Wednesday, February 20, 2008

Page 15

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

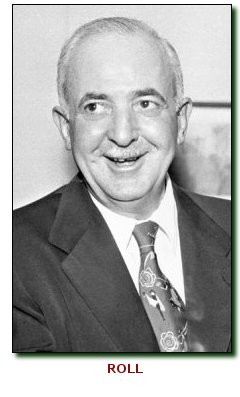

District Attorney Roll Has Skirmishes With Police Chief Parker, Others

By ROGER M. GRACE

Sixtieth in a Series

S. ERNEST ROLL was surely not among the most controversial of Los Angeles County district attorneys. But he did engage in a squabble with the City of L.A.’s chief of police, William H. Parker, and was involved in some other frays.

The first assault on Roll from another pubic official came when a member of the Los Angeles City Board of Education called for the district attorney’s ouster. This happened shortly after Roll was appointed in 1951. J. Paul Elliott accused the DA of “willful misconduct and illegal political activities.”

Elliott did have an axe to grind. Indicted by the grand

jury, he was himself facing trial on a charge of misconduct in office, the

penalty being, upon a conviction, removal as a member of the board. Three other

members had also been indicted, one of them on a felony charge.

been indicted, one of them on a felony charge.

It was alleged that Elliott had voted to grant bus contracts to the Landier Management Company even though he was a lawyer for the company, and was being paid a $200-a-month retainer.

In a statement before the board, as reported in the Los Angeles Times on Oct. 19, Elliott asserted that Roll “unfairly and unlawfully deprived those accused of an unprejudiced hearing and a fair court trial by instigating sensational charges in the press.” Elliott insisted that Roll’s public statements on the case had resulted “in an orgy of attack and recrimination, impugning the character and integrity of school officials,” adding:

“[F]or a District Attorney to seek an accusation or indictment under circumstances not adjudicated by the courts or expressly provided by the statutes as a violation of law is misconduct in office.”

Elliott called upon state Attorney General Edmund G. Brown to investigate Roll’s actions. Brown’s chief deputy in Los Angeles, William V. O’Connor, publicly stated on Oct. 19 that the attorney general would oblige. The next day, however, the AG contradicted that statement, saying, as a Times story recounts:

“I, as the Attorney General, have complete confidence in Ernie Roll and have not the slightest intention in the world of interfering in any degree whatsoever.

“If Elliott believes he should have redress, he should take it up with the presiding judge in charge of the grand jury and not take it up with the Attorney General’s office.”

Notwithstanding that flat-out statement, Brown, the day after that (following a telephone conversation with Elliott) instructed O’Connor to talk with Roll and with the judge in charge of the grand jury about the allegations. O’Connor quickly determined that nothing occurred out of the ordinary...that after witnesses testified before the grand jury, they were often interviewed by waiting reporters, and that some witnesses came prepared with news releases.

On Oct. 24, Brown released a statement saying:

“After a thorough investigation of the matter I find no evidence of misconduct in office on the part of Dist. Atty. Roll....

“In truth and in fact, Dist. Atty. Roll and his aides are to be commended for the thorough and efficient manner in which they have presented the case against the several members of the Board of Education. It is my opinion that Mr. Elliott’s charges are unwarranted.”

Those charges were also investigated by the Los Angeles County Grand Jury which took no action against the DA.

Elliott was convicted on March 6, 1952, and the Court of Appeal affirmed in an opinion by Justice Marshall McComb (later a member of the state Supreme Court).

![]()

Roll also took some heat in connection with liquor scandals of the mid-1950s.

First, putting those scandals in perspective….

The Los Angeles Mirror revealed in a series of articles starting in 1953 that the way to get a liquor license in those days was by greasing the palms of officials. The afternoon newspaper, owned by proprietors of the morning Times, cast the spotlight on the state Board of Equalization member from Los Angeles, Frank G. Bonelli, as a chief recipient of payoffs. The board at that time issued the licenses. Bonelli, an assemblyman from 1931-1933, and an unsuccessful candidate for district attorney in 1940, was defeated for reelection to the board in November, 1954 in light of the Mirror’s exposes. As the investigations advanced, Bonelli fled to Mexico, where he died in 1970. (At that same 1954 election, on a statewide basis, Prop. 3—robustly promoted by Gov. Goodwin J. Knight—was passed by voters, creating the Alcohol Beverage Control which would, effective Jan. 1, issue liquor licenses.)

One liquor-license broker, who had secured payoffs from license applicants and passed them on to those who arranged for the licenses, was an attorney and former Los Angeles Municipal Court judge (1927-30), Leonard E. Wilson. On Dec. 7, 1954, he committed suicide…but only after giving names and places to Brown’s investigators. Among those named by Wilson as being on the take was a former Los Angeles district attorney, Fred Howser, who allegedly took a $5,000 bribe in April, 1950, while serving as state attorney general.

Back to Roll. Assemblyman Charles Chapel, R-Inglewood, on Dec. 17, 1954 appeared before the Assembly Interim Committee on Elections and Reapportionment, of which he was not a member, and asked the panel to urge that Brown take over the probe in Los Angeles County because Roll wasn’t doing the job. He asserted that when he tried to communicate with Roll on the matter, he “got the brushoff.”

The Mirror’s edition that night quotes Chapel as declaring:

“I’ll take my chances with Brown even though he is a Democrat and I am a Republican.”

The lawmaker is also quoted as saying:

“The District Attorney’s office’s concern seems to be explaining to the public why matters cannot be considered by the [grand] jury.

“Make no mistake, we have corruption of government in Los Angeles County. How long are we going to wait before we uncover it?”

The Mirror was unable to secure a comment from Roll on Chapel’s allegations. Its article says:

“When a reporter tried to get Roll to comment on Chapel’s remarks, the D.A. refused to listen and said, ‘I’ll read it in the paper.’ ”

Roll did respond substantively to a Times reporter, however. The issue the next morning quotes him as saying:

“We have six men on those cases—two deputies and four investigators working with Brown’s men. When we have what we consider a good case we will file it in court, as we have already done, no matter whom it hits.”

In May of 1956, San Diego District Attorney Don Keller faulted Roll for failing to bring a prosecution against Bonelli over a payoff by the Ambassador Hotel to block suspension of its license. Roll’s response was that the statute of limitation had run on the alleged 1950 bribe before the matter had come to the attention of his office.

![]()

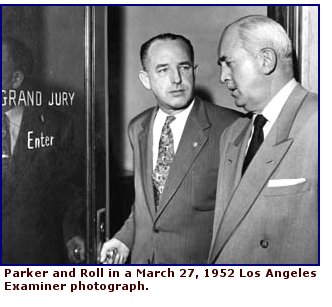

The DA’s wrangling with Parker is described in a 1958 book by the late actor Jack Webb, “The Badge: True and Terrifying Crime Stories That Could Not Be Presented.” Webb, who produced and starred in “Dragnet,” says:

“Temperamentally, Parker is not the man to submit quietly.

Largely on their contrary views about methods of obtaining evidence, the Chief

and his own district attorney, the late S. Ernest Roll, broke openly. Roll

wanted policemen to sign ‘rejection of complaint’ slips when the DA felt there

was no ground for prosecution. Parker ordered his men not to sign the slips,

and for a long time Los Angeles law enforcement went forward in a curious

atmosphere. Police and prosecutors were almost as cool to each other as both

were to criminals.”

“Temperamentally, Parker is not the man to submit quietly.

Largely on their contrary views about methods of obtaining evidence, the Chief

and his own district attorney, the late S. Ernest Roll, broke openly. Roll

wanted policemen to sign ‘rejection of complaint’ slips when the DA felt there

was no ground for prosecution. Parker ordered his men not to sign the slips,

and for a long time Los Angeles law enforcement went forward in a curious

atmosphere. Police and prosecutors were almost as cool to each other as both

were to criminals.”

The “contrary views about methods of obtaining evidence” centered on a clash over the California Supreme Court’s 1955 decision in People v. Cahan which barred admission of evidence obtained through illegal searches and seizures. Parker assailed the decision as handicapping police, and Roll expressed dismay that the police chief would sanction his officers employing unlawful methods of investigation.

While relations between Roll and Parker had been strained in the aftermath of that decision, feelings were soon to turn raw. Parker on April 19, 1956, publicly blamed the rising crime rate on Roll, charging that he “is disposing of one-half of the requests submitted to him for felony complaints without further action.”

Roll is quoted in the Times the following morning as saying:

“Chief Parker is in error, I might point out, when he cites figures purporting to be rejections of felony complaints by my office ‘without further action.’ It has always been the practice of my office to refer to the City Attorney’s office misdemeanor cases brought to my complaint division under the guise of felony cases. This represents a sizable number of the total number of arrests.”

The matter might well have died out had there not been a column in the Los Angeles Examiner on May 15 stoking the embers. The opinion piece by Lloyd Emerson, who covered the district attorney beat, says:

NEWEST RUSE in the fussing between District Attorney S. Ernest Roll and Chief of Police William H. Parker is Roll’s scheme to get Parker’s policemen to admit in writing that they make illegal arrests.

It is a neat project the D. A. has worked out, and his aidessay he is succeeding with it.

….

POLICE OFFICERS who appear at the District Attorney’s complaint division these days may find themselves signing documents in which they admit that they, or members of the department, are guilty of false arrests.

There is an agreement of long standing that when a deputy district attorney refuses a policeman’s request for a felony prosecution the policeman will indorse the deputy’s “rejection of complaint.”

The rejection is a formal report in which the deputy gives his reasons for not proceeding on the policeman’s evidence. Usually it states that the evidence is not sufficient.

After Parker’s latest blast, Roll’s complaint deputies were instructed to be vigilant for cases in which the policeman plainly had no reason to make felony arrests. They were advised to describe these in their formal rejections as “unlawful arrests” and to have the policemen endorse the reports as usual.

Deputies say that, while some officers refuse to sign, they are obtaining five or six such reports a week. These will serve to harass Chief Parker shortly.

The column concludes: “The next move seems to be up to Chief Parker when he reads this.”

He apparently did read it. The May 19 edition of the Examiner contains this declaration from the police chief, uttered the day before:

“This new practice of asking officers to sign rubber-stamp material at the District Attorney’s office goes beyond the bounds of propriety.

“It…lays the Police Department and its officers open to civil action.”

Parker ordered officers not to sign the forms.

The Examiner articles attributes to Roll a statement that a study of LAPD requests for felony complaints between January and April showed that “[a]pproximately 50 per cent of the cases involved fact situations where no felony had been committed in the first place or, finding a felony crime, there was no evidence to connect the suspect with the crime.”

The revised “rejection slips” to which Parker took exception now contained, following a deputy’s reasons for spurning a request for a felony complaint, a portion for the arresting officer to sign saying:

“I have read the above reasons for the rejecting of the complaint and concur in this disposition of the case. The information purporting to have been given by me to the Deputy District Attorney is correctly stated above.”

![]()

The attorney general reviled at the bickering. On May 21, Brown announced he would launch a six-month investigation of criminal justice procedures in Los Angeles County. In a statement, he said:

“The Attorney General’s office will try to take an impartial look at the constant quarreling between the District Attorney of Los Angeles County and the Chief of Police of Los Angeles.

“I feel that the situation is hurting the administration of justice in Los Angeles County.”

A May 23 editorial in the Examiner lauds Brown’s action, observing that the “quarrel between Mr. Roll and Chief Parker has reached serious and disturbing aspects” which “the public has already defined as deplorable.”

The controversy quickly simmered down. On May 25, Parker agreed in a “Dear Ernie” letter to allow officers to sign the slips acknowledging the accuracy of the recitation as to what evidence they provided, but eliminating, as Roll had proposed, the portion indicating the officer’s concurrence in the decision.

The state investigation nonetheless commenced in June. Despite Roll’s death on Oct. 26, 1956, a report was issued the next month. There had been no real “feud” between Roll and Parker, it said, and the discord had ended before the investigation got underway.

Roll had undergone exploratory surgery July 13 and a lung tumor was found, but was not removed; doctors determined that chemotherapy was preferable to surgery. The district attorney resigned a few hours before his death, at his home.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company