Monday, August 25, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

District Attorney Younger Takes Hits From the ‘Maverick Mayor’

By ROGER M. GRACE

Sixty-Ninth in a Series

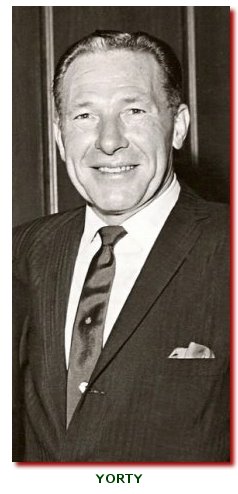

EVELLE J. YOUNGER, while district attorney of Los Angeles County, drew the accusation that he was controlled by the Los Angeles Times. That allegation came from Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty.

The charge was implausible…but typical of Yorty.

The scrappy mayor’s propensity, when faced with adversity, was to go on the offensive. So, when three former members of the city Board of Harbor Commissioners (one of whom had died in a mysterious drowning) and one present member—all appointed by Yorty—were indicted Dec. 28, 1967 for bribery, “Mayor

Sam” had to lash out at somebody.

Harbor Commissioners (one of whom had died in a mysterious drowning) and one present member—all appointed by Yorty—were indicted Dec. 28, 1967 for bribery, “Mayor

Sam” had to lash out at somebody.

According to the indictment, the four had awarded a $12 million contract for construction of the World Trade Center—not the one now existing in downtown, Los Angeles, but one proposed to be built on Terminal Island—on a no-bid basis to a firm owned by a city human relations commissioner, who also was indicted. A private conversation was tape recorded in which the construction company chief claimed that orders for his firm to get the contract had come from the Mayor’s Office.

At a Dec. 29 press conference, Yorty declared:

“I’m concerned about the Times dominating the District Attorney’s Office.”

That office, he commented, was “in a position to wield tremendous power, and this may be dangerous to our community.”

He contended that the grand jury had acted in the matter because he had requested that it do so.

At a press conference on Jan. 4, 1968, Younger insisted:

“I make each decision to file or not to file a felony complaint consciously, to the best of my ability and base that decision on the facts and the law.

“No newspaper, organization or individual has enough influence or muscle to get me to make a decision on any other basis.”

In this instance, however, it was not his own decision to bring the charges; it was the grand jury that indicted, he pointed out, declaring that he does not “control the grand jury.”

Younger revealed that at the time the mayor made his request for a grand jury probe, one was already in progress, having been launched months before.

The Times, in a series of articles, had pointed to improprieties in the operations of the Harbor Department. The DA denied that his office was acting in tandem with the Times, saying:

“The fact is that the Times has tremendous resources. They have had a task force of trained reporters working on this case for months….

“Times reporters have on occasion interviewed potential witnesses before we were able to do so.”

By the end of the year, the three surviving ex-harbor commissioners were convicted; charges against the developer were dismissed in 1970 after a judge ruled key prosecution evidence (in the form of electronic eavesdropping) to be inadmissible. One of the convictions was reversed in 1970 based on instructional error.

![]()

Yorty’s 1968 slap at Younger in connection with the indictments was not the mayor’s only assault on the county prosecutor. As recited here last week, Yorty lambasted Younger around that same time for his decision to desist from opposing a defense motion for a new trial in the case of a convicted murderer of two little girls. Younger’s call was based on his impression (correct or not) that the accused’s lawyer had provided an inadequate defense while intoxicated.

There were other instances of discord.

Younger’s son, retired Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Eric Younger, tells me that his impression was that his father (who died in 1989) and Yorty (who died in 1998) had been “friends.”

That apparently had been so prior to the indictments. The Dec. 14 edition of the Long Beach Press Telegram quotes Yorty as telling reporters of having telephoned Younger to complain of mistreatment of witnesses before the grand jury in the Harbor Department investigation, saying: “I just called him on the phone. You know, we’ve been friends for a good many years.” A Jan. 5, 1968 article in the Times reports, “The district attorney said he considers himself a friend of Yorty, even though the mayor ‘makes it a little tough at times to be his friend.’ ” While a friendship might later have been reestablished, at least for the balance of the time Younger was DA, his relationship with Yorty was a rocky one.

![]()

The 1968 primary took place on June 4. In Los Angeles County, Younger was reelected as district attorney—to no one’s surprise; he had only token opposition from one Michael B. Hannon, an ex police-officer who had been in practice for just under two years. The major focus that day was on California’s Democratic presidential primary, won by U.S.Sen. Robert F. Kennedy of New York. Shortly after midnight, RFK was shot with apistol at the Ambassador Hotel by Sirhan Sirhan. He died later that day.

Time Magazine’s April 14 issue recites:

“District Attorney Evelle Younger and State Attorney General Thomas Lynch…were aghast, and said so, when Mayor Yorty went before a news conference [on June 5, prior to Kennedy expiring] to divulge what he described as the contents of Sirhan’s private notebooks, found in the Sirhan home.

“According to Yorty, Sirhan wrote that Kennedy must be killed before June 5, the first anniversary of the last Arab-Israeliwar, a date that has detonated demonstrations in some Arab countries. Sirhanwas also said to have written ‘Long live Nasser.’ Yorty went on to characterize Sirhan as pro-Communist and anti-American, and to imply that he might have had some extremist connections. In contrast, the police and prosecutor had been bending over backward to protect Sirhan’s legal rights—advising him of his right to counsel and his right to remain silent, calling in a representative of the American Civil Liberties Union to watch out for the suspect’s interests.”

A UPI dispatch in the immediate aftermath of the shooting says that “Younger Thursday [June 6] expressed concern during a news conference over release of information that might prejudice the case” and “cautioned restraint on all evidentiary matters by the mayor, police and newsmen.”

The next day, according to an AP report: “Younger told reporters the assassination was a great tragedy and would be a‘greater tragedy...if successful prosecution of the person responsible for theterrible crime were jeopardized by statements prior to the trial commenting on evidentiary matters.’ ”

![]()

Yorty on Oct. 16, 1968, again portrayed Younger and the Times as his enemies who were conspiring against him.

He alleged that the DA’s Office had offered immunity to two persons if they would implicate him in some sort of criminal wrongdoing—but they couldn’t. The mayor noted Younger’s closeness to Los Angeles Times Publisher Otis Chandler and claimed that the two were working for his political demise “so the Times can get the mayor back again.”

In running for mayor in 1961, he had portrayed the incumbent, Norris Poulson, as a Times pawn.

One of the ex-Harbor Department commissioners, George Watson, was then on trial. Yorty insisted that the indictment would not have been handed up “had we a more fair attitude by the district attorney and a grand jury more free of district attorney domination.”

![]()

Yorty put his foot in his mouth on May 7, 1969, in asserting that Younger had blocked the grand jury inquiry which he had requested into allegations that City Councilman Tom Bradley’s favorable 1965 vote on a request for a conditional use permit stemmed from a $1,000 pay-off by a developer. Yorty was seeking reelection, and Bradley was Yorty’s opponent in the May 27 run-off.

Yorty’s reaction to the grand jury deferring any action until after the election, as reported the next morning in the Times, was: “I don’t think the district attorney would want to go into this investigation right now because it would hurt my opponent, in my opinion, if the facts came out.”

Younger did not, in fact, impede a probe. To the contrary, he had urged that a determination be made “as rapidly as possible” at the intake level.

Chief Deputy District Attorney Lynn D. “Buck” Compton released a May 2 letter Younger had sent the grand jury’s foreman. In it, the DA reports that he had discussed Yorty’s request with the Los Angeles Superior Court’s presiding judge, Joseph A. Wapner (who later presided on TV’s “People’s Court”) and the supervising judge of the criminal courts, William B.Keene (later the judge on “Divorce Court.”) The letter says:

“I informed them, in substance, it was my considered opinion that this matter should immediately be presented to the criminal complaints committee of the Grand Jury for determination and that my office would provide whatever witnesses the committee deemed appropriate.

“However, both Judge Wapner and Judge Keene informed me that because of the impending mayorality election, they deem it inappropriate for the criminal complaints committee of the Grand Jury to conduct an inquiry into this matter at this time. I am informed the judges will so notify you.

“I share the concern of these judges that the Grand Jury may be used for political purposes. However, inaction by the committee may equally be used by one of the candidates. Therefore, it is my view that the criminal complaints committee of the Grand Jury should, as rapidly as possible, make a decision on Mayor Yorty’s request.”

The grand jury took the judges’ advice to hold off on any action until after the election.

![]()

Yorty won that election. Nothing more was to be heard of the supposed $1,000 bribe.

In January, 1970, Younger was a declared candidate for the Republican nomination for state attorney general. Yorty pondered entering the contest for the Democratic nod for that office. If he had done so, it’s likely that he would have won it, having superior name recognition to the man who did bag the nomination, Chief Deputy Attorney General Charles O’Brien.

A Younger-Yorty battle would have been a lively one.

As it turned out, Yorty sought his party’s nomination for governor, losing to former Assembly Speaker Jesse Unruh, who lost to incumbent Ronald Reagan.

The mayor did what he could to thwart Younger’s bid for the AG’s post. I’ll discuss the 1970 contest in a future column. But next time, I’ll look at Younger’s action in removing Aaron Stovitz as the lead prosecutor in the Charles Manson murder case.

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOOTNOTE: My conversation with Eric Younger took place last week. He was on the deck of a cruise ship in Norway. I regret to say I wasn’t there, also; we talked by telephone.

His father’s victory celebration on election eve in 1968 was “very modest,” he recalls, with less than 40 persons gathered at the Athletic Club. In light of the certainty of the win, the former jurist notes, there was hardly a need for a “cast of thousands.” (There were 1,410,374 votes for Younger and 410,555 for Hannon, a Peace and Freedom Party activist who was campaigning on a platform of legalizing marijuana.)

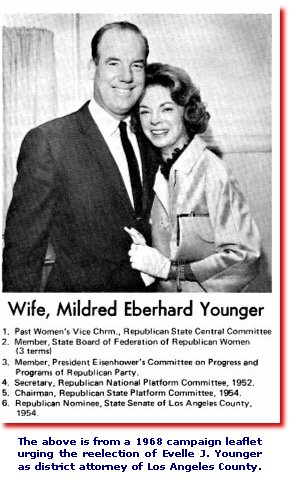

With respect to a friendship between his father and Yorty, Eric Younger says the real tie was between his mother, Mildred Younger, and the mayor.

Mildred Younger, a prominent radio and television commentator, was once seen as a Republican with considerable

potential in partisan politics. In 1954, she barely lost the Los Angeles seat

in the state Senate to Democrat Richard Richards…the same election in which the

Democratic nominee for the U.S. Senate, Yorty, lost to Republican Thomas Kuchel.

Mildred Younger, a prominent radio and television commentator, was once seen as a Republican with considerable

potential in partisan politics. In 1954, she barely lost the Los Angeles seat

in the state Senate to Democrat Richard Richards…the same election in which the

Democratic nominee for the U.S. Senate, Yorty, lost to Republican Thomas Kuchel.

The articulate Mildred Younger might well have gone far in politics had it not been for a freak effect of a car accident: the loss of her voice.

Yorty appointed her to the Board of Administration of the City Retirement System, to the city Board of Library Commissioners, later to the Community Redevelopment Agency. I remember covering meetings of the Library Commission for the Herald-Examiner in 1971. She could speak, at that point, but through a “voice box,” a contrivance that caused her artificial-sounding utterances to resemble those now associated with computers. In 1975, through surgery, her voice was restored, after a 17-year incapacity.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company