Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

‘There Has Been Intimidation of the Press in This County’ by Younger, AG Opponent Claims

By ROGER M. GRACE

Seventy-Fourth in a Series

EVELLE J. YOUNGER, district attorney of Los Angeles County, wanted to be governor. In 1970, he undertook to get to his destination by the route taken by Earl Warren and Edmund G. “Pat” Brown: from the post of district attorney (Warren in Alameda County and Brown in San Francisco)…to the office of state attorney general…to the Governor’s Mansion. The path to the AG’s Office in 1970, following the primary, was littered with red herrings and muck…and Younger was not the one who put them there.

In the Republican primary, Younger defeated a future governor, state Sen. George Deukmejian of Long Beach, as well as state Sen. John Harmer of Glendale and Spencer Williams, secretary of the state Human Relations Agency. The Democrats put up the No. Two person in the state Attorney General’s Office, Charles A. O’Brien.

While the election for attorney general was close, the respective credentials of the candidates weren’t. O’Brien was a hothead who desperately sought to win the election through mud-slinging.

Today and tomorrow, I’ll take a look at his accusations, starting with one that had a semblance of validity, proceeding to those that were hokum.

![]()

It was 38 years ago that I wrote the following portion of this column. It appeared “here,” in a sense. It was published as “editorial analysis” on Oct. 30, 1970 in the Los Angeles Enterprise, a newspaper which merged with the Metropolitan News in 1987. Sizing up the 1970 AG’s race….

Chief Deputy Attorney General Charles O’Brien is pitted against Los Angeles District Attorney Evelle Younger. The main thrust of O’Brien’s campaign has been attacks on Younger for having an alleged “slush fund.” Younger acknowledges that attorneys and others have purchased memberships in the E.J.Y. clubs, but denies any impropriety.

Just this week, O’Brien blasted the district [attorney] for allowing a principal in the Tate-La Bianca murder trial to take part in an interview for publication. The public statements might complicate the appeals process, he charged.

The campaign is in marked contrast to the one four years ago, in which Attorney General Thomas Lynch released statement after statement putting forth constructive proposals for improving the administration of justice in California. Lynch was the only Democrat elected to statewide office that year.

However, O’Brien is incensed by any suggestion he is waging a smear campaign.

“I think that’s nonsense,” he told this paper. “I’m talking about sworn affidavits. I’m talking about sworn testimony in court. I’m talking about affidavits given under oath. What the Hell are we talking about, about, a smear campaign? Frankly, I get very angry about that. I opened these issues by documenting, from court cases, the statements of judges and the sworn testimony of witnesses under oath. The only person who has yelled ‘smear’ has been Mr. Younger, because he has not responded once, not once, to a charge that I have made.

“I think, frankly, that there has been a failure here on the part of the press to press him, to push him, to give an answer. He has yet to answer one charge, on court records, on sworn testimony, on an affidavit. Not one.

“I’ve brought up the Friars Club case, in which he worked against the FBI; I’ve brought up the Tate-LaBianca case, in which he worked to prejudice the ultimate conviction of the persons accused of most gruesome murder in the history of this state; I’ve talked about the (Jerry) Weber ease, in which there was a lawyer convicted of soliciting a bribe from a member of his office. And Mr. Younger has gotten away with no answers. Not one answer.

“I don’t think the district attorney of one other county would have been able to get away with what Mr. Younger has been able to get away with….There has been intimidation of the press in this county.”

Younger responded:

“Over the years, the Attorney General’s Office has had nothing but praise for my office. Then, a few weeks ago, Mr. O’Brien found it necessary to begin his political smears after the polls showed him behind. I believe my administration warrants the confidence the Attorney General’s Office had theretofore vested in it.

“I find it particularly significant,” he continued, “that 38 out of the state’s 58 district attorneys, both Democrat and Republican, are supporting me, while only three are backing Mr. O’Brien. One hundred former FBI agents and former deputy attorneys general have formed a committee to support my candidacy. Law enforcement throughout California overwhelmingly favors me.

“I am especially proud that the President of the United States appointed me as chairman of the National Task Force on Crime and Law Enforcement.”

The district attorney pointed out that his office has instituted a close-circuit television training program for law enforcement agendas throughout the state and a monthly legal information bulletin. These efforts ought to have been undertaken by the state Attorney General’s Office, Younger claimed.

![]()

I remember the interview with O’Brien. The candidate was loudly ranting. I don’t recall interviewing Younger and am fairly certain, from the broad nature of the comments quoted above, that what I got was merely a written response provided by Younger’s press deputy, Jerry Littman. I was young, and I apparently failed to press for direct responses from the candidate. This was a matter of being “green,” not “yellow”; I wasn’t intimidated by Younger, and surely other members of the press corps, whether neophytes like me or seasoned ones, weren’t.

I have known candidates (particularly in judicial races) who have been intimidated by reporters, afraid to speak with them, but I’ve never known a reporter intimidated by a candidate.

Yet, the supposed “intimidation” of the press in Los Angeles County by Younger was a theme in the latter part of O’Brien’s campaign, starting with an Oct. 13 speech in Santa Monica. A McClatchy Newspapers Service story on Oct. 16 reports that O’Brien “said he came to Sacramento to make accusations against Younger because, he contended, Younger has ‘intimidated’ newsmen in Los Angeles.”

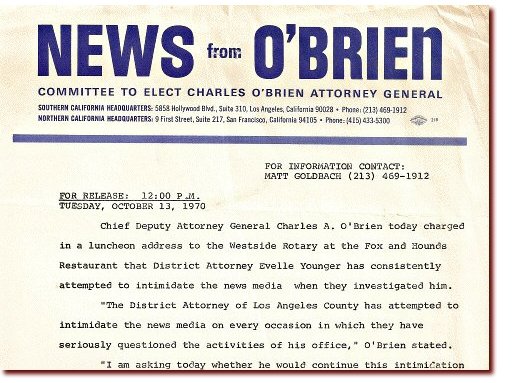

An Oct. 13 O’Brien press release begins:

Chief Deputy Attorney General Charles A. O’Brien today charged in a luncheon address to the Westside Rotary at the Fox and Hounds Restaurant that District Attorney Evelle Younger has consistently attempted to intimidate the news media when they investigated him.

“The District Attorney of Los Angeles County has attempted to intimidate the news media on every occasion in which they have seriously questioned the activities of his office,” O’Brien stated.

“I am asking today whether he would continue this intimidation if he were elected Attorney General with the much more formidable powers and authority held by that office….

“There are four cases currently in which Mr. Younger has challenged the accuracy of completely factual news accounts concerning his office.”

O’Brien’s press release scores Younger for complaining to the Federal Communications Commission in 1968 about allegedly slanted reports by a radio station, KLAC, in connection with an ill-fated prosecution of a man on sex charges, a prosecution that drew criticism from the judge. The FCC was hyperactive in those days in enforcing its “Fairness Doctrine” (since repealed), and Younger was hypersensitive about news reports he felt were slanted against him. In retrospect, if he questioned the fairness of the radio station’s accounts, he should have exercised his own First Amendment rights by publicly disputing what was reported rather than seeking governmental reprisals based on journalistic activity. It might well be said that the intended effect of Younger’s action was intimidation—obviously, to his discredit—but it remains that O’Brien’s pronouncement was that “[t]here has been intimidation of the press in this county”…yet, he failed to show anything indicating that KLAC had, in fact, been intimidated.

![]()

Another of the four “cases” entailed Younger’s complaint to the management of KTLA, Channel 5, about commentaries by newscaster George Putnam on Jan. 4 and 5, 1968, in connection with Younger’s decision not to oppose a new-trial motion on behalf of a man convicted of the slaying of two little girls. My column of Aug. 19 details that event and the aftermath, and maintains that Younger’s “counter-offensive to Putnam’s adverse coverage was one of the few ill-considered actions of his administration.” But here’s what O’Brien’s press release alleges:

“[T]he District Attorney sought to have Los Angeles newscaster George Putnam fired from television station KTLA.”

The press release goes on to say:

The press release goes on to say:

“The District Attorney tried to have Putnam fired—he was suspended for a day.”

Younger did protest alleged unfairness by Putnam and threatened to complain to the FCC. No facts emerged at the time of the flap in 1968, or were pointed to by O’Brien in 1970, showing that the DA sought to have Putnam fired. Putnam was under contract. Displeasing the DA is hardly a breach of contract.

There was momentary uneasiness at KTLA over the prospect of a complaint to the FCC and Putnam was ordered by news director Stan Chambers to “lay off” the story; Putnam, not intimidated, declined to pledge compliance with the directive, and he was barred from the air that night; the next day, Putnam and his lawyer met with station management, and restrictions on his speech were lifted. That night, Putnam again blasted Younger. In the end, Younger caused intimidation neither of the journalist nor the station.

![]()

The statement continues:

“In the third instance, when Los Angeles newscaster Pete Miller of KTTV broke the story of the actions of the District Attorney’s investigators and attorney Jerry Weber, the D.A.’s investigators attempted to intimidate and eventually sued Mr. Miller. The actions of the D.A.’s investigators which Mr. Miller disclosed on television were proven in the court trial which convicted Mr. Weber of soliciting a bribe.”

Weber had sought money from a client, who was under suspicion of murder, in return for using his purported influence with the DA’s Office to ward off the filing of charges. He asked for $25,000 as a pay-off to two specific DA’s investigators, as well as a $10,000 fee for his own services. Weber—prosecuted by the Office of Attorney General in light of the aspersions he had cast on the DA’s investigators—was convicted on June 8, 1970, of soliciting a bribe. There was no evidence that the investigators were actually on the take. The Valley News on June 9, 1970 says: “Dist. Atty. Evelle J. Younger has denied anyone on his staff knew of, or was involved in, a bribe.”

O’Brien did not dispute that directly…though his press release implies to the contrary in saying, without elaboration: “The actions of the D.A.’s investigators which Mr. Miller disclosed on television were proven in the court trial which convicted Mr. Weber of soliciting a bribe.”

Whatever cause of action the investigators maintained against Miller had nothing to do with Younger. There was no showing that Younger had intimidated Miller, or even tried to do so.

And O’Brien’s statement to me that “there was a lawyer convicted of soliciting a bribe from a member of [Younger’s] office” was either a serious boner or a fabrication; Weber sought a bribe from a client, a financial adviser, who had no connection with the DA’s Office.

![]()

“And finally,” the press release quotes O’Brien as saying, “Mr. Younger complained only this month to the Los Angeles Times about the completely factual reporting of my charges that the District Attorney had shown favoritism in the Friar’s Club gambling case. In this case, the victim of Mr. Younger’s attack was L. A. Times political writer Richard Bergholz.”

What Younger did on that occasion was what he should have done with respect to Putnam’s commentaries—that is, he exercised his own First Amendment prerogative. He wrote a letter to the editor; it appears in the Oct. 2 edition of the Times under the headline, “Younger Rebuts O’Brien on ‘Influence’ Charge.”

The bulk of it is comprised of countering assertions by O’Brien. Contrary to O’Brien’s insistence in my interview with him, Younger had, in fact, responded to specific campaign allegations of his opponent at various junctures in the campaign.

Contrary to O’Brien’s characterization of Bergholz as a “victim” of the DA, the letter merely contains two comments by Younger that he was “surprised” by specified elements of Bergholz’s story.

Was the Times intimidated by Younger? Was Bergholz? Hardly. The Times printed Younger’s letter, followed by a brief rebuttal by Bergholz.

![]()

O’Brien failed, nearly in toto, to substantiate his claim that Younger had intimidated the press in Los Angeles County. Nearly because here was the short-lived suspension of Putnam.

He failed to show that Younger “has attempted to intimidate the news media on every occasion in which they have seriously questioned the activities of his office”…unless the KLAC reports and Putnam’s commentaries were the only such occasions.

Beneath it all, there was a basis for criticizing Younger, but O’Brien exaggerated and distorted.

What of O’Brien’s insistence that Younger had a slush fund? That he had jeopardized any convictions that might be won in the Tate-La Bianca murder case? That he worked against the FBI in the case involving rigged card games in the Friar’s Club?

All of it was false. I’ll get to that in the next column.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company