Monday, December 24, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Howser Becomes DA, Then AG...but Apparent Gambling Ties End Career

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifty-Sixth in a Series

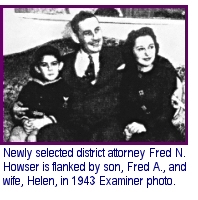

FRED N. HOWSER was appointed as the 31st district attorney of Los Angeles County after the Board of Supervisors settled on him during a closed-doors “emergency” session on Feb. 1, 1943. The following day, in a public session, the board unanimously confirmed its choice of Howser, a 38-year-old Republican assemblyman, to succeed John F. Dockweiler, who died three days earlier.

Howser did not excel as a district attorney. Many would say he was corrupt...and would say that with good reason, though he was never officially charged with any crimes.

The heftiest of the accusations came after he had left the post of district attorney, and the most damning appeared in 1974 in diaries of columnist Drew Pearson, published posthumously.

![]()

John Anson Ford was one of the supervisors who voted in the public session to appoint Howser. Just before the vote was taken, Ford disclosed that he had not voted for Howser at the previous day’s executive session, but was going to do so now. The Times’ edition of Feb. 3, 1943, reports:

“Ford

said that he had heard charges that Howser represents gambling interests, but

after a frank talk with the new District Attorney found nothing to indicate he

was a part of an underworld plot. Ford said he nominated and originally voted

for Daniel Beecher.”

“Ford

said that he had heard charges that Howser represents gambling interests, but

after a frank talk with the new District Attorney found nothing to indicate he

was a part of an underworld plot. Ford said he nominated and originally voted

for Daniel Beecher.”

(Beecher had been chief trial deputy under both Dockweiler and his predecessor, Buron Fitts, and was a former Los Angeles Superior Court judge.)

In his 1961 book, “Thirty Explosive Years in Los Angeles County,” Ford recounts having participated in the appointment of four district attorneys. He notes that in one instance, he “declined to go along with the selection of the majority until I had an opportunity to talk frankly with the person selected about his short comings as I saw them.”

Clearly referring to Howser, the account continues:

“Following this conference I joined the board and made its selection unanimous—a vote that was to be one of a very small number that I deeply regretted. My heart-to-heart talk proved fruitless.”

The vote was followed by the swearing in of Howser and the utterance of remarks by him “[w]ith tears in his eyes,” according to the report in the Herald-Express.

![]()

The appointment of Howser was unexpected. The Los Angeles Examiner, in its Feb. 4 edition, quotes Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron as saying:

“The day after John Dockweiler died, the five members of the Board of Supervisors met in secret, in a room, and selected his successor.

“Their decision was a surprise to me and to a great majority of the people of the county.

“Most of us felt that the choice would be among the three competent assistants of the late District Attorney, Clyde Shoemaker, Grant Cooper and Daniel Beecher.”

Bowron decried the haste in making the appointment, without opportunity for public input.

A Long Beach Independent editorial of Feb. 5 reflects public reaction to the selection of Howser, who represented that area in the Assembly (and had served as Long Beach’s assistant city prosecutor for six years):

“The appointment has caused a tense situation wherein it has been charged, and is talked about on every street corner, that this appointment was forced by interests desiring to ‘open up the county.’ The fact that majority members of the five supervisors, only a week previously voted in favor of pinball machines, gave credence to this gossip and rumor.”

A Feb. 7, 1943, editorial in the Oakland Tribune says:

“The quick appointment of Assemblyman Fred N. Howser...was...not without its element of surprise, in fact it astounded many of those who thought they were close to the political picture in Los Angeles County.”

(Selection of a DA in private session remained lawful even after the 1953 enactment of the Brown Act, personnel decisions being exempted from the open-meetings requirement. Since then, two DAs were selected in closed meetings—Joseph Busch in 1970 and John Van de Kamp in 1975; two were selected publicly…William B. McKesson, in 1956, and Robert H. Philibosian in 1982.)

![]()

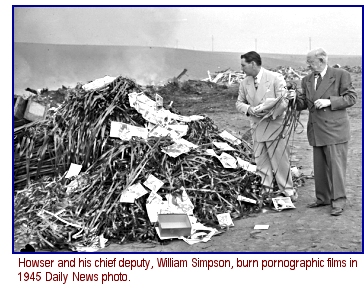

Relations between Howser and Bowron proved stormy.

On July 29, 1943, Howser released to the press his missive to the police chief, as well as the president of the Police Commission, raising the prospect of the DA’s Office undertaking to make arrests in the city.

The letter—which implies that graft was rampant under the administration of Bowron (who had gained office in a recall election as a reformer)—says:

“Constant reports of wide-spread gambling and prostitution within the city limits of Los Angeles, coupled with complaints of wholesale fleecing of military personnel and warworkers, have led to an investigation by this office.

“Within the past few days my investigators have uncovered and arrested enough gamblers and racketeers to convince me that serious conditions prevail.

“Alarming as the general vice situation is, two factors brought to light in the preliminary investigation are even more disturbing to me. The first of these is the fact that some of these establishments apparently have operated unmolested for long periods of time. The other is the growing belief that this seeming impunity results from official protection.

“This office stands ready to see that organized vice is not permitted to flourish within the city or county of Los Angeles. In the event the city Police Department is either inadequate or too embroiled to act decisively I will, of course, divert enough of my staff to ensure Los Angeles a clean, decent government, in fact as well as in name.”

Bowron’s statement in response reads, in part:

“Your effort, by insinuation and innuendo, to create the belief in the mind of the public that gambling and prostitution exists in Los Angeles as a result of immunity and official protection is not only untrue but is cowardly and demonstrates your incapacity and disqualification to act as the chief law enforcement officer of the county.”

![]()

The

next year, Howser ran to

succeed himself. One of Dockweiler’s brothers, Henry I. Dockweiler, competed

with Howser, as did a former Sonoma assistant district attorney, Wallace L.

Ware (who was to be appointed to the Los Angeles Superior Court in 1953).

Los Angeles Superior Court in 1953).

Kyle Palmer, political editor of the Los Angeles Times, was none too gentle in sizing up Howser. An opinion piece appearing in the newspaper on April 30 says:

“Despite his possession of the office, Howser is really the masked marvel in this supremely important local contest; for he got the appointment in secret and has remained somewhat of a mystery during the months of his incumbency.

“Neither by training, experience or maturity does he measure up to the calibre of the chief subordinates in his office.”

Palmer notes that Howser had heftier financial backing than his two rivals combined, but credits Dockweiler and Ware with “integrity” and “character,” as well as competence—though noting Dockweiler’s relatively weak background in criminal law and in administration.

Money and incumbency were sufficient factors to give Howser the victory in the May 16 primary—though the closeness of the vote in the early returns caused the Herald-Express to announce atop the page of its May 17 issue: HOWSER TO FACE RUNOFF.”

The results were 346,501 votes for Howser, 175,501 for Ware, and 166,174 for Dockweiler.

Howser’s political career was on the upswing. He had lost congressional races in 1932, 1934, and 1936; won Assembly seats in 1940 and 1942; and would be elected attorney general in 1946. He went downhill after that.

![]()

The tale of how Howser came to be elected attorney general is told by former state librarian Kevin Starr, a noted writer on California history, in his 2002 book, “Embattled Dreams: California in War and Peace, 1940-1950,” as follows:

“In 1946 Artie Samish, a powerful Sacramento lobbyist representing liquor and racetrack interests, was in search of an easy-going candidate to replace [Robert] Kenny as attorney general, since Kenny had reluctantly entered the governor’s race. Samish backed Frederick Napoleon Howser, the lackadaisical district attorney of Los Angeles County. A strong recommendation for Howser, cynically pointed out to his confrères, was that Howser’s name closely resembled that of the popular incumbent lieutenant governor, Fred Houser, and Samish correctly guessed that most voters would vote for Howser thinking they were voting for Houser.”

The Times’ April 30 column bearing the byline of “The Watchman” contains this:

“Assemblyman Harrison Call, two-fisted colorful candidate for Attorney General, swung into town yesterday and made this sage observation:

“ ‘I’m not fighting a candidate—I’m fighting an illusion!’

“What Call meant, he said, was that wherever he found people favorable to the candidacy of Fred Howser, the local D.A., he found that the people thought he was Fred Houser, the Lieutenant Governor.”

The name of Houser rang a bell all the more because the lieutenant governor’s father, Fred W. Houser, was a justice of the California Supreme Court up until his death in 1944.

(Howser’s victory marked one of many examples of voter confusion based on similarity of names. The prime example would seem to be the election in Texas in 1976 of one “Don Yarbrough” as a member of the state’s Supreme Court. He spent only $350 in connection with his campaign and made one speech. He was elected, plainly and simply, because voters confused him with one of the state’s U.S. senators, Ralph Yarborough, who had one more syllable in his surname and a great deal more credibility. Yarbrough, faced with indictments for perjury and forgery, resigned after seven months, fled to Grenada, and was eventually apprehended, brought back to Texas, and imprisoned.)

Starr notes that although Republican Gov. Earl Warren (later chief justice of the United States) “loathed Howser as a tool of Samish, he could not bring himself to endorse [Democrat Edmund G. “Pat”] Brown openly.” He continues:

“Howser, a Republican, was elected, and Samish got his wish; not only was Howser willing to look the other way as far as Samish’s clients were concerned, the attorney general’s own coordinator for law enforcement was secretly running a string of slot machines in Mendocino County.”

![]()

Howser was an embarrassment to the governor given that the attorney general was a member of the same political party.

Warren acted to put Howser’s activities in check by appointing the Special Crime Study Commission on Organized Crime in 1947, headed by attorney Warren Olney III (son of a California Supreme Court justice, grandson of an attorney who was a founder of the Sierra Club, and father of Warren Olney IV, a respected local broadcast journalist).

William

Somers Mailliard was secretary to Warren in 1948-51 (later becoming a member of

the House of Representatives and an ambassador). Interviewed October 5, 1971,

as part of the Earl Warren Oral History Project conducted at the University of

California at Berkeley, he said:

William

Somers Mailliard was secretary to Warren in 1948-51 (later becoming a member of

the House of Representatives and an ambassador). Interviewed October 5, 1971,

as part of the Earl Warren Oral History Project conducted at the University of

California at Berkeley, he said:

“[W]e knew, of course, that Howser was a crook, and Earl, particularly, knew because of those gambling ships in Los Angeles when Howser was district attorney. One of the main reasons for the creation of the Commission on Organized Crime was to watch Howser.”

Mailliard noted that “it was common knowledge that Howser was going to organize the slot machine rackets with a payoff in every county in the state,” and went on to say:

“[A]s I understood it, there was some concern about evidence that organized crime was moving into California, and that it was corrupting the lobbyists, and the whole ball of wax began to look a little unsavory. But one of the duties of the crime commission was to keep Howser under surveillance, with the result that he never was able to put it together. It was commonly understood; Howser even told friends that he only wanted to be attorney general for four years and that he’d retire with a couple of million dollars.”

![]()

A fact-finding committee of the powerful California Republican Assembly recommended that Los Angeles attorney Ed Shattuck be the party’s 1950 nominee for attorney general, not Howser.

“A History of The California Republican Assembly” by Louise Leigh and Fred Davis, published by the CRA, recounts:

“At the 17th Annual CRA Convention at San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel on March 25, 1950, incumbent Attorney General Howser urged party unity and asked CRA to make no endorsement for attorney general. The San Francisco Chronicle characterized his plea as ‘almost tearful.’

“The Chronicle story disclosed testimony before a Sonoma County Grand Jury that ‘the punchboard monopoly put $50,000 into Howser’s 1946 campaign as the purchase price for immunity from interference’ by the attorney general’s office. Before CRA, Howser reportedly called such charges ‘scurrilous and scandalous lies.’

“The CRA delegates unanimously endorsed Shattuck for Howser’s job, and accused Howser of having allowed ‘vicious growth and development of organized crime and rackets.’ ”

Shattuck defeated Howser in the primary, but lost to Pat Brown, a future governor, in the general election.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company