Thursday, November 1, 2007

Page 11

REMINISCING (Column)

M & M Comes to Defense of Boycotted Brewery

By ROGER M. GRACE

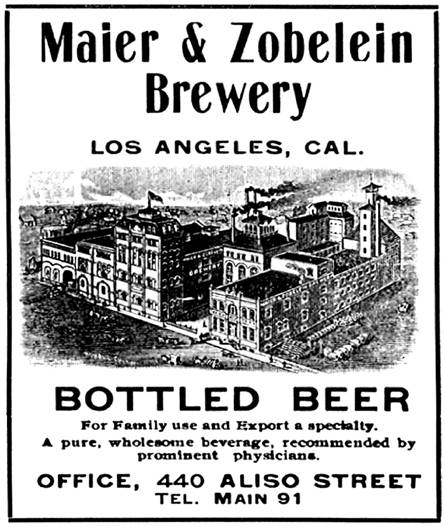

Joseph Maier and George Zobelein were in business together from 1882 until Maier died in 1905. They owned a massive brewery, constructed in 1875, just east of the Los Angeles Civic Center, on Aliso Street. (You know just where it was if you recall the massive lettering on the side of a building off the Santa Ana Freeway reading, “Home of Brew 102”…a brand that came into existence after World War II.)

The plight of Maier and Zobelein in 1897 troubled the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Assn. of Los Angeles. Organized labor was urging that the public boycott their beer. Why? Because they were treating their 65 employees too well.

Workers at the Maier & Zobelein plant were receiving higher wages than those being paid by union shops. Many of them were shareholders in the company. They were happy. They saw no reason to unionize, and a good reason not to: they would have to pay dues.

The San Francisco local of a national brewery workers’ union discerned oppressiveness on the part of management. A union publication, the Coast Seaman’s Journal, provides this insight into the thinking behind the labor action:

“The failure of the employees of any brewery to join the union proves that force is being used by their employers to prevent them from doing so.”

On Oct 18, 1897, the M & M board passed a resolution declaring that the boycott “is unjust and uncalled for, and is against all principles of American institutions, and a serious menace to the freedom of action guaranteed to every citizen under the Constitution of the United States.”

The M & M added that it “deprecates the action of the labor organizations, and pledges hereby its moral support to Maier and Zobelein brewery and its employees in their present struggle.”

That was the first time the M & M took a stance in opposition to actions of organized labor. It would not be the last. In the years ahead, the organization would be one of the nation’s most forceful advocates of the open shop.

Support for Maier and Zobelein came also from the Los Angeles Times—which had been the object of a six-year boycott, triggered by a strike that commenced Aug. 5, 1890. (Further, and more intense, conflicts with unions would unfold in years ahead.)

In an Oct. 12, 1897 editorial, the newspaper rails:

“The position of the labor unions in this matter is utterly indefensible, as their action is infamous. As individuals, and as citizens, the employés of Maier & Zobelein have a right to remain outside of the union if they so elect. To join it would mean a reduction of their wages, as their employers could not be expected, if their establishment were ‘unionized,’ to pay higher wages than the union scale. It is a clear use of attempted bulldozing, as well as of dastardly interference with individual rights.”

The bulldozing eventually worked. In the summer of 1901, Maier & Zobelein entered into a contract with the Pacific Coast Union of Brewery Workers. Under the accord, the workday was cut back from nine hours to eight.

An article in the Times on June 10, 1903, observes:

“Beer is the solitary product that the labor unionists are able to boycott successfully. It is perfectly natural that this should be so. The unionists are the chief patrons of the mug by a most convincing majority. As they consume the largest share of the beer, stoppage of their patronage is fatal to the industry of making it....

“There are no non-union breweries.”

The union had just succeeded in revising the wages and hours of workers in the Maier & Zobelein engine-room, the article notes. A three-day boycott did the trick.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company