and because he knew how to

try cases. It’s just that he didn’t really know how to be the district

attorney.

and because he knew how to

try cases. It’s just that he didn’t really know how to be the district

attorney.

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Joseph P. Busch Jr.—Swell Guy, Able Trial Lawyer...Serves as DA Without Distinction

By ROGER M. GRACE

Eighty-First in a Series

JOSEPH P. BUSCH JR. was appointed in 1970 as Los Angeles’ 36th district attorney after U.S. District Judge A. Andrew Hauk turned the job down. He served only three-and-a-half years, dying from a heart attack stemming from alcoholism.

He’s remembered fondly by those who worked in

the office based on his affability and good nature,  and because he knew how to

try cases. It’s just that he didn’t really know how to be the district

attorney.

and because he knew how to

try cases. It’s just that he didn’t really know how to be the district

attorney.

And he almost wasn’t.

His predecessor, Evelle Younger, was running for attorney general in 1970, and it was generally assumed that if he won, his chief deputy, Lynn D. “Buck” Compton would be appointed by the Board of Supervisors to replace him as DA.

He had at least three votes lined up, Compton tells me, but says of a possible ascension to the post of DA: “I didn’t relish it.”

It cannot be doubted that Compton would have been an outstanding district attorney, and might well have succeeded Younger as attorney general, and perhaps become governor. But Compton was out of contention for the DA’s post after he was sworn in June 15, 1970, as a member of Div. Two of this district’s Court of Appeal, nominated a month earlier by Gov. Ronald Reagan.

Younger made Busch his chief deputy on June 22, and publicly announced that “he will be my recommendation” for appointment by the board as district attorney, should the office become vacant.

Younger won; the board met behind closed doors (as it lawfully may) on Nov. 30 to choose the person to replace Younger upon his assuming the new post on Jan. 4. There was no enthusiasm for Busch among the members.

Political partisanship, reports in the Los Angeles Times reveal, played a role in the selection by supervisors (nonpartisan officeholders) of a new district attorney (also holder of a nonpartisan office). The two Republicans, Warren Dorn and Burton Chase, favored state Sen. George Deukmejian, R-Long Beach, who had lost out to Younger in the GOP gubernatorial primary. Supervisors Kenneth Hahn and Frank Bonelli, Democrats, wanted former U.S. Attorney William “Matt” Byrne to get the post. Supervisor Ernest Debs, also a Democrat, wouldn’t back Byrne because, as federal prosecutor, he had gained a conviction of friend of Debs in connection with rigging card games at the Friars Club.

The board was deadlocked; neither Deukmejian nor Byrne could muster three votes. (The former went on to become state attorney general, then governor, and Byrne gained appointment to the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, eventually serving as its chief judge.)

Others who wanted the post but did not have the votes included Assemblyman James Hayes, R-Long Beach (who would become a Los Angeles County supervisor) and attorney Richard Mosk (now a member of Div. Five of this district’s Court of Appeal).

Continuing with renditions in Times stories: out of the blue, Bonelli proposed appointing Hauk; Hahn and Dorn assented; Hauk was offered the job by telephone; he thought about it overnight; he said “no” because it would have meant giving up his federal pension.

Hauk, a decade later, gained major news media attention. The Los Angeles Daily Journal did a profile on him; buried in it was a remark he had uttered in sentencing an illegal alien from Mexico:

“We let all these Iranian ignoramuses in, but not this young man who wants to support his child. And he isn’t even a fag, like all those faggots from Cuba we’re letting in.”

Other reporters recognized the remark as having news value and drew attention to it. Probes into the jurist’s conduct by KABC-TV and other news outfits (the MetNews included) showed that Hauk habitually displayed biases, blabbered what should not be said, and was cantankerous.

From the county’s standpoint, it was fortunate that Hauk spurned the job offer.

![]()

Busch was selected, unanimously, on Dec. 1. The Long Beach Independent’s report the next day quotes Debs, the board chair, as terming Busch “a first choice practically from the beginning for almost every member of the board.” Why, then, was there a stalemate the day before?

A report in the Times’ on Dec. 2 relates that Chace “said Busch was the only person who could muster three votes.”

It would seem that Busch was a compromise candidate who was no supervisor’s top choice.

![]()

The new DA was highly regarded within his office, as well as among the criminal defense bar. One deputy he hired is now the county’s district attorney. Steve Cooley terms Busch “a great human being…a very jovial, outgoing good guy” who was “very popular among the people who knew him.”

Hailing Busch as “a terrific trial lawyer” is Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Senior Judge Stephen Trott, who was chief deputy district attorney under Busch’s successor, John Van de Kamp. He says Busch knew “what a case was worth.”

Also in the DA’s Office when Busch was in charge was Wilber Sweeters, who characterizes Busch as “one of the guys” and “somebody you could talk to without any problem at all.”

Veteran criminal defense lawyer Richard Hirsch, a deputy district attorney from 1967-71, recalls that Busch “was one of the great trial deputies of the DA’s Office,” was “loved by everybody,” was “very accessible,” and “was just the most wonderful, supportive guy in the world.”

Another longtime criminal defense lawyer is Joe Ingber. “Everybody loved Joe because he came through the system…Joe had been through the wars,” he remarks. Busch had been in the office since 1952.

![]()

Curt Livesay—who was chief deputy district attorney from 1979-83, and who resumed that role from 2001-06—was a trial deputy under Busch, stationed in Long Beach. One day, he recalls, the judge told him during the recess:

“I have the DA on the phone. He wants to talk to you. He’s really upset.”

Livesay, who now divides his time between ranching in Oklahoma and serving of counsel to the Long Beach law firm of Trutanich-Michel LLP, recounts that the district attorney began:

“Livesay, this is Joe Busch. I’ve been reviewing your work….”

The young prosecutor must have been as apprehensive as Bob Cratchit, after sneaking in late on the day after Christmas, when Scrooge bellowed:

“Well, my friend, I’m not going to beat around the bush. I’m simply not going to stand [for] this sort of thing any longer. Which leaves me no choice….”

Scrooge’s next words were…“and therefore I am about to raise your salary.” Busch’s words were: “I’m going to appoint you head deputy.”

Pointing to the good nature of the county’s 36th district attorney, Livesay says that Busch “always had advice for anyone in the hallway.”

![]()

A testimonial to Busch comes from criminal defense lawyer Harland Braun—an outspoken critic of Busch during the 1972 election contest, in which the incumbent was challenged by Deputy District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi. A Los Angeles Times article appearing Oct. 25 of that year quotes Braun as saying in a prepared statement:

“The facts are that there is no training program to speak of in the district attorney’s office, and deputies are sent into court wholly unprepared for the serious cases which they handle.”

The article relates that Braun said in an interview that “[t]he true feeling of the deputy DAs, even those who are supporting Joe Busch, is that the office needs a competent administration....”

Braun now reflects:

“I supported Vincent Bugliosi openly. Joe Busch never held it against me.”

To the contrary, he says, Busch, soon after the election, assigned him to prosecute four followers of Charles Manson. (Braun gained convictions of them on Feb. 21, 1973 for committing two hold-ups—one entailing a theft of 143 weapons, apparently to be used in an effort to break Manson out of prison.)

“Joe was the kind of guy that if you did something up front and open, he understood,” Braun says.

He tells of J. Miller Leavy, director of the DA’s office’s central operations sections, coming into his office one day, starting out:

“Braun, I hear you’re supporting Bugliosi.”

He says Leavy (a legendary trial lawyer) indicated he fervently hoped Busch would win, but assured him that “this is America” and he was entitled to back whomever he wished, and instructed that if anyone gave him a hard time, “You let me know.”

Braun remembers Busch “hanging out” in the lunchroom at the Hall of Justice that was dubbed “Leavy’s Deli”—it being the place where J. Miller Leavy ate bagels. He says Busch “liked to be one of the group.”

![]()

He apparently even wanted to be a “good guy” to at least one individual from whom he should have distanced himself.

Michael Marcus, now a mediator, was a deputy in the DA’s Office from 1969-85. While Busch headed the office, he was assigned to the Organized Crime and Pornography Division.

One day, he tells me, Busch summoned him to his office. He found Busch alone with a well-known figure: mobster Mickey Cohen (whom Busch, as a trial deputy, prosecuted in 1962, unsuccessfully, for complicity in the murder of a fellow member of the “underworld.”)

Sitting there in the office of the chief prosecutor of the county, with no one witnessing what was said, was the man described in the 1993 “World Encyclopedia of Organized Crime” by Jay Robert Nash as having been the “[t]rigger happy boss of the Los Angeles and Las Vegas underworld.”

The “Encyclopedia of Gangs” by Louis Kontos and David Brotherton, published this year, denominates Cohen “a feared racketeer” who “could be ruthless and brutal when he felt threatened by a rival mobster.”

It’s true that Cohen was no longer actively linked to the rackets. He had been released Jan. 7, 1972 from federal prison after nearly a decade of incarceration based on his income tax evasion conviction, and was in ill health. But should Busch—whose integrity has never been in doubt—have admitted a caller who in earlier days was known to have made routine payoffs to city and county personnel?

Marcus, presently a member of the State Bar Board of Governors, was then a young deputy who was, understandably, uneasy. Then came Busch’s directive:

“Michael, I want you to tell Mr. Cohen the facts of the Sica case.”

Joseph Sica was a longtime associate of Cohen. He was a “local gangland” member, according to a look-back in a Nov 12, 1976 Jim Murray column in the Times.

As Marcus remembers it:

“Mickey was there to tell Joe [Busch] that Joe Sica was a nice guy and would never commit extortion.”

Extortion was a crime for which Sica had been tried in the past.

Marcus says he obliged, reciting some of the evidence…but held back on certain information and, upon returning to his desk, prepared a memo “for the file” setting forth what had transpired.

Marcus—a State Bar Court judge from 1995-2001 who has lectured extensively on ethics—remarks that Busch’s conduct was “not an ethical violation,” but, he asserts, reflected “bad judgment.”

![]()

Echoing what others say, Marcus refers to Busch as “a man of the people, a nice guy” who “always meant well,” and was a “great trial lawyer.” But, he adds, Busch was “not a good administrator.”

Some I talked to, remembering Busch fondly, skirted questions as to Busch’s administrative abilities. For example, Herbert M. Jacobowitz, who was president of the Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorneys Assn. in 1972 and publicly defended the incumbent against Bugliosi’s charges, responds to such a query now by saying of Busch, nonresponsively:

“He surrounded himself with good people. He had a good chief deputy [John Howard].”

Without directly criticizing Busch, Jacobowitz

does say that his successor, John Van de Kamp, was “the better administrator.”

Cooley says of Busch, politely: “I don’t think he was around long enough before he died to make his mark.” Yet, Busch was there for about three-and-a-half years. Younger, in his first three-and-a-half years had made a mark…and so had Cooley in that period of time.

From what I can discern from persons who don’t want to be quoted, while Busch was DA, professionalism in the office waned, and boozing among deputies became rampant.

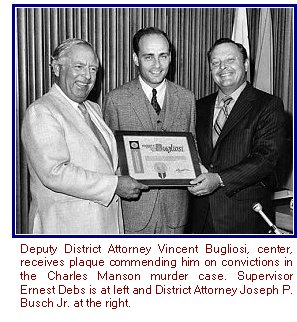

Bugliosi charged throughout his campaign that office morale was low. Some of his charges appear to have had substance, and a worthier challenger might have prevailed. As it was, Bugliosi—the prosecutor of Manson, and unsuccessful candidate for attorney general in 1968—lost by only 12,116 votes. His campaign, matching his personality, was brash. Busch came across as honest and sincere, which he was, while Bugliosi projected an image of being too flamboyant, too polished, too enamored of himself.

The irony is that Busch would have been better off if he had lost the contest. The stress of the job drove him to a steady consumption of alcohol in copious amounts, resulting in his death.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company