Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

O’Brien Charges Younger With Having ‘Slush Fund,’ Giving Favors to Donors

By ROGER M. GRACE

Seventy-Fifth in a Series

EVELLE J. YOUNGER was subjected during the 1970 run-off for the post of state attorney general to a barrage of charges, largely centering on the allegation that as district attorney of Los Angeles County, he had maintained a “slush fund,” and doled out favors to those donating to it. The favors, his Democratic opponent in the Nov. 3 general election maintained, included writing a virtual “character reference” for a man under suspicion of crimes, and allowing a defendant in the Tate-La Bianca slayings case to give a press interview, creating the prospect that any convictions in the case would be reversed. The defendants included Charles Manson.

The Democratic nominee, Chief Deputy Attorney General Charles A. O’Brien, showed little concern for accuracy in his quest to be quoted.

Former Gov. George Deukmejian, then a state senator, is quoted in an Oct. 15 Herald-Examiner article as telling reporters at a press conference that O’Brien was “carrying out a preconceived, packaged smear campaign...of unsubstantiated attacks.” And so he did.

![]()

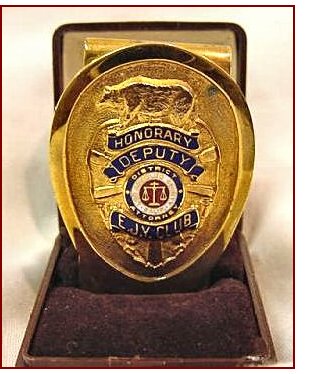

There was no “slush fund.” Contributors of $250 in 1966-69 to Younger’s non-campaign political fund would become members of the “EJY Club” and receive a money clip with a facsimile badge on it, like this:

Or, the donor could opt for a pair of cuff links, each with a mock badge on it.

This bit of gimmickry reminds me of the “premiums” a person can receive for donating to KCET.

A Republican aspirant for the attorney general’s post, Spencer Williams, questioned during the primary whether the bestowing of the mementos by the EJY Club—which by then had been disbanded—violated the law. Penal Code §146d provided (and still does): “Every person who sells or gives to another a membership card, badge, or other device, where it can be reasonably inferred by the recipient that display of the device will have the result that the law will be enforced less rigorously as to such person than would otherwise be the case is guilty of a misdemeanor.”

The keepsakes, which cost about $3.80 each to produce, were far too small to be confused with actual shields. Both a set of cuff links and a money clip rested on the fingers of a man with his hand palm up in a photo in the Los Angeles Times on May 12, 1970. DAs subsequent to Younger—including incumbent Steve Cooley—have given out to visitors to their offices, and to others, tiny mock DA badges in the form of pins, as souvenirs. None of the DAs has been charged with a misdemeanor, and it is doubtful that any bearer of these items has been able to flash them to beat a speeding ticket. The trinkets are in marked contrast to the full-size, official reserve officer badges then-Orange County Sheriff Michael Carona distributed to those forking over $1,000 donations to his campaign in 1998.

Sales of EJY Club “memberships,” with miniature toy badges as prizes, was no doubt legal and harmless, but somewhat inane, and destined to attract gibes. The practice had ended before it drew public criticisms, with contributions routed to Younger’s 1970 campaign coffers in the AG race, unless a donor objected, in which case the money was refunded.

![]()

O’Brien drew attention to the money clips and cuff links at two Sept. 23, 1970, press conferences in the course of lambasting Younger for bestowing “favoritism” on EJY Club members.

At a press conference in Los Angeles, according to an Associated Press account, O’Brien said of his adversary:

“At worst, he has impaired equal enforcement and protection of the law. At best, he has indulged in seedy, old-fashioned shakedown politics.”

Later that day in San Francisco, O’Brien described Younger’s account as an “Eastern style slush fund,” the AP story says.

The dispatch quotes Younger as labeling the charges as “absurd and gutter politics” and insisting EJY Club members had enjoyed no special treatment.

A “shakedown,” in the relevant context, is “[e]xtortion of money, as by blackmail,” according to the American Heritage Dictionary.” O’Brien never pointed to an involuntary relinquishment of funds by anyone to the EJY Club.

The same dictionary defines a “slush fund” as “[a] fund raised for undesignated purposes, especially: [¶] a. A fund raised by a group for corrupt practices, such as bribery or graft.” The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy uses the term less restrictively, saying: “Though slush funds may be used for legitimate purposes, such as paying state employees, the term is generally used to describe money that is not properly accounted for and is being used for personal expenses and political payoffs.”

O’Brien thus, at the least, implied that the money raised by the EJY Club was earmarked for unlawful purposes. This was a bold charge, yet never substantiated.

An Oct. 16 McClatchy Newspapers Service article, datelined Sacramento, reports:

“Charles A. O’Brien, Democratic nominee for state attorney general, today declared that regardless of whether he is elected next month he will pursue an investigation of his opponent’s ‘slush fund.’

“If elected, said O’Brien during a news conference in the Capitol, he will institute an investigation of the Los Angeles district attorney’s office….

“If he is not elected, O’Brien said, he will, as a private practicing attorney, seek an investigation by ‘the bar association.’ ”

O’Brien was not elected and—would you believe it?—Younger was not disbarred.

![]()

At a press conference on Sept. 29, O’Brien charged that Younger in 1967 supplied a lawyer who was an EJY Club member with what “was practically a character reference” for a client, and that the client paid the lawyer $2,000 for the service.

A $2,000 fee for merely obtaining a letter from the district attorney would reasonably give rise to a suspicion as to a sharing of that fee—that is, a payoff to the DA—or the calling in of a favor, such as a preexisting membership in the EJY Club.

The client was later convicted in U.S. District Court in connection with the rigging of card games at the Friar’s Club in Beverly Hills through such devices as a ceiling peephole and electronic signaling.

The Sept. 30 edition of the Oakland Tribune recounts that O’Brien told reporters in Los Angeles that receipt of the $2,000 payment was acknowledged by the lawyer in testimony.

“You don’t have to take Charlie O’Brien’s word for it,” the article quotes the candidate as saying, “here are the Grand Jury transcripts.”

One reporter who apparently took a look at the transcripts was Richard Bergholz, a political writer for the Los Angeles Times. Bergholz was widely regarded in Republican circles as a journalist whose accounts were frequently slanted to the left. Bergholz’s Sept. 30 unbylined report on O’Brien’s charges was the one mentioned here yesterday to which Younger took exception in a letter to the editor. Ironically, it’s that very report which debunks O’Brien’s claim that the lawyer admitted deriving a $2,000 fee for exacting a letter from Younger.

![]()

Here’s Bergholz’s rendition:

“The man who sought and got the letter was attorney Paul Caruso, who testified he was still owed $5,000 for civil work he had done previously for the Friar’s Club defendant, Maurice H. Friedman.

“Caruso said Friedman asked him to get the letter to satisfy Nevada officials inquiring into his eligibility for a gaming license. He said he refused to do anything further for Friedman unless the back debt was paid, and Friedman thereupon paid him the $2,000.”

What amount, if any, Caruso charged for obtaining the letter is not mentioned.

The article quotes Younger’s July 14, 1967 letter to Caruso as stating that “I am advised that at present there is no investigation or grand jury proceeding pending which involves Mr. Friedman.”

That does not strike me as resembling a “character reference.”

The Times quotes Younger as saying:

“We get hundreds of requests from lawyers every month asking if we have anything going involving their clients, and we routinely answer them all.”

The article goes on to report:

“O’Brien said it was unthinkable that the district attorney would not have known about the pending federal investigation....”

Younger, chief prosecutor for the County of Los Angeles, wrote a letter in his official capacity attesting to the lack of any pending county investigation of Friedman. It is doubtful that it would have been within the scope of his duties, or at all appropriate, to stick in any gossip pertaining to the status of any state or federal investigation, and certainly not to convey, gratuitously, any concrete knowledge of any such probe gained in confidence.

Yesterday I alluded to an on-the-fly interview I had with O’Brien in which he said: “I’ve brought up the Friars Club case, in which [Younger] worked against the FBI.” How did the ex-FBI agent act to thwart a law enforcement agency? Here’s the answer from a Sept. 30 McClatchy Newspapers Service story:

“[O’Brien] said he had no objection to revealing whether a man is under investigation, but never in writing. But he charged Younger with saying Friedman was not under investigation while in fact, he was, by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

“‘It’s a damn, damn rare instance when, instead of working with the FBI, you work against them,’ he declared.”

So, by not mentioning the FBI investigation that was in progress, Younger impeded the FBI, under O’Brien’s theory. How inventive.

![]()

O’Brien blasted Younger on Oct. 26, 1970, for risking reversals of any convictions in the Tate-LaBianca murder case. He did that, O’Brien explained, by having provided the opportunity for one of the defendants, Susan Atkins, to tape record her story “for publication and financial reward.”

He charged that she was allowed to leave jail on Dec. 1 and Dec. 4, 1969, to meet with her attorney, Richard Caballero, at his office. It was there that she made the recordings. This was done, he insisted, based on both Cabellero and Deputy District Attorney Aaron Stovitz falsely stating in declarations under penalty of perjury that the purpose was to determine what her plea would be and the nature of her testimony before the grand jury. on Dec. 5.

An article in the Oct. 26, 1970, edition of the Oakland Tribune quotes O’Brien as saying:

“I have never known of a case in which a suspect in a murder case who is being held without bail, was allowed to leave the jail to visit an attorney’s office. This is a clear case of unequal enforcement of the law, of Mr. Younger jeopardizing ultimate convictions in a major murder case.”

He alleged that Younger granted the favor to Caballero because he was associate of Paul Caruso, who had paid $250 for membership in the EJY Club. (The 1976 Court of Appeal opinion upholding the convictions says that Caruso and Cabellero “shared office space, overhead and courtesies.”)

There were some problems with O’Brien’s allegations. He told reporters at a San Francisco press conference that Cabellero and Stovitz each executed a declaration as to the purpose of the visit, and he provided them with two declarations. He apparently didn’t notice that both declarations were signed by Cabellero.

A Los Angeles Times article the next morning attributes this statement to Stovitz:

“I did not sign any affidavit. I merely approved a removal order for Susan Atkins to be taken to her attorney’s office. I believed the affidavit to be true and in good faith.”

What’s more, Stovitz—who had just been yanked off the Manson case by Younger and was hardly in a mood to go to bat for his boss—insisted “[i]t was solely my decision” to go along with the furlough, and that Younger knew nothing of it.

![]()

O’Brien made various other charges. He dug up the 1964 allegation made in the DA’s race by the then-incumbent, William McKesson, that Younger, as a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, was a weak sentencer, particularly in child molestation cases—a contention refuted at the time by the court’s presiding judge.

Hopping on the O’Brien bandwagon was Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty, quoted in the Oct. 1 issue of the Times as telling reporters the day before at his press conference:

“Without equivocation, having dealt with the district attorney many years, watching him work with [publisher] Otis Chandler and the Los Angeles Times, watching him file criminal complaints against our police officers in cases which were dismissed by a judge later without even letting the officers go before a grand jury, I’m certainly going to vote for O’Brien.”

In the end, O’Brien lost. As a Times’ retrospective of Nov. 8 sizes it up:

“In part, Younger’s triumph was attributed to the presence on the ballot of Peace and Freedom Party candidate Mrs. Marguerite (Marge) Buckley of Venice. She picked up 174,479 votes, most of which presumably would have been cast for the Democratic candidate if her name had not been on the sheet. Younger’s margin of victory was 90,777.

Younger’s win was not impressive, but he emerged from a contest marked by mud-slinging with none of the sludge sticking to him. Meaningfully, he was without mud on his own hands.

Late last August, I tried to contact O’Brien for his reflections on the campaign of 38 years ago. I telephoned his home one afternoon and was told he was upstairs asleep, and that his son was handling his affairs. He died Sept. 3, at the age of 83.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company