Tuesday, December 11, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

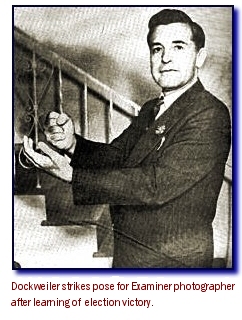

Challenger John F. Dockweiler, Though in Ill-Health, Topples DA at Polls

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifty-Third in a Series

JOHN F. DOCKWEILER, a member of a pioneering Los Angeles family (going back to the Gold Rush days), is the man who defeated Los Angeles District Attorney Buron Fitts in his bid for a fourth term. That happened on Nov. 5, 1940. Dockweiler was sworn in on Dec 2 of that year as the 30th DA for the county.

His tenure was lively, but it was brief; he died of pneumonia on Jan. 31, 1943.

The district attorney was the son of a long-time local lawyer, Isidore Dockweiler, who was to live until 1947. In 1902, the father was the Democratic Party’s nominee for lieutenant governor, losing the race by a slim margin. It was he who was the recipient of a blow to the head administered by attorney Thomas Lee Woolwine on Dec. 31, 1908 during a court proceeding, the aggressor having discerned an insult to his honor. The next year, Woolwine became district attorney.

Among John Dockweiler’s 10 siblings was George A. Dockweiler, who was appointed to the Los Angeles Municipal Court in 1933 and elected to the Superior Court in 1936, serving until his death in 1968. Three of the chief prosecutor’s brothers—Henry, Frederick, and Thomas—were attorneys here. One of those brothers, Henry Isidore Dockweiler, in 1944 made an unsuccessful effort to gain election as district attorney. One sister married an attorney, William K. Young.

A nephew of the new DA was Brian Dockweiler Crahan, a child of 8 when John Dockweiler died. Carrying on the tradition of his grandfather and five of his uncles, Brian Crahan became a lawyer (as did his two brothers); he was appointed to the Los Angeles Municipal Court in 1973, serving in 1982 as presiding judge. He died in 1989.

![]()

John Dockweiler—a graduate of USC’s School of Law, who also engaged in post-graduate studies at Harvard—was elected to Congress in 1932, 1934, and 1936. Ambitiously, he sought in 1938 to wrest the Democratic nomination for governor from Culbert Olson, the incumbent, joining a field of seven challengers. His bid failed.

Dockweiler then undertook to run in the

general election for his Congressional seat as an “independent,” but the Secretary of State’s Office torpedoed that plan, pointing out that state law

precluded it. In desperation, he campaigned for election as a write-in

candidate for Congress, and, predictably, was unsuccessful (though he did pull

2,651 votes, to 9,912 for Leland Ford, nominee of both the Democratic and Republican

parties).

Secretary of State’s Office torpedoed that plan, pointing out that state law

precluded it. In desperation, he campaigned for election as a write-in

candidate for Congress, and, predictably, was unsuccessful (though he did pull

2,651 votes, to 9,912 for Leland Ford, nominee of both the Democratic and Republican

parties).

Then came the 1940 DA’s race. Fitts had prevailed in the 1936 election notwithstanding that he had been indicted two years earlier for perjury. The indictment was based on allegedly lying to the grand jury about a matter. Though acquitted of perjury, the matter about which the grand jury had questioned him raised serious concerns as to his ethics. He had dismissed a morals charge against a defendant right after having engaged in a personal land transaction with that defendant…receiving, by far, the better of the deal (seemingly a gift). Many saw Fitts as no better than his predecessor, Asa Keyes, who wound up in prison.

Voters were, perhaps, resigned in 1936 to a policy of graft-as-usual, no matter who was elected as DA. Prohibition had ended, but the gangsterism it had spawned hadn’t. In 1940, however, a new spirit prevailed. At the City of Los Angeles level, Mayor Frank Shaw, who had turned City Hall into a nest of corruption, was recalled by voters on Sept. 16, 1938, and replaced with Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Fletcher Bowron.

Bowron was, plainly, a foe of Fitts. He had been the judge in charge of the grand jury when Fitts was indicted…reportedly urging that action.

It cannot be doubted that Dockweiler benefited appreciably from Bowron’s call for his election. In the Aug. 27 primary, there were eight candidates; the incumbent came in first and Dockweiler was next. The two would meet in November.

![]()

While Dockweiler had the advantage of support from the city’s anti-corruption mayor (as well as the local Democratic Central Committee and labor groups), Fitts was the beneficiary of backing by the powerful Los Angeles Times, his steadfast ally through the years.

The other major newspapers of that day, the Examiner and the Herald-Express, both Hearst-owned, were not factors in the race. Both newspapers provided balanced news coverage…in contrast to the Times which campaigned for Fitts not only on its editorial page, but in the news columns. The Herald-Express (known at that point as the “Evening Herald and Express”) did not take an editorial stance on the contest. The Examiner did…sort of. What was in essence an editorial is found on a page headed “LOCAL POLITICAL NEWS” in the Nov. 2 issue. An article, in a box, bearing the headline, “Buron Fitts’ Record,’ sets forth the incumbent’s accomplishments and concludes that “Los Angeles County can best serve the public interest by returning Buron Fitts to office by an emphatic majority.”

The Times’ major offensive was that of raising a question as to the state of Dockweiler’s health. In the Oct. 1 edition, an article bears the headline, “Dockweiler Opens Campaign With Mystery Broadcast.” The mystery was whether the candidate’s campaign radio address emanated from the KNX studio or his home.

A news story on Oct. 3 quotes Dockweiler as disclosing that he had experienced a relapse of rheumatic fever, which had first hit him when he was 16, and that he got some rest, as dictated by his doctor (his brother-in-law, Marcus Crahan, father of Judge-to-be Brian Crahan.) The article says the candidate insisted he was now in “fine fettle.”

An editorial that same day, while cautioning against any “whispering campaign” concerning Dockweiler’s condition, asserts “that legitimate inquiry into the facts is justified by public policy” and comments that “[i]t would be an offense against public interest and a breach of good faith either to seek election or permit others to urge election of an individual not physically able to hold office.”

An article on Oct. 22 tells of the endorsement of Fitts by one of his opponents in the primary, Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Irvin Taplin, who came in fourth. The jurist is quoted as saying that he talked with Dockweiler “on more than one occasion” subsequent to the primary—at the candidate’s bedside—and that judging “from his impaired health, I should say it would be impossible for him, if elected, to give the office of District Attorney the kind of direction and leadership to which the voters of Los Angeles are entitled.”

Dockweiler responded by alleging that Taplin had earlier offered an endorsement to him...but with a $20,000 price tag, though in the course of subsequent meetings, the figure was progressively pared.

A Times editorial of Oct 25 calls upon Dockweiler to submit to an examination by three politically independent physicians. That did not occur.

A Nov. 3 front-page article in the Times observes:

“Dockweiler, whose activities in the primary election campaign proved too great a tax on his health, has made an occasional appearance in the runoff contest and has delivered a few radio addresses—some of which were made by remote control from his home. Dockweiler has no experience in criminal prosecutions.”

Below-the-belt though the approach appeared to be, it turned out that the issue raised as to Dockweiler’s health was a legitimate one. The rheumatic fever Dockweiler had contracted as a youth had immediately led to a heart problem which, through the rest of his life, limited his ability to expend energy. As DA, he was to overtax himself in investigating allegations of police brutality, leading to the onset of pneumonia which caused his death.

![]()

In the later days of the campaign, radio commentator (and some saw it, would-be political boss) Clifford Clinton, proprietor of the Clifton cafeterias, teamed with Frank Shaw’s brother, Joe—the bagman during the Shaw Administration, then under sentence to prison—in seeking to promote support for Dockweiler. No repudiation came from the candidate…though denunciation of their efforts did come from Bowron.

Dockweiler’s failure to distance himself from Joe Shaw—who had been convicted on 63 felony counts of altering public records in connection with the selling of Civil Service jobs—is difficult to grasp. Can you imagine Watergate figure John Ehrlichman aligning himself, from prison, with Gerald Ford in his 1976 presidential campaign with nary a word of disclaimer from the Ford camp?

In retrospect, Clinton’s role was near-comical. In a radio broadcast on Oct. 21, on which Joe Shaw was a guest, Clinton announced the existence of a sworn statement by one Peter Del Gado alleging scandalous conduct on the part of Fitts. However, a sworn statement by the former police lieutenant was not particularly meaningful; Del Gado was under indictment for perjury. He allegedly lied to the grand jury in favor of Shaw when it was investigating the Civil Service scandal, and was now a fugitive, having fled to Mexico. His statement, obtained in Mexico by Clinton and Shaw, alleged that Fitts, through his chief deputy, had facilitated his flight, in order to avoid his court testimony in favor of Shaw. The deputy purportedly helped him raise $15,000, used by him to pay off the bondsman who had put up bail in that sum.

On election night, Bowron said in a radio broadcast:

“I know Los Angeles and the entire community can never be properly cleaned up without a new district attorney.”

Dockweiler had a proud name…but was, seemingly, a weak candidate in light of his virtual failure to make campaign appearances, his lack of prosecutorial know-how, and the appearance that he was under the domination of Clinton. Nonetheless, in the Nov. 5 run-off, Dockweiler amassed 779,221 votes, outdistancing Fitts who drew 516,929 ballots.

A Nov. 6 headline in the Examiner reads: “Dockweiler Wins in Weird Campaign.” The report, aptly summarizing the campaign, begins:

“John F. Dockweiler’s election as District Attorney over Buron Fitts climaxed a weird campaign in which a majority of forecasters had predicted Fitts’ reelection.

“Dockweiler, strongly supported by Mayor Fletcher Bowron, Clifford Clinton and organized labor, was content to make a few personal appearances and speeches.

“Fitts, on the other hand, made his usual strenuous campaign. He attacked Dockweiler as the mere ‘front man’ for Clinton, claiming that Dockweiler’s health made it impossible for him to be an active District Attorney.”

The newspaper quotes the DA-elect as saying: “I have only one boss, and that is myself.”

Given the political climate, it can be understood that a challenger such as Dockweiler—marginally qualified, at best, but waving a “reform” banner and embraced by the local symbol of reform, Bowron—would be preferred over an incumbent whose integrity was much in doubt.

![]()

Now that he had won, the Times ran a biographical profile on Dockweiler. Published Dec. 4, it begins: “John F. Dockweiler is a quiet, thoughtful man who wanted to be an actor but succumbed to what he says is the greater drama of politics.”

The article tells of Dockweiler’s ambition as a boy to become a thespian, but says his acting career came to take the form merely of a two-week stint as a bit player in a stage production. It goes on to say:

“Dockweiler, soft-spoken, courageous, and possessing a remarkable memory for names and faces, says he has no hobbies—‘unless reading, my pastime, is a hobby.’ ”

In the next column, I’ll discuss his term of office.

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOOTNOTE: Taplin denied the allegation that he had offered to sell his endorsement to Dockweiler, insisting that the charge was uttered to harm his chances in his bid for reelection in 1941. (Municipal court offices then appeared on the ballot at city elections).

Three days after endorsing Fitts, Taplin was visiting Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz when he experienced a heart attack, and was rushed to the hospital where his condition was declared “serious.” Taplin, who recovered, had apparently been under considerable stress. A story in the Examiner says that “Clinton admitted that he had met Taplin after he had endorsed Fitts and told Taplin that he had dictograph records of the conversation in which Taplin” asked for money in exchange for his support.

The Los Angeles Bar Assn. later investigated the charge as to Taplin’s conduct but did not announce a conclusion. However, the bar association made endorsements in those days, and in that context expressed its view of the incumbent. In its plebiscite, attorney Jack W. Hardy received 1,093 votes and Taplin got 973, with three other candidates drawing lower numbers. The bar association pushed for the election of Hardy.

The Times endorsed Harry G. Mellon, the candidate pulling the lowest number of votes in the bar plebiscite (258).

A Feb. 24 column in the Times takes on Taplin, as follows:

“Six of the Municipal judges have no opposition at all, but the lawyers sort of ganged up on Irvin Taplin and Orfa Jean Shontz. The old saw about perishment for those who live by the sword is being proved in the case of Judge Taplin. For years we couldn’t have an election without Irv running for something. Looked like he was after everybody or anybody’s job—City Attorney, Superior judge, District Attorney. Result, he’s regarded as a wild man, a menace to each and every officeholder, ready and eager to lay bold hands on the unwary. So officialdom will take this opportunity to hold a round-up on the wild steer, salt him and tin him.”

Taplin managed to gain reelection in the April 1 primary and remained on the bench until his retirement in 1964 after 32 years of service.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company