Tuesday, December 18, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

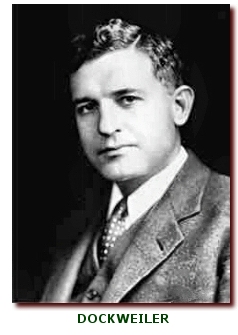

DA Dockweiler Terms Los Angeles Bar Association ‘Gutless, Spineless’

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifty-Fourth in a Series

JOHN F. DOCKWEILER, sworn in as Los Angeles County district attorney on Dec. 2, 1940, lost no time in plunging into controversy. In an address on Dec. 11 before the University of Southern California’s Law Alumni Association, he declared:

“Someday I hope to tell the Bar Association to its face that it is gutless and spineless when it comes to protesting the conduct of certain prosecutors and lawyers.”

At least that’s how the Times quoted the remark; the Herald-Express related it somewhat differently, but to the same effect. The following information on the interplay between Dockweiler and the county’s largest voluntary bar association is pieced together from accounts in those two newspapers, as well as the Examiner and the Daily Journal, a legal trade paper.

Getting back to the meeting, held at the University Club... Will H. Anderson (who had been personal attorney for a past DA, Thomas Lee Woolwine), had a question. When Dockweiler referred to the “bar association,” did he mean the State Bar or the Los Angeles Bar Assn.? Dockweiler responded: “Both of them.”

The speaker also told fellow alumni that while he didn’t envision his office becoming a “super police force,” his investigators would make arrests if need be, declaring:

“If the sheriff and various police departments repeatedly refuse to make arrests or discover offenses complained of, I’ll have to make the arrests.”

Pointing to the financial inability of 80 percent of the accuseds in criminal cases to provide for their own defense, the new DA said:

“I hope to save money from my budget and turn the money over to the public defender’s office, because that office should have better lawyers than the District Attorney’s office.”

![]()

Dockweiler had said he wanted to rebuke the bar to “its face,”

and Herbert Freston, president of the Los Angeles Bar Association,

quickly responded by inviting the DA to come before the Board of Trustees at

noon on Dec. 18 to speak his piece.

Dec. 18 to speak his piece.

“You will be afforded a full opportunity to tell the board of trustees just what you have in mind,” Freston said in a Dec. 13 letter, adding:

“We can assure you that you will be given gracious and courteous attention.”

Freston added this diplomatically phrased zinger:

“It has been my privilege to have been officially and actively associated with the Los Angeles Bar Association, either as a member of the board of trustees or as an officer, for the period of at least five years last past.

“During that entire period, while you have been a valued member of our association, you have not, so far as I can now recall, ever attended a single meeting of our association.

“Mention of this is not made in a critical manner, but for the purpose only of emphasizing the fact that for a long period of time you have been entirely out of touch with those things which your association has done and is doing in an effort to keep abreast of the times and to discharge its duty to the community and, particularly, to those members thereof not financially able to obtain necessary legal assistance.”

Dockweiler agreed to appear before the board, but declined the immediate invitation, already being slated to speak at that time before the Lawyers’ Club.

![]()

At the Jan. 15 meeting of the board, Dockweiler was the speaker.

He did not tell the trustees to their faces that they were “gutless and spineless.” Instead, he complained of the proliferation of administrative bodies, comprised of nonlawyers, engaging in adjudications.

“During the last two decades I have witnessed the law practice being whittled away from us,” he said. “Much of this is due to the setting up of administrative bodies to solve the social problems of the people of the nation.”

Nonlawyers staff these bodies and nonlawyers practice before them, with no right of appeal to the courts, Dockweiler protested, adding:

“[T]ake the Wallace-Logan bill which provided that decisions of administrative bodies might be appealed. The President vetoed it with a stinging rebuke, excoriating the profession—excoriating the Bar Association.”

Dockweiler continued:

“The President’s veto indicates that the public does not trust the courts to handle social equations.

“If this thing continues and the bar members and bench fall into innocuous lassitude it will find administrative bodies taking from us these things, letting laymen take over the work intended for lawyers.”

He urged the 14 lawyers attending the board’s lunch meeting to become more aggressive in protecting the bar’s interests, such as effecting a clamp down on the unlawful practice of law by banks and others.

The district attorney observed:

“Attorneys are not fighting to keep their business.

“They are not fighting to keep themselves together.

“They are not striving to endear themselves to the public.”

He had a suggested a means by which lawyers could attain that endearment:

“[I]t wouldn’t be a bad thing to present our picture to the public through a public relations counsel.”

Dockweiler proposed that the bar association adopt a “slogan such as ‘The Lawyer Is Your Best Friend.’”

![]()

Speeches, unlike movies and plays, usually don’t attract reviews, but this one did, and the Times panned it.

A Jan. 16, 1941, editorial says:

“In substance, Mr. Dockweiler’s idea is that the legal profession should forget its long-standing ethical scruples to the contrary, hire a good press agent—euphemistically called ‘public relations counsel’—and advertise, adopt a ‘friend of the people’ publicity slogan and otherwise energetically go after the fees and emoluments which are now slipping from bona fide lawyers into the hands of bankers, corporations and others who render legal services outside the pale of the bar....

“It may be that the law business should advertise. But if so, it should be in a position to guaranty its wares, both as to quality and price.”

Also drawing a dissent from the Times was Dockweiler’s stance, taken on Jan. 9, 1941, that bookmaking should be legalized and licensed to get professional gangsters out of the business and raise revenue for the state.

A Jan. 11 editorial scoffs:

“What would be the result? We would have a bookmaking establishment operating in every residence block and hordes of bet-solicitors, runners, touts and other race-track scum surrounding every school and college building in the county.”

The editorial goes on to say:

“So far as the practical effects are concerned, to license it would not greatly differ from licensing burglary or any other present form of lawbreaking.”

![]()

While Dockweiler’s comments about the bar being “spineless and gutless” created a stir, testimony he rendered on Feb. 19, 1942 precipitated what a Times’ story a few days later describes as “a furore...in the grand-jury room.”

The Times and the competing morning newspaper, the Examiner, both carried summaries of the supposedly secret testimony in their Feb. 20 editions, based on leaks. The Examiner comes right out and says that information came from members of the panel. The basic information is the same, but the slant the rival newspaper took in the telling was markedly disparate.

The Times’ rendition bears a headline reading, “Aide Attached by Dockweiler.” A secondary headline (or “deck”) says: “Prosecutor, Appearing at [Wire-]Tapping Inquiry, Says Deputy Hired Ex-Convict.” The gist of the story is that Dockweiler came before the grand jury, at his own request, to tattle on his chief deputy, Grant Cooper. The lead paragraph declares:

“Dist. Atty. Dockweiler, in a surprise appearance before the county grand jury in its wire-tap inquiry, yesterday accused his chief deputy, Grant Cooper, of placing an ex-convict on the county’s pay roll as an undercover operator against his specific instructions.”

The Examiner’s headline, by contrast, is: “Dockweiler Testifies to Aid Deputy.” The article portrays Dockweiler as having come out of loyalty to Cooper, to rescue him. It begins:

“For the sake of his chief deputy, Grant B. Cooper, who is under serious attack by the county grand jury, District Attorney John F. Dockweiler did some difficult testifying yesterday.”

The Times’ story zeroes in on Dockweiler’s testimony that Cooper diverted $800 from county coffers to the pocket of an ex-convict in defiance of a specific order not to buy the man’s cooperation.

The ex-convict was bookmaker John Osborne, who had earlier told grand jurors that he had received $100 payments weekly from Clifford Clinton (a radio broadcaster and political insider) for eight weeks, then received $50-a-week stipends directly from the District Attorney’s Office.

Osborne was cooperating in an investigation of Charles Rittenhouse, the head of the sheriff’s vice squad to whom Osborne was paying protection money.

According to the Times, Dockweiler testified that he had been tipped off by Assistant District Attorney Clyde Shoemaker that Osborne might be receiving moneys derived from the DA’s “secret service fund.” In going over the books relating to that fund, he found disbursements to one “Clifford Hughes.” That was a fictitious name, Dockweiler learned in questioning Cooper; the payments were actually going to Clinton (proprietor of the Clifton cafeterias), then passed on to Osborne.

“The District Attorney then explained how he became irate at the then existing situation calling attention to his former refusal to pay Osborne anything for his testimony,” the Times’ Feb. 20 article says.

“A heated conference ensued, he said, with Cooper explaining that Osborne was necessary as a key State’s witness for the prosecution of Rittenhouse. Dockweiler said that he then agreed to continue ‘feeding’ Osborne but insisted that the amount be cut from $100 to $50 a week. Osborne is still being paid $50 and under his own name—and not as ‘Clifford Hughes’.”

![]()

The Examiner focuses on Dockweiler backing up Cooper by testifying, though with hesitancy, that he authorized the $50 payments going directly to Osborne. It quotes Dockweiler as telling the grand jurors:

“I knew nothing about the ‘Clifford Hughes’ transaction until I examined the secret service accounts in July, and I’m sure I did not give my consent to that.”

The newspaper says:

“Members of the grand jury stated that Dockweiler’s testimony yesterday had surprised them greatly because, they said, in his conversation with certain of their number Tuesday night, the District Attorney had denied that he had ever given his consent to Cooper to pay Osborne.

“Jury members said they understood that just before Dockweiler was to appear before the jury yesterday Cooper went to his office and pleaded with him to remember that he had given consent and that Dockweiler did the gentlemanly thing by giving his chief deputy the benefit of any doubt.”

Cooper and Clinton were indicted on Feb. 26 on five counts of falsifying the secret service fund records and one count of wire tapping in connection with a surreptitious Dictaphone recording made at Clinton’s house of a telephone conversation between an informer and a police captain suspected of being on the take. Cooper, Los Angeles Police Chief Clemence B. Horrall and LAPD forensic chemist Ray Pinker (later portrayed in some episodes of the original “Dragnet” television show) were charged with six counts of wiretapping in connection with the same case.

Others were also indicted for wire-tapping, and Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron faced an ouster proceeding based on alleged complicity in electronic eavesdropping in City Hall.

The Herald Express’ Feb. 27 edition reports:

“Asked if he planned to suspend Cooper in view of the indictments, Dockweiler replied:

“ ‘Certainly not!’ ”

Cooper had run Dockweiler’s campaign for district attorney.

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOOTNOTE: A visiting Superior Court judge from Sierra County on April 8, 1942. quashed the indictments, holding that no illegal wire-tapping occurs where one party to a conversation has consented to it being overheard or recorded.

This was different from the ground urged by Cooper: that there was no wire connection to telephone circuits—rather there was pick-up of conversations through use of an induction coil—hence there was no wire-tapping.

With respect to the allegation of Cooper and Clinton falsifying records, Judge Raymond McIntosh said:

“The court finds that the person designated as Clifford Hughes was not a nonexistent and fictitious person, but was in fact a living being [Clinton aide Harry L. Ferguson] who assumed the name of Clifford Hughes to aid and assist Grant B. Cooper and Clifford E. Clinton in protecting the identity of a witness in a criminal case not yet finally adjudicated.”

The misconduct charge against Bowron had been quashed by McIntosh a week earlier.

Cooper went on to become Los Angeles County Bar Assn. president in 1960 and American College of Trial Lawyers president in 1962-63. He was chief trial lawyer for Sirhan Sirhan, slayer of U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company