Wednesday, August 6, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Office of District Attorney Shines During Evelle Younger Years

By ROGER M. GRACE

Sixty-Seventh in a Series

EVELLE J. YOUNGER was sworn in as the 35th district attorney of Los Angeles County on Dec. 7, 1964, and between then and his departure from the office on Jan. 4, 1971 when he became state attorney general, he fashioned the office into one that was marked by efficiency, professionalism, and esprit de corps.

Talk to those who were involved in the criminal justice system then. One after another will speak of Younger in the most laudatory of terms…and many will add reference to the high caliber of his lieutenants.

Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Stephen S. Trott, who was chief deputy under a later DA, John Van de Kamp, recalls:

“I drove across the country from Harvard in 1965 to join the LA DA’s Office because I heard great things about Evelle, and they were all true. He was a great administrator who had a keen talent for picking the right people for the right positions, such as Buck for chief deputy, Bill Ritzi for assistant DA, Joe Busch, and Dick Hecht for special assignments.”

“Buck” is the nickname of Lynn D. Compton, a World War II hero, former police officer, and future Court of Appeal justice. He appears to warrant major credit for the success of Younger’s administration. Compton was appointed to the No. 2 post two years to the day after Younger took office, and was the third person to whom Younger entrusted that job. His initial chief deputy was, atypically, brought in from outside the office: criminal defense lawyer Earl C. Broady, a one-time janitor and the first African American in the history of the DA’s Office to hold a top management position. Broady left when he was appointed to the Los Angeles Superior Court in 1965, and was succeeded by erstwhile criminal defense attorney Harold Ackerman, who departed when he was placed on the Los Angeles Municipal Court in 1966 (gaining election to the Superior Court two years later).

William L. Ritzi was given the office’s No. 3 spot as assistant district attorney on Dec. 7, 1966, the same day Compton left that position to become chief deputy. Compton had been the assistant DA since July 7, 1965 (his first assignment under Younger being that of head of branch court operations). In 1969, Ritzi was appointed to the county’s upper trial bench.

Joseph P. Busch Jr. was designated chief deputy on June 22, 1970, taking over from Compton, who had been appointed to Div. Two of this district’s Court of Appeal. Younger, at the time, was in a run-off for attorney general, and publicly said that if he won, he would recommend that the Board of Supervisors choose Busch to replace him. Younger did win, and Busch got the job.

Richard W. Hecht was picked by Younger to head the newly created Civil Intelligence and Organized-Crime Unit. After Younger’s tenure as DA, Hecht became director of the Bureau of Special Operations.

![]()

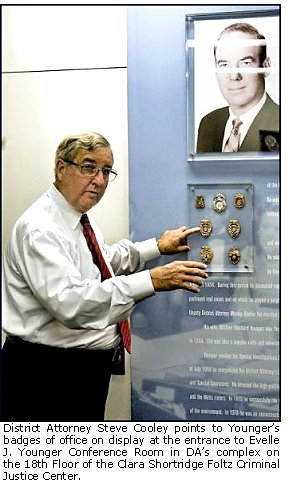

The current district attorney, Steve Cooley, tells me that

Younger—“along with people advising him, like Buck Compton”—can be said to have

probably done more “in the last 50 years” than anyone  else “to reorganize the

office and professionalize it.” He adds:

else “to reorganize the

office and professionalize it.” He adds:

“The current organizational chart you see, where it is broken up into special divisions rather than line operations—that was really their concept. And they expanded the number of branch offices throughout the county significantly during that time frame.”

Cooley says, in essence, that Younger was his role model. The DA (whose wife, Jana, is a second cousin of Younger) observes that Younger “saw certain needs for the county, for the justice system, law enforcement, the office,…and he figured out a way to get it done.”

Office manuals, he notes, were introduced when Younger was DA, and it was Compton who drafted them.

Compton, now in retirement in the State of Washington, discloses that he didn’t have “any problem selling” Younger on the need for the manuals…a need he says he had spotted based on his studies in business management. He relates that he and Younger “saw eye to eye on a lot of stuff.”

The former jurist reflects that the office had been “totally disorganized” before Younger headed it, but doesn’t pin the blame on his immediate predecessor, William B. McKesson, in particular, saying that the mess “went back years.” He explains that the “office had grown up without any kind of management,” and offers the observation that “lawyers are always reluctant to have any organization or supervision.”

Retired criminal defense attorney Paul Geragos, who joined the office when McKesson was DA, recalls:

“It was not much of an office when I got there.”

He says Younger “really brought the DA’s Office into the 20th Century,” adding:

“He brought a great deal of discipline and organization to what was theretofore not a well-organized office.”

![]()

With the influx of population in Los Angeles County, Cooley says, court operations necessarily expanded, and with it the DA’s office—so, Younger had the task of large-scale hiring.

Wilber M. Sweeters, who was drafting appellate briefs for the office then, recalls the hiring efforts. He says of Younger—whom he terms a “very excellent” DA:

“One of his strengths was recruiting DAs. He used to travel to the east to recruit people from the best law schools.”

He notes that Younger was not a micro-manager—nor, he says, was Compton. Sweeters had an office right next to Compton’s, he brings to mind, and says: “He was very easy to get along with,” adding:

“He made sure everybody knew what he was supposed to do. He was somebody you felt you could trust.”

![]()

Richard Hirsch, a leading criminal defense lawyer who began his career in criminal law as a deputy DA under Younger, describes the caliber of upper management in the office when he joined in 1967 as “amazing.” He notes that Compton was then chief deputy, terming him “one of the strongest guys ever in the DA’s Office,” and also mentions, with admiration, Ritzi and Busch.

Younger, he says, “surrounded himself with good people and he let them make decisions,” giving latitude to those in upper management…and also, to a greater extent than now exists, to lower troops.

Hirsch, who was 1980 president of the Criminal Courts Bar Assn. and in 2003 received the group’s Career Achievement Award, says that Compton “hated pornography” and recounts that an “Obscenity Division of the DA’s Office” was set up, which was “Buck’s baby.” Hirsch well remembers that; he was picked to head the division.

The lawyer relates that Compton, who became a prosecutor in 1951, was “a legend within the office” who was “incredibly well respected,” “had tremendous power and control in that office,” and that “[i]f he wanted something, it happened.”

He labels Ritzi “a sweetheart,” calling him “one of the kindest, most wonderful men you could ever hope to encounter,” adding: “he was that way as a judge, and he was that way as a [deputy] DA.”

Busch also possessed the same qualities, he says.

In those days, the deputies, whom he reckons numbered about 150-160, took “great pride” in being with the office, and there was “a lot of camaraderie” among them, he comments.

Others share that recollection. Trott says of Younger:

“He made you proud to be a part of that office.”

Michael Marcus, a current member of the State Bar Board of Governors and a former State Bar Court judge, was a deputy in the office then. In the units that he was in, he says, “there was a lot of esprit de corps.” He goes on to say, with respect to the lawyers in the office:

“Back then, we were a pretty happy group.”

Sweeters likewise remembers that there was no “spirit of dissention” in the office then.

That surely could not be said as to the later administrations of Ira Reiner or Gil Garcetti.

![]()

Hirsch had worked in 1966 in the reelection campaign of Democratic Gov. Pat Brown. He notes that Younger was “a Republican, and a pretty avid Republican politician, and I just came off a Democratic campaign for governor as an aide.” Yet, when he sought employment as a deputy DA in 1967, “nobody asked what my party affiliation was or what my political proclivities were,” Hirsch points out.

In fact, he says, when he was interviewed for the position by Busch, he was queried if there were anything else that should be known about him that hadn’t come out, and volunteered that he was opposed to the death penalty. Hirsch relates:

“I thought that was going to be the end for me.”

To the contrary, he says, Busch assured him:

“Don’t worry about it. We got lots of guys who will ask for the death penalty.”

Hirsch, of the Santa Monica law firm of Nasatir, Hirsch, Podberesky and Genego, declares:

“That showed me what kind of office it was at the time. They accepted all political stripes and all philosophies.”

As Trott remembers it, Younger “ran the place as if politics didn’t exist.” To Younger, he says, “the law, the facts, the circumstances, justice” were what counted—“not politics.” He mentions that “most prosecuting attorneys’ offices were very political” at the time.

![]()

One person who says that she has “the highest regard” for Younger had been involved in activities of the liberal wing of the Democratic Party before ascending to the bench. Vaino Spencer, who recently retired, was a Los Angeles Municipal Court judge when Younger was DA, and ultimately became presiding justice of Div. One of this district’s Court of Appeal.

Younger was like a “breath of fresh air,” she remarks, crediting him with uplifting the professional standards of lawyers in the office. While his predecessor, McKesson, was DA, Spencer says, deputies would “get hysterical” if a judge ruled against them…they would “throw down their pencil,” and otherwise behave like “kindergarten children.”

The appearance, Spencer says, was that they would “get demerits in their office” if the judge ruled for the defense.

She also faults McKesson for widespread blanket-affidaviting of judges (disqualifying them routinely through declarations under penalty of perjury that asserted them to be biased). Spencer notes that she was not personally the target of such an office policy under McKesson—though one close friend of hers, Judge Robert Fainer, was.

The retired jurist recounts that Younger on one occasion came into her courtroom “and sat in the back.” It may be inferred that he approved of her performance because, Spencer says, he “never permitted any of his deputies to recuse me.”

Warren Ettinger was active in the Democratic Party prior to his appointment to the Pasadena Municipal Court by Gov. Pat Brown in December, 1966.

Ettinger, who is serving on assignment to the Los Angeles Superior Court, says that Younger and Brown “took a liking to each other” and would confer. When Brown was contemplating judicial appointments in Los Angeles County, Ettinger relates, “Pat would run them through Evelle” on a confidential basis, despite being members of opposing parties.

He says of Younger:

“I really liked him and I trusted him.”

The 1966 Criminal Courts Bar Assn. president adds:

“It would be difficult to find anyone who would say a bad word about him”

![]()

The DA’s Office, while Younger led it, was a Camelot…but it was not a realm without thunderstorms.

Younger did battle with Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty and local TV’s leading newscaster, George Putnam. In the aftermath of the Watts riots, he faced the prospect of further unrest following the fatal police shooting of a black motorist who was speeding because he was rushing his wife, about to give birth, to the hospital. He handled the prosecution of infamous slayer Charles Manson…and yanked a popular deputy from that case for talking too much with reporters. He sought reforms; some evoked controversy.

Challenges Younger faced will be dealt with in future columns.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company