Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

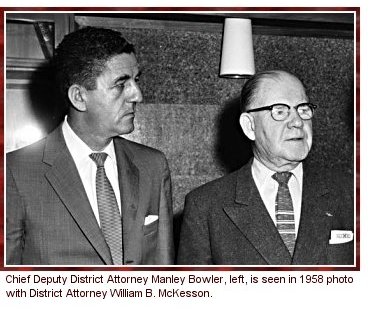

McKesson in 1963 Seeks to Assure 1964 Election of Bowler…and Derail Younger’s Candidacy

By ROGER M. GRACE

Sixty-Fourth in a Series

WILLIAM B. McKESSON was district attorney. EVELLE J. YOUNGER wanted to be.

Younger, a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court, made it known in early 1963 that he would be a candidate for DA in the next year’s election. It might be that Younger’s stated intention prompted McKesson’s July 24, 1963 announcement that he would not seek reelection….or maybe McKesson, who would have been 69 when the next term commenced in December, 1964, would have stayed out of the race, in any event.

What is clear is that McKesson became a vigorous partisan in the political campaign of the man he wanted to succeed him: his chief deputy, Manley Bowler.

Although McKesson’s announcement came six months before the filing period for the office opened, it was known even then that Bowler would likely face opposition not only from Younger but from a second Los Angeles Superior Court judge, Vincent Dalsimer (who was later to serve as a justice of the Court of Appeal).

The public’s regard for McKesson had dipped the previous year when he ran for the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor and lobbed charges against the incumbent, Glenn Anderson, of ties to mobsters…charges which he couldn’t back up. McKesson’s image plunged further during the course of his assaults in 1963 on the two judges, with Younger being his primary target.

![]()

At a press conference on July 24, McKesson rendered his endorsement of Bowler, hailing the prosecutor of more than 22 years as “a man who has proven he has integrity, experience, and the ability to serve as district attorney better than any other possible candidate.”

The press conference had been set for the following day. However, a Page One article on July 24 in an early edition of the evening Herald-Examiner, bearing the byline of the paper’s feisty political editor, Jud Baker, reveals what McKesson would be announcing. With other news outlets wanting comment, reporters were hastily summoned by McKesson that same day.

The Herald-Examiner’s July 25 report quotes McKesson as telling reporters:

“I’m most concerned that the office of district attorney not fall into the hands of some political hack. I don’t want anyone to become district attorney and use the office as a steeping stone to a higher office.”

A reporter asked if he had not attempted to usethe office as a stepping stone to the post of lieutenant governor the yearbefore, prompting the non-responsive response:

A reporter asked if he had not attempted to usethe office as a stepping stone to the post of lieutenant governor the yearbefore, prompting the non-responsive response:

“No, I ran for lieutenant governor because I thought California needed a new and better lieutenant governor.”

McKesson’s reference to a “political hack” was understood to refer to Younger—not because he was, but because of what McKesson also said. As the Times’ July 25 story recounts it:

“[H]e declined to name the aspirant he had in mind. But he followed up by saying that both Younger and his wife have long experience in Republican Party affairs. Mrs. [Mildred] Younger was the GOP nominee for state senator in 1954” (losing to Richard Richards).

The term “political hack” connotes a “machine politician.” Did that fairly describe Younger? No. Although Younger had been a chairman of the Republican County Central Committee in 1950-51, he’d been on the bench, first as a Municipal Court judge, since 1953. While on the lower trial court, and since ascending to the Superior Court in 1958, he was divorced from partisan politics.

![]()

On July 30, McKesson’s lambasted Younger—and, in an almost parenthetical manner, Dalsimer—for running for the DA’s post without first resigning from the bench. They were in blatant violation of a judicial canon of ethics, McKesson charged in a speech before the Los Angeles American Legion Luncheon Club.

He pointed to Canon 30 of the American Bar Assn.’s Canons of Judicial Ethics which provided:

“While holding a judicial position he [a judge] should not become an active candidate either at a party primary or at a general election for any office other than a judicial office. If a judge should decide to become a candidate for any office not judicial, he should resign in order that it cannot be said that he is using the power or prestige of his judicial position to promote his own candidacy or the success of his party.”

Canon 26 of the Conference of California Judges (now the California Judges Assn.) was to like effect, and seemingly more pertinent, but news reports do not mention any allusion to it by McKesson.

The DA said of Younger, according to the accounts:

“For the past year, he has been engaging in a course of conduct soliciting political support and financial contributions for his campaign from judges, lawyers and other citizens even though such conduct is expressly forbidden by the Canons of Judicial Ethics promulgated to set a standard for the entire judiciary of the nation by the American Bar Association.”

What McKesson didn’t mention was that the ABA’s guidelines had no binding effect anywhere, except in states where the supreme courts had adopted them—and that didn’t include California. (The Conference of California Judges’ canons also had no official status—and, in the preamble, were labeled as the organization’s “views” as to proper conduct.)

McKesson said of Younger and Dalsimer:

“Neither of them will hear any more criminal trials.”

They would be disqualified, he explained, through the filing of affidavits of prejudice.

In other words, he was declaring that he would require deputies in his office to commit perjury. There was no reason to suspect bias against the prosecution on the part of either of these judges based on their past performances, and they were surely not apt to develop pro-defense leanings at the very time they were seeking support for the post of the county’s chief prosecutor. Yet, McKesson wanted deputies to swear, falsely, that these two judges were biased against the People in order to facilitate his personal, petty, and purely political objective of discommoding rivals of his chosen successor.

![]()

The district attorney represented in the talk before the American Legion group that Younger “was found guilty of misconduct by the Los Angeles County Bar Assoc. in 1954, when he was violating the code governing conduct of judges in California by continuing to appear on a commercially sponsored traffic court TV program.”

McKesson mangled the facts. “Traffic Court” was not on the air in 1954; it debuted on June 2, 1957 on KABC-TV, as an unsponsored public service program. It became so popular that the Southern California Chevrolet Dealer Assn. became its sponsor. Younger was then a member of the Municipal Court, and the Los Angeles County Bar Assn. Board of Trustees on Dec. 12, 1957, did pass a resolution calling into question the propriety of his continuing to appear on the program in light of its commercial nature. Younger was hardly “found guilty” of anything, however; that slanted phraseology implied, falsely, that the bar group possessed adjudicative powers.

Younger queried the Conference of California Judges on the matter, and a 15-member committee was appointed to provide an advisory opinion, with Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Mildred L. Lillie (later a presiding justice of the Court of Appeal), heading the panel. Its opinion, released on Feb. 6, 1958, says that Canon 21 “clearly denounces a judge’s participation in any ‘commercially sponsored advertising program,’ ” and that an exception should not be engrafted onto it.

Younger publicly responded:

“I believe the program was proper and important from the standpoint of traffic safety. I think it was the most effective means for traffic safety education ever devised.

“I asked for the opinion and I will abide by it. I am not bound by the opinion, but I want to do what the members of my profession think is proper.”

Younger left the program, being replaced by UCLA Law Prof. Edgar Allan Jones Jr.

This does not strike me as a reflection of any ethical deficiency on the part of Younger…but the allegation by McKesson does say much about that DA’s ethical standards in the context of political campaigns. Those standards weren’t tested in 1958; no one ran against him. They were barely tested in 1960; his opposition was weak. Two years after that, in running for lieutenant governor, he showed himself to be willing to sling charges without proof. And in 1963, he was again engaging in smear tactics.

![]()

Were Younger and Dalsimer ethically obliged to resign?

The mere existence then of Canon 30 and the CCJ’s mirror provision does not mandate a response in the affirmative—after all, the canons were non-binding on California judges. The salient factors are that Canon 30 was contrary to the practice in this state, and lacking in public support.

ABA Canon 30 went into effect in 1937. In 1946, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Goodwin J. Knight ran for the post of lieutenant governor, and was elected to it. He had not resigned as a judge before his election, and there was no controversy over that. Knight, a Republican, subsequently became governor in 1953 when Gov. Earl Warren was appointed chief justice of the United States, and Knight was elected in 1954 as the candidate of both the Republican and Democratic parties, under cross-filing.

Then, in 1954, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Frederick F. Houser sought the nominations of his own Republican Party as well as the Democratic Party for lieutenant governor, a post he held during Warren’s first term as governor. He did not doff his robe before undertaking the venture, and no controversy was engendered by that. He lost.

In 1958, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Stanley Mosk ran as a Democrat for the post of attorney general. During the run-off, the GOP candidate, U.S. Rep. Pat Hillings of Los Angeles, did make a fuss over Mosk having retained his judicial post, but to no avail. The public discerned no problem. (The future California Supreme Court justice had waived his pay during the period of his absence from the bench while off campaigning…which later became, and still is, a statutory requirement for judges while seeking nonjudicial offices.)

The month after Mosk was elected as AG, the Los Angeles County Bar Assn.’s Board of Trustees passed a resolution reading: “It is improper for a judge to become a candidate for election to non-judicial office judicial position, or for a judge to engage in a partisan political activity.” Although the then-stodgy bar group was apparently upset over Mosk having retained his judicial office while running for attorney general, the public wasn’t. As a Dec. 24 editorial in the Long Beach Press-Telegram observes: “Since [Mosk] was elected attorney general of California by a larger margin than any other office seeker, the public apparently was unprejudiced by his alleged violations of canon.” The editorial adds that the canon “would seem to create an unnecessary encumbrance at judicial rank for good men who wish to advance.”

It’s telling that when Mosk was actively seeking a nonjudicial post without relinquishing his judgeship, McKesson was out there campaigning for him, uttering not a single word of disapproval over the non-resignation. But when Younger and Dalsimer were merely testing the waters as would-be candidates, McKesson was quick to denounce them.

![]()

In 1960, Adolph Alexander was McKesson’s election challenger. He went on a leave of absence as a member of the Beverly Hills Municipal Court, but did not relinquish his judgeship, despite McKesson’s call for him to do so.

Mosk’s 1962 Republican challenger was Mariposa Superior Court Judge Thomas Coakley, a one-time big-band leader. During the primary, LACBA called upon Coakley to resign. A March 17 article in the Times relates that the judge responded in a letter to County Bar President Walter Ely (later a judge of the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals) that he had been “prepared to resign” but that leading members of the bar had advised him that doing so would not be in the “public interest.” The article says that Ely, in a return missive to Coakley, acknowledged that while the “bar as a whole” did not support LACBA’s position, the judges did, as evidenced by their adoption of the ABA canon.

In later years, the subject of that 1962 campaign having come up in conversation, I told Mosk that the rear bumper of my first car, a red jalopy which I drove in my senior year in high school, was emblazoned from end to end with GOP bumper strips, including one supporting Coakley. He told me that I was forgiven, the “statute of limitations” on my indiscretion having expired.

Knight, Houser, Mosk and Coakley ran in partisan political races, and obviously did not bring the judiciary into disrepute by having done so without first giving up their judgeships. Younger and Dalsimer were readying to run for a nonpartisan post, rendering the canons lacking in purpose.

![]()

California judges did not long cling to the ABA’s view, a view the ABA was, itself, to abandon.

McKesson’s slap at Younger and Dalsimer would evoke retorts by those candidates-to-be. The presiding judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court would get involved in the fray. Newspapers in the county would back the judges.

McKesson’s July 30, 1963 speech was, overall, to prove a major boner by the district attorney.

Details on this, and further developments in the contest, are to come in the next column.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company