judge

William B. Keene.

“Judge Keene told this column he hasn’t made up his mind yet whether or not he’ll run for the office in 1976…but added: ‘Ever since I was a deputy district attorney [from 1953-57] I was intrigued with that job.’ ”

Los Angeles Magazine had speculated that Busch might be spared a 1976 contest through appointment to the Los Angeles Superior Court. Busch’s press deputy, Jay Berman, told me that wasn’t in the offing, and Keene related that Busch had advised him that he wasn’t interested in a judgeship. The column notes:

“But Judge Keene adds he would be happy to trade jobs with Busch…and comments: ‘I think Joe Busch would make a hell of a judge.’ ”

Busch died June 27, 1975. Keene filed a writ petition in the California Supreme Court to establish his eligibility to be appointed DA. (He had done the same thing in 1970 but before the high court could act, the supervisors appointed Busch.) The 1975 bid failed in the state’s top tribunal; the petition was denied on July 23. Determined, Keene filed a federal action. He sought a temporary restraining order blocking an appointment before his challenges to the state constitutional provision could be considered. The Long Beach Independent Press-Telegram’s edition of Sept. 4 reports on an action the previous day:

“In dismissing Keene’s action, U.S. Judge Warren Ferguson termed the suit ‘utterly frivolous.’ ”

Keene opted in 1976 not to run. He now explains:

“I thought it would be too much to undertake and I was leery of my chances of success.”

Van de Kamp was “the better candidate” when compared to Bugliosi, he comments, hailing the incumbent’s “intellect” and “his abilities,” and characterizing Bugliosi as a “showboat.”

He points out that Bugliosi appeared in his courtroom in the Manson case. Keene was the first judge in that case, eventually acquiescing to a pre-trial challenge by Manson, resulting in the case being lobbed into the courtroom of Judge Charles Older (since deceased).

“I didn’t have that high an opinion of Bugliosi,” Keene says, elaborating: “I watched him in court.”

•George V. Denny III, Beverly Hills private practitioner. Denny, who had been a deputy district attorney from 1959-62, was one of the unsuccessful applicants for appointment to the post by supervisors in 1975.

In the early part of 1976, newspaper accounts lent him the image of a serious contender for election. At the end, he was lumped in with other minor candidates. When votes were tallied, he came in last in a field of six contenders.

Nonetheless, Denny might have had some impact on the election. It could be that his blasts at Bugliosi—a foe with whom he had engaged in litigation—cost the erstwhile celebrity prosecutor votes.

His allegations were that:

—Bugliosi gave a woman with whom he had been having an affair $450 after she told him she was pregnant, the money to be used for an abortion. He learned that she had lied, broke into her apartment on June 25, 1975, and beat her up.

—Bugliosi used his position as deputy district attorney to obtain the unlisted phone number of his former milkman and harassed him and his wife over a three-month period, finally paying them $12,500 as “hush money.”

The charges—which Denny also disseminated in 1972 when Bugliosi ran against Busch and in 1974 when he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for state attorney general—were denied by Bugliosi.

Denny went on to become president of the Criminal Courts Bar Assn. in 1985. He now lives in Texas.

The electorate in 1976 awarded votes as follows: Van de Kamp, 911,476; Bugliosi, 634,237; Deputy District Attorney Joseph Howard, 76,302; Deputy District Attorney Mildred Friedenberg, 69,110; Deputy Public Defender Christopher Smith, 41,894; and Denny, 26,553.

Next time: more about Bugliosi’s ill-fated campaign effort.

![]()

FOOTNOTE—Under a 1991 Court of Appeal opinion, the prohibition on appointment of a judge to a non-judicial post applies only to a judge who had been elected to a six-year term. The governor only appoints persons to fill vacancies, and “the tenure of an appointee cannot be deemed a ‘term’ within the meaning of the Constitution,” according to the opinion. Under its reasoning, Klein, elected in 1974, would not have been eligible for appointment as DA in 1975, nor would Keene, nor other state judges who had been mentioned as possible appointees but who had been elected to terms ending in 1978 or 1980. They included a past presiding judge, and future TV judge, Joseph. A. Wapner, as well as DiGiuseppe. Had thinking in 1975 coincided with that of the appeals court 16 years later, the board would have had the option of selecting William Ritzi, assistant district attorney under Younger, whose term as a Superior Court judge ended Jan. 5, 1976…provided, that is, that supervisors would have been willing to wait that long to put a new DA into office. Van de Kamp was appointed Oct. 9, 1975.

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company