Tuesday, February 5, 2008

Page 11

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

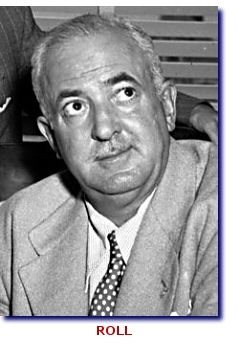

District Attorney S. Ernest Roll Serves as Host of Early TV Talk Show

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifty-Ninth in a Series

S. ERNEST ROLL (his unused first name was “Silas”) on May 8, 1951 assumed the role of Los Angeles County’s thirty-third district attorney…and three months later, became a pioneer television broadcaster.

He automatically took charge of the DA’s Office, on an interim basis, upon the death of the incumbent. The April 30 issue of the Los Angeles Examiner explains:

“Control of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office today will be assumed by S. Ernest Roll, chief deputy to William Simpson, who died Saturday night.

“Roll succeeds to Simpson’s office on a temporary basis under an ordinance establishing a line of succession for all county department heads, holding the position until action by the Board of Supervisors fills the vacancy.”

![]()

I

would assume that DAs before Roll

had appeared on television. Telecasting began here on Dec. 23, 1931,  over

experimental station W6XAO (Channel 1), now known as KCBS (Channel 2), and by

1951 seven channels were in operation. But it was Roll who was the first

district attorney to utilize television as a regular meeting-place with

constituents.

over

experimental station W6XAO (Channel 1), now known as KCBS (Channel 2), and by

1951 seven channels were in operation. But it was Roll who was the first

district attorney to utilize television as a regular meeting-place with

constituents.

An early, if not initial, experience for Roll on television came on May 25, 1951, when he fielded questions from three newspaper reporters—one each from the Times, the Mirror, and the old Daily News. It occurred on the Greater Los Angeles Press Club program, aired at 10:30 p.m. on KECA, then the call letters for Channel 7. He apparently did well enough that he was not rendered TV-camera shy.

The Long Beach Independent’s issue of Tuesday, Aug, 7, 1951, notes:

“D. A. on TV—S. Ernest Roll, district attorney for L. A., assisted by Ed Lyon and Freeman Lusk, presents a l5-minute discussion of problems of his office in a new telecast on KLAC (13) at 8:15 p.m. It will be a regular weekly show hereafter.”

Roll was not the only local politico with a weekly television program in 1951. Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron was on KTLA (Channel 5) on Fridays at 7:15 p.m. And Gov. Earl Warren’s “Report to the People” was aired monthly by KECA on Wednesday nights, at varying times. This was before videotape and the governor came to the KECA studio to be broadcast live. Plans had been made earlier in the year for the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to hold actual half-hour sessions at KECA studios on Wednesday nights at 10:30, starting Feb. 7, but at the last minute, the project was scratched by the lawmakers.

![]()

Roll’s 15-minute show on Channel 13 followed a newscast of the same duration by the urbane Clete Roberts. On opposite the district attorney were movies on KECA and on KFI (Channel 9), and as well as wrestling on KNBH (Channel 4) and Ginny Simms’ “Front and Center” (an “amateur hour” from nearby armed services camps) on KTTV (Channel 11).

So, Roll was the air during prime time, with competition that was hardly compelling. But that was in August.

On Sept. 25, “Texaco Star Theatre” with Milton Berle—known as “Mr. Television”—returned after a summer of hibernation. (His guests included Eddie Cantor.) Roll was lucky if his own wife was viewing his show that night, or in succeeding weeks.

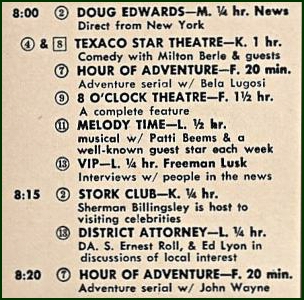

Also, CBS’ nightly news broadcast, with Douglas Edwards, was now opposite Roll. Here’s the 8-8:30 p.m. line-up of shows on Nov. 20, 1951, as contained in “TVTime,” a local magazine with listings of television shows (like “TV Guide,” which was then serving only east coast cities):

|

|

The letter “M” to the right of “Doug Edwards” stands for “microwave,” indicating that the broadcast was live. Coast-to-coast television broadcasting, via microwave relaying, began Sept. 23. Berle’s show, designated by a K,” was a Kinescope—a film of a production originally broadcast live, captured by a camera aimed at the studio monitor. Emanating from New York, the show had been broadcast one week earlier throughout the east, with the “kine” sent here by mail. “F” stands for “film,” and “L” for “live.” Channel “8” is in a square, while others are in circles, to differentiate KFMB, located in San Diego, from Los Angeles stations. It was listed because its signal could often be picked up in those days on TV sets here. |

|

On Jan. 17, 1952, KLAC mercifully shifted Roll’s program to Thursday nights at 8:30. He still had stiff network competition, however; he was now on opposite “Burns and Allen” on Channel 2 (which on Oct. 28 had become KNXT, a station owned and operated by CBS). Later, Roll’s show was shifted to 8 p.m., where the chief rival was NBC’s Groucho Marks on KNBH…and other time slots…and finally to 7 p.m. up against “Range Rider” and the “Ruggles.”

His final broadcast was on Dec. 18, 1952.

Roll’s guests through the months included William Ritzi, his chief deputy handling juvenile cases…later a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court (Nov. 6, 1951); one of his investigators, William Yoakam, with whom he discussed enforcement of narcotics laws (Nov. 20, 1951); Deputy District Attorney Ted Sten of the Long Beach office (April 10, 1952), Los Angeles Bar Assn. President Stevens Fargo, who later became a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court (July 17, 1952); U.S. Attorney Walter Binns (Oct. 16, 1952); Los Angeles County Chief Probation Officer Karl Holton (Nov. 6, 1952); and Walter Gordon, chair of the California Adult Authority, a forerunner of the Board of Parole Hearings.

Roll was not above self-promotion. The Times’ Feb. 14, 1952, television column by Walter Ames contains this item:

“Our District Attorney, Ernest Roll, called to remind me that an old friend, Judge Daniel Beecher, is his guest tonight at 8:15 on KLAC (13). Judge Beecher is singing his swan song to public service after more than 23 years in the prosecutor’s office….”

Beecher had served as an appointed Los Angeles Superior Court judge from Aug. 3, 1927 until his term ended on Jan. 7, 1929. (He was defeated in the 1928 primary election, and failed to make a comeback in a 1932 run-off.)

Roll’s guest on Oct. 2, 1952 was Los Angeles Superior Court Judge William B. McKesson. It could not have been supposed that night that the man Roll was interviewing would be chosen as his successor upon his death in office.

![]()

Roll was on the air in 1952 during the period when he was a candidate to succeed himself. Nonetheless, his opponent did not demand “equal time.” The “equal time” provision of the Federal Communications Act (§315) became somewhat of an issue in the late 1950s, and an incendiary one in the early 1960s, with broadcasters agitating for its repeal…though the mandate was nothing new. It had been in the act since it was passed in 1934, and had its roots in the 1927 Radio Act. It just hadn’t been frequently invoked.

In more recent times, it has been carried to absurd extremes, with movies in which candidates Ronald Reagan or Arnold Schwarzenegger had roles being eliminated by broadcasters from the airwaves during the erstwhile actors’ respective candidacies, in order to avoid equal time problems. An episode of Disney’s “Mouse Factory,” scheduled to run in January 1972, was held back by NBC after the FCC told it that §315 applied; the guest host was comic Pat Paulsen (since deceased), pursuing one of his gag runs for the presidency of the United States. In a 1974 ruling, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said:

“It appears clear that Paulsen’s ‘Mouse Factory’ appearance resulted from his status as an entertainer rather than as a candidate. However, unless a clear rule exists that all broadcast use by a political candidate subjects a station to equal time obligations, broadcasters and ultimately the FCC would be forced to examine the nature of a candidate’s every appearance to determine whether it falls under § 315.”

![]()

The

1952 challenger to Roll

who overlooked his “equal time” right was attorney/minister Claude A. Watson, who staged only a token  campaign.

campaign.

Watson was an interesting character. In 1944 and 1948, he had been the Prohibition Party’s candidate for president of the United States (and was its vice presidential nominee in 1936). During the 1948 election, he sent his wife to the White House to measure it for drapes, in anticipation of them moving in. (His wit appears to have been on a par with Paulsen’s.)

He also ran for state attorney general, on the Prohibition ticket, in 1942, 1946, and 1950.

Watson captured less than a third of the votes in the 1952 race for DA. But for him, 30.5 was a huge percentage. In his 1944 and 1948 presidential contests, he received .4 percent, and in his 1950 run for attorney general secured 2.7 percent.

During the course of the campaign, the newspapers lined up behind the incumbent.

A Feb. 14 editorial in the Van Nuys News observes that while voters had some “perplexing decisions to make,” there was at least one contest “which should give no concern—that of County District Attorney.” It credits Roll with conducting “the office solely in the public interest, without special favors to any person or group of persons, and without the slightest tinge of prejudice.”

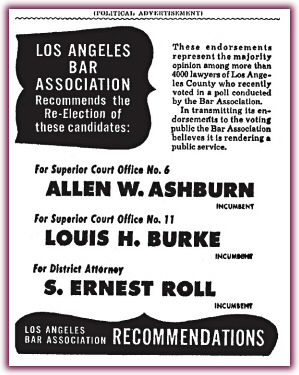

That

year, the Los Angeles Bar Assn., which had long publicized its choices in

judicial races, based on plebiscites conducted among its members, made an

endorsement of Roll. It placed this ad in various newspapers:

Roll fared even better in the 1956 election…in fact, as well as possible. Replicating the feat of his predecessor, Simpson, he ran without opposition.

![]()

He had been born in Long Beach (on Jan. 22, 1904), and had for many years been a resident of that city. But his duties as a deputy district attorney never took him to the Long Beach courthouse to try a case. As district attorney, however, he appeared in that courthouse for the first time.

The Feb. 25, 1953 issue of the Long Beach Press-Telegram tells of Roll turning up in a courtroom in his hometown for the purpose of arguing in favor of the appointment of two psychiatrists to determine if a murder defendant was fit to be tried. He prevailed despite vehement defense objection.

He then did what a fictional Los Angeles district attorney, Hamilton Burger, was to do with frequency on TV’s “Perry Mason” starting in 1956: personally handle a preliminary hearing. The Press-Telegram’s April 15, 1954 report explains that Roll wanted “to familiarize himself with operation of local courts.” The defendant, an alleged thief, was bound over for trial.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company