Monday, December 31, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

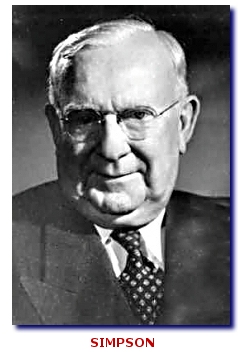

DA William E. Simpson: His Smile Was Benign, His Tongue Could Be Sharp

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifty-Eighth in a Series

WILLIAM E. SIMPSON, appointed

by the Board of Supervisors in 1946 as the 32nd district attorney of Los Angeles County, was uncontroversial. In marked contrast to some of his recent

predecessors, he was solid and trustworthy...inspiring confidence to the extent

that in 1948, he attained the remarkable—perhaps singular—feat of being elected

DA of this county without opposition.

Angeles County, was uncontroversial. In marked contrast to some of his recent

predecessors, he was solid and trustworthy...inspiring confidence to the extent

that in 1948, he attained the remarkable—perhaps singular—feat of being elected

DA of this county without opposition.

(Uncertainty as to whether any other Los Angeles DAs coasted into office with no competition is based on the murkiness surrounding the elections of the county’s early office-holders.)

Simpson declared his candidacy for election as district attorney on Jan. 31, 1948, releasing a list of the 150 prominent citizens who constituted his campaign committee, and no one challenged him.

So it was that heading the county’s prosecutorial office as the first half of the 20th Century came to a close was this roly-poly, white-haired, bespectacled and avuncular figure—who, with padding, would have been an ideal department store Santa. Mellow though his appearance was, he was a hard-nosed, tough-talking prosecutor who, had he still been alive, would probably have applauded the 1972 suggestion of Sen. Ed Davis (since deceased) that hijackers be hanged at the airport.

![]()

The Board of Supervisors chose Simpson, 57, as district attorney on Nov. 26, 1946, to fill out the unexpired term of Fred Howser who had resigned effective Dec. 1. Howser would assume his new duties in January as state attorney general.

Simpson had previously served as a Democratic state assemblyman, representing Kern County from 1913-15. He was a sponsor of legislation to establish absentee balloting, his bill passing both houses but dying for lack of signature by the governor.

He also served two stints as Fresno city attorney, an appointive position. On Nov. 22, 1923, the city council voted to refund $55,000 in taxes based on Simpson’s advice that the city had violated the law in collecting more money than it needed. He tendered his resignation in 1925, in keeping with custom, because of the election in April of a new city administration, but remained for four months, as requested, until a successor was trained.

An Associated Press report of June 30, 1926, says that Simpson, chosen by a “conference of state Democratic leaders” to be the party’s nominee for a congressional seat, declined to run.

![]()

Prior to his appointment as Los Angeles district attorney, Simpson had worked in the DA’s Office for some years…sporadically.

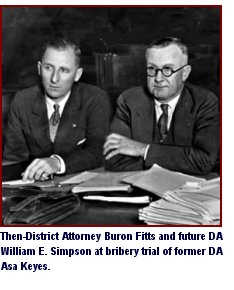

On Dec. 3, 1928, Buron Fitts, after being sworn in as

district attorney, announced the names of those who would serve in key posts in

his administration. Simpson, he said, would be a member of the special trial

squad (prosecuting outgoing DA Asa Keyes for perjury), crediting him as being

“one of the ablest trial lawyers in California.” Simpson’s salary was $600 per

month.

On Dec. 3, 1928, Buron Fitts, after being sworn in as

district attorney, announced the names of those who would serve in key posts in

his administration. Simpson, he said, would be a member of the special trial

squad (prosecuting outgoing DA Asa Keyes for perjury), crediting him as being

“one of the ablest trial lawyers in California.” Simpson’s salary was $600 per

month.

Simpson drew similar praise from Fitts when he resigned as a deputy effective Aug. 1, 1929, to team with his brother in law practice. “The loss of Simpson is one of the greatest ever to face this office,” Fitts remarked.

In 1934, Simpson performed prosecutorial duties as special counsel for the State Bar in presenting evidence to the Los Angeles County Grand Jury that six claims adjusters and two attorneys had pressured accident victims into retaining services of the attorneys. The State Bar was attempting to crack down on ambulance chasing.

Loyal to his old boss, Simpson served as one of his defense lawyers when Fitts was tried for perjury in 1936. Fitts was acquitted, and on Nov. 23 of that year, he named Simpson as his chief deputy to replace the holder of that post who had died.

“Mr. Simpson, with some reluctance, left a lucrative private practice to accept this appointment,” Fitts declared. “He accepted the appointment on the basis of what he considered a public duty.”

The DA went on to say:

“I am so certain that in this appointment I have been able to guarantee Los Angeles county an honest, fair and efficient performance of public duty that I hope Mr. Simpson’s personal affairs may not make it necessary that he return to private practice. If such a situation should develop, the people of this county will have profited greatly by his service here.”

Simpson did find it necessary to return to private practice, doing so on Feb. 1, 1938.

The following year, the Board of Supervisors named him special counsel in a graft investigation. The job would, obviously, have meant money in his pocket. But he looked over the law, saw that no legal authority existed for such an appointment absent a vacancy in the office (and there wasn’t any), and on Aug 24 declined the job offer.

On May 21, 1940, Simpson rejoined the office, which was still headed by Fitts, accepting a position as head of a trial unit. His pay was now $500 per month, $100 less than he was making before he resigned as chief deputy. He served in the office under the brief term of District Attorney John Dockweiler, then under Howser. Simpson had worked his way back up to a monthly salary of $600 by the time Howser awarded him the post of assistant district attorney on June 5, 1944, with his pay now jumping to $700 per month, later rising to $725.

Howser on July 17, 1945, shifted Simpson to the post of “chief deputy district attorney” when its occupant resigned, and abolished the position of “assistant district attorney.” The pay remained the same.

![]()

“The Gambler and the Bug Boy,” a book by John Christgau published this year, tells of the Los Angeles Superior Court trial in 1941 of five men accused of fixing horse races. Simpson was one of the two prosecutors.

Christgau recites that Simpson “had gray hair and dimpled cheeks, and he was never without a small smile that reflected a warm heart.” He adds:

“But his kindly face belied how scorching and aggressive he could be in cross-examining witnesses.”

The author proceeds to recount incisive, rapid-fire cross examination of the main defendant.

The Times’ May 24, 1941 story on closing argument in that case notes:

“When the jurors filed out to commence their deliberations they still had ringing in their ears the voice of Prosecutor Simpson, who excoriated the defendants for ‘corrupting these boys (jockeys) and making them prostitutes in their own profession.”

He may have looked like a pussycat...but he roared.

![]()

And roar he did in connection with a scandal in 1949.

Atop the lead story in the Aug 16, 1949 edition of the Los Angeles Times is this headline:

The story reports that transcripts of conversations which took place in the West Los Angeles home of mobster Mickey Cohen, and were electronically recorded by police, had been turned over to Mayor Fletcher Bowron and Police Chief William A. Worton.

“Copies of the transcript, covering a period from April 13, 1947, to March 17, 1948, are in possession of the Times and the San Francisco Chronicle,” the article says. “They have not been disclosed until now in cooperation with law enforcement authorities.

“Existence of the transcripts has been known to the Times for several months.”

While their existence was long known to the Times, it was apparently not known for any appreciable length of time to the police chief—who had assumed office on June 20 of 1949 (after his predecessor, facing a perjury investigation, resigned)—nor to Bowron nor Simpson.

An Associated Press dispatch from Los Angeles on Aug. 16 begins:

“District Attorney William A. Simpson today angrily demanded a full investigation of ‘the foul-smelling two-year-old mass of corruption and concealment’ as disclosed by records of conversations in the home of gambler Mickey Cohen.

“‘When the grand jury reconvenes next month I’m going to demand that it institute searching inquiry to learn why this matter has been ‘aged in the wood’ more than two years through two grand juries and not placed in the hands of the agency (district attorney’s office) required to prosecute criminal conspiracy when found,’ said Simpson in a statement.”

The report goes on to say:

“Simpson said he is asking Police Chief William A. Worton for a complete story of the original transcript which reportedly is a record of Cohen’s calls to Cleveland, New York city, Miami, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and Fresno in connection with underworld activities.

“Worton said he learned just a week ago that the transcript of many conversations between Cohen and his henchmen two years ago, made possible by underground wires to Cohen’s home, were in existence.”

Simpson was upset that the surreptitious recordings had been made…but given that they were made, he was all the more riled that the information that was obtained had been kept secret from him. He declared on Aug. 19:

“It is my opinion that all law enforcement agencies have, as a result of this matter, been placed under a cloud of suspicion and I intend, if possible, to fix responsibility and restore public confidence in honest law enforcement agencies.

“I propose to find out why the information obtained was withheld from the chief prosecuting agency of this county, and the District Attorney’s office placed in the category of Little Orphan Annie.”

Still roaring on Aug. 26, the district attorney told about 60 police chiefs from cities throughout the county, assembled in his office:

“I know that there are gambling, slot machines and bookmaking in many towns around the county. I want it stopped.

“You had better look around and clean up your own backyards. If you can’t handle the situation, my office will. We are available to clean up any situation that local police either cannot or will not clean up.”

![]()

Appearing on Dec 8, 1949, before the Assembly Committee to Investigate Sex Crimes, Simpson said of sex offenders:

“I don’t take the view of the psychiatrists that they’re sick people. I feel they’re mad dogs—and should be disposed of the same way.”

This reaction appears in a Dec. 10 column in the Long Beach Independent:

“[Simpson] was the only one at the conference that seemed to have a dynamic approach to the subject.

“ONE MAY not like his language, but if we had more law enforcement officials who talked that way we would have fewer child molesters.”

![]()

Rumors were rampant in 1951 that Simpson, in ill health, was about to resign. On March 22, he wrote a letter to the Board of Supervisors in which he declared:

“I do not intend to resign or retire….On the contrary, I intend in 1952 to stand as a candidate for re-election and to submit my record for the approval of the people.”

Simpson’s fighting spirit was not enough to overcome his illness. He died on April 28.

The obituary in the Los Angeles Examiner the next morning mentions that the attending physician was Dr. Marcus Crahan. He had also been attending physician to District Attorney John Dockweiler when he died eight years earlier. Dockweiler was his brother-in-law.

![]()

None of the eight men who served as Los Angeles district attorney in the first half of the 20th Century was cast from the same mold as any of the others.

James Rives (1899-1903) was dedicated to the law, and unwilling to be corrupted by politics. John D. Fredericks (1903-15) was corrupted by politics, taking orders from bosses. Thomas Lee Woolwine (1915-23) was incorruptible, but volatile (taking a poke at opposing counsel in court, while serving as DA) and unpredictable. Keyes (1923-28) came to associate with members of the “underworld,” in the end becoming a crook, himself, winding up at San Quentin for taking a bribe to throw a case.

Fitts (1928-40) was a cry-baby, prone to wail about attacks on him; he was indicted for perjury, but acquitted. Dockweiler (1940-43) wanted to be a top-notch DA, but health problems limited his energy, and he died in office after pushing himself too hard. Howser (1943-46) was never indicted but widespread suspicions were evoked that he had been corrupt as DA, then as state attorney general.

And then came Simpson, possibly the best of the lot…though behind Rives and Woolwine in intellect.

Next year, I’ll look at the Los Angeles County district attorneys who served in the latter portion of the 20th Century.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company