Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

McKesson Runs for Lieutenant Governor, Portrays Incumbent as Linked to Criminal Element

By ROGER M. GRACE

Sixty-Third in a Series

WILLIAM B. McKESSON, district attorney of Los Angeles County, must have known that if he didn’t seek higher office in 1962, he might as well abandon the idea of doing so. He would be 67 on June 24 of that year. The question was which race he should enter.

He wanted to become state attorney general, and some had envisioned his running for that office in 1958. A Los Angeles Times story of Aug 15, 1957 reports that the president of the powerful California Democratic Council, Alan Cranston—later to become a U.S. senator—mentioned McKesson as a possible AG contender. That was assuming that the incumbent, Democrat Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, sought his party’s nod in the gubernatorial race or the contest for the U.S. Senate rather than running for reelection.

However, the Times’ issue the next day quotes McKesson as saying:

“I have no intention or inclination to seek any State or other political office other than the one I am holding.”

To do otherwise would have meant giving up what amounted to a “safe seat.” District Attorney S. Ernest Roll had been elected without opposition to a new four-year term that began in December, 1956, but died in October; the Board of Supervisors appointed McKesson to fill the vacancy, but the election law required that McKesson come before voters in 1958 if he wanted to stay in office for the final two years of Roll’s term. Although McKesson did continue to toy with the idea of seeking a higher position, he took the cautious route and, like Roll, ran unopposed.

Brown attained the governorship and fellow Democrat Stanley Mosk, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, was elected attorney general.

McKesson incurred surgery and suffered a stroke in early 1961, but rebounded, with his political future, if any, to be unimpaired by concerns over his health.

![]()

An Aug. 23, 1961 column by Times political analyst James Bassett (later associate editor of the newspaper) says that “Civic Center was buzzing this week with reports that Dist. Atty. William B. McKesson would be amenable to appointment to Atty. Gen. Stanley Mosk’s post if the latter moves up to the State Supreme Court.” The column quotes McKesson as saying: “As a public lawyer, I would naturally be interested if the attorney general’s office became vacant.”

However, Brown on Dec. 6, 1962 named Court of Appeal Justice Paul Peek to the vacancy for which Mosk had been in contention…a vacancy which might well have gone to Mosk had the prospect of the appointment not been caught up in a controversy over supposed political promises. The head of the Department of Motor Vehicles, Robert McCarthy, had heatedly resigned—labelling Brown’s administration “spineless”—upon learning he would not be appointed attorney general, as he had anticipated, upon Mosk’s expected placement on the high court. (Mosk’s appointment to that tribunal would not come until 1964.)

There were reports in 1961 that Mosk was eyeing the upcoming race for the U.S. Senate, which would have afforded McKesson a clear path to run for attorney general. But Mosk announced on Jan. 3, 1962 that he was seeking reelection to his present post.

With Mosk in the race, the office McKesson coveted was off limits. Mosk was, virtually, politically invincible. Reflecting that is the fact that no one challenged him in the Democratic primary. Besides, McKesson was an admirer of Mosk. He had campaigned so hard for his fellow Democrat in 1958 that the Times scored the DA in an Aug. 8 editorial for violating “the spirit, at least, of his nonpartisan status and obligations.”

![]()

A Jan. 6, 1962, report by Bassett quotes McKesson as saying that he was “seriously considering” a try for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate in light of “overtures” to him by “a number of party leaders” and that he would decide “within the next two weeks.”

For whatever reason, McKesson shied away from that race, with state Sen. Richard Richards capturing the nomination and losing to the Republican incumbent, Thomas Kuchel.

Four years earlier, Cranston had listed McKesson not only as a possible candidate for attorney general, but as one of four viable Democratic contenders for governor if Brown did not run. As it stood in 1962, the governorship could not be wrested from the popular Brown—as former Vice President Richard Nixon learned that year in the general election.

That left McKesson with four state constitutional offices: lieutenant governor, controller, secretary of state, or treasurer. Only one would be a step up.

![]()

The lieutenant governor was Glenn Anderson, who was nondescript—or if he to be were to be described, the word “doofus” might well come to mind. McKesson evidently thought he could topple the seemingly lightweight incumbent in the Democratic primary. His undertaking was bold…and naïve.

When Anderson, a former assemblyman from Hawthorne, declared that he would be a candidate for lieutenant governor in the 1958 Democratic primary, McKesson was seen as a possible rival for that post, too. The Nov. 14, 1957 issue of the Fresno Bee quotes Democratic State Chairman Roger Kent as pointing to McKesson, Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge William A. Munnell and Assembyman Julian Beck, D-Los Angeles, as other prospective entrants in the contest. (Beck and Munnell both became members of the Los Angeles Superior Court.) The Long Beach Press-Telegram’s edition of Jan. 5, 1958 contains mention that McKesson was among those who would be seeking the California Democratic Council’s endorsement for lieutenant governor at its conclave the next weekend.

But now, in 1962, Anderson had the advantage of incumbency…and the party machinery was behind him. Brown, a moderate Democrat who reportedly would have preferred McKesson, also a moderate, as his running mate in 1958 over the extreme-liberal Anderson, now backed the incumbent lieutenant governor “100 percent.” McKesson staged a desperate, if not pathetic, campaign.

![]()

In taking out nominating papers on March 28, McKesson issued this statement:

“The suggestion has been made to me there are criminal influences who would like to support Anderson that want to get a foothold in the state and as a prosecutor I am interested in keeping the criminal element out of state government.

“I did not say he is aligned with a criminal element but I want to make sure they do not get a toehold.

“California is a lush field and I have devoted my energies in the last five years in combatting crime and this is one more step in that scrap.

“I think there are those engaged in criminal activities who are prone to think they could use him.”

Clearly, McKesson was seeking to link Anderson in the public’s mind with the criminal element, impliedly relying on inside information known to him because of his status as head of a prosecutorial office. Yet, what he actually said was that it had been suggested that the bad guys would like to support Anderson and attempt to influence him. He did not even state who had done the suggesting. McKesson did much in the way of hinting, nothing by way of particularizing, let alone substantiating.

Anderson’s response was that McKesson “has a perfect right to run for any public office he wants to but he also has an obligation, particularly as a public official, not to make slick, irresponsible charges which seem to mean something that he doesn’t dare say.”

An opinion column by Times political writer Carl Greenberg, published April 5, observes:

“[T]he district attorney is now confronted with producing the evidence and convincing the jury—namely the electorate—that he’s got a case against Anderson.

“Otherwise, McKesson falls on his political face.”

In the end, McKesson fell on his political face.

![]()

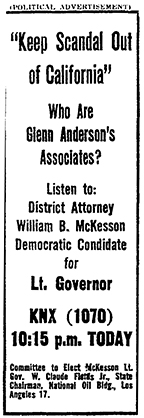

There was a grand build-up to McKesson’s promised revelations tying Anderson to underworld figures.

In a Friday, May 25, paid radio broadcast, McKesson boasted that he had “documented evidence” of Anderson’s “questionable associations.” He pledged to “reveal some of the specific facts” in a future radio speech.

An Associated Press dispatch of Monday, May 28, reads:

“District Attorney William B. McKesson, seeking the Democratic bid for lieutenant governor, is being guarded because of what his aides term possible reprisal over disclosures he plans to make.

“He normally is accompanied by an armed investigator. He has been assigned supplemental protection, officials said.

“McKesson has threatened to publicly name asserted questionable associations of Lieutenant Governor Glenn Anderson, whose position he seeks.

“He has promised to make further statement on the matter in a Tuesday night statewide radio broadcast.

“James Bigler, chief of the attorney general’s bureau of investigation, said that he ordered the extra guard for McKesson, explaining: ‘We are protecting him against any form of reprisal.”

In the Tuesday night broadcast, heard locally over KNX, McKesson charged that Anderson was a chum of one Andrew Lococo, who ran a restaurant in Hawthorne called “the Cockatoo,” and who had a police record.

The candidate said that he had a sworn

statement—the affiant being unnamed by him—that Lococo

on one occasion said to his brother, Nick Lococo,

with reference to Anderson:

The candidate said that he had a sworn

statement—the affiant being unnamed by him—that Lococo

on one occasion said to his brother, Nick Lococo,

with reference to Anderson:

“When I tell Glenn to jump, he better jump. I put him where he is.”

Lococo, as the story went, had a friend whose driver’s license had been revoked because of drunk driving; he had made known that he wanted Anderson to get the license reinstated; he became irate when he found out the lieutenant governor had not attended to the matter, prompting the remark to his brother.

McKesson disclosed that Lococo had been convicted in Milwaukee of larceny in 1940, at the age of 20.

The Times’ May 30 report quotes Anderson as saying:

“I have known Andrew Lococo for some time as a respected and responsible businessman in my home town of Hawthorne. I was, of course, aware that he had been in difficulty while still a young man more than 20 years ago before coming to California.

“So far as I know this man has rehabilitated himsef and is now a good citizen, a successful businessman and a leader of his church and community.

“I think it is cruel and despicable to drag this man’s name through the mud in an effort to smear me. Mr. Lococo is not running for office. I am.”

The Times article adds:

“Anderson said he often eats at the Cockatoo, but it also has as regular customers the Rotarians, Kiwanis, Junior Catholic League and Richard Nixon, among others.”

McKesson’s assault was feeble; the rejoinder was hearty.

In a Wednesday night broadcast, McKesson harped at the same theme. He charged that Anderson had “close friends who are well known criminals.”

When the Cockatoo burned down in 1958, he revealed, Lococo obtained a $220,000 loan to rebuild it. Given that the location of the property was in Hawthorne, it does not seem startling that the loan was made by Hawthorne Savings and Loan Association. But McKesson sought to use this as evidence of Anderson’s close ties to Lococo, pointing out that Anderson (a former mayor of Hawthorne) was a director of the S&L.

The statewide tally was 1,644,679 votes for Anderson, 367,515 for McKesson, with a minor candidate pulling 65,727.

McKesson opted not to seek reelection in 1964. But he was a spirited partisan of one of the candidates: his chief deputy, Manley Bowler.

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOOTNOTE: While McKesson failed sadly in attempting to show that Lococo was a crook, the fact is that he was. Lococo came to be identified on the U.S. attorney general’s 1970 list of major organized crime figures as a Mafia chieftan. He was convicted that year of perjury in connection with testimony before a federal grand jury probe of gambling and race fixing, a conviction which the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the following year.

This does not, of course, demonstrate that Anderson had any inkling of Lococo’s relationship to organized crime. Lococo was regarded as a local businessman...nothing else. Lococo ran, unsuccessfully, for the Hawthorne City Council in 1968, with the public being oblivious to his mob connection.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company