Tuesday, November 13, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

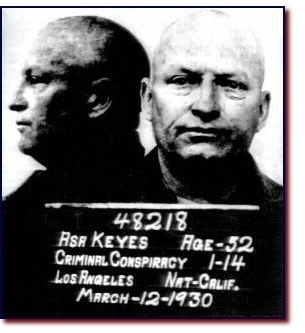

Ex-District Attorney Asa Keyes Becomes Prisoner No. 48,218 at San Quentin

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fifty-First in a Series

ASA KEYES, 28th district attorney of Los Angeles County, entered office on June 6, 1923. He gained the post because the DA who was exiting for health reasons, Thomas Lee Woolwine, had twisted supervisors’ arms to appoint Keyes, his trusted chief deputy. Keyes won the office at the polls in 1924, faced with only token opposition (by a Police Court judge). His term ended Dec. 3, 1928, when his elected successor, Buron Fitts, took over. In this period of roughly 5½ years, Keyes had gone from a skilled prosecutor, known for his honesty, and with a seeming future in politics, to a hobnobber with hoods, a lush, and a criminal defendant charged with taking bribes.

These were the days of Prohibition. Graft was rampant, just behind vice, often linked to it. Crooked politicians were hardly anomalies. But if there had ever before that time been a crooked Los Angeles district attorney, the facts of such corruption have never come to light.

There had been a mammoth swindle involving stock in the Julian Petroleum Corporation. “When all the losses were tallied, it turned out that 40,000 L.A. residents had been fleeced of $150 million,” according to Dennis McDougal’s 2001 book, “Privileged Son: Otis Chandler and the Rise and Fall of the L.A. Times Dynasty.”

A prosecution was brought against principals in that corporation. The 1928 prosecution failed; the trial judge publicly denounced Keyes for, in effect, throwing the match; hard evidence emerged that Keyes had accepted bribes to cause the acquittals.

This is the same Keyes who, in an Aug. 25, 1924 ad in local newspapers, placed by a local businessman, is hailed as “the ‘squarest District Attorney’ that ever held that office.” The entrepreneur adds: “I don’t believe ‘ten million dollars’ in his lap would make him violate his oath of office.” An ad the next day proclaims that Keyes enjoyed “a reputation for honesty…that no man would dare to question.” The advertiser was C.C. Julian, head of the petroleum company bearing his name. Oddly enough, Julian did not come to be charged in connection with the mega-scam.

On Feb. 8, 1929, a jury convicted Keyes and two co-conspirators on all counts.

(A lawyer defending Keyes was Paul Schenck, whom the volatile Woolwine had once belted in court.)

![]()

How many other bribes had Keyes taken? No others were proven, but….

•It was widely suspected that a payoff had induced his decision in January, 1927, to drop the prosecution of evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson for fabricating evidence.

•In the 1952 book, “Men of the Underworld: The Professional Criminals’ Own Story,” author Charles Hamilton tells of one Herbert Emerson Wilson, convicted while Keyes was DA of the murder of a cohort. Hamilton writes:

“His trial cost him $200,000, of which fifty grand went to District Attorney Asa Keyes, an abortive bribe that saved Wilson from the thirteen steps but sent him to San Quentin for life.”

(Wilson’s book “I Stole $16,000,000” was made into a movie, with Wilson being portrayed by Tony Curtis.)

•Hamilton tells also of James “Limey” Spencer, a hijacker of truckloads of illicit alcohol. He recites:

“A local crook, Niley Payne, hired Spenser as a bouncer for one of his gambling houses catering to ‘film stars, big business men, blackmailers, toughs, robbers, politicians, movie directors, professional killers, boxers, bunco men, and so on.’ Eventually Payne had a run-in with another gangster named Marco, and because the District Attorney, then Asa Keyes, was on Marco’s payroll, Spenser and his boss were framed and sent to prison. Before being released, after serving approximately four years, Spenser had the satisfaction of seeing the bribe-taking Asa Keyes join him behind bars.”

•Suspicions that Keyes had suppressed a prosecution of the slayer of movie director William Desmond Taylor were ignited by a report in the San Francisco Call-Bulletin on Dec. 21, 1929. It says that former Gov. Friend W. Richardson—who, while in office, had publicly denounced Keyes for untrustworthiness—had told the newspaper:

“I know who killed William Desmond Taylor. A motion picture actress killed this director, and I have positive proof to this effect.”

The former governor is quoted as saying that he garnered the information concerning the 1922 murder from an inmate at Folsom Prison, and related what he had learned to the foreman of the Los Angeles Grand Jury and the chair of the body’s criminal committee, but was told there was no chance of an indictment. Here’s Richardson’s statement to the newspaper:

“They explained that either Keyes or one of his deputies would be in the Grand Jury room and that before any person could be brought to trial for murder, the important witnesses would be spirited away, bribed or murdered.”

The former governor asserted that Keyes “stepped on the case.”

From his hospital bed at the County Jail where he was awaiting action on his appeal, Keyes issued a statement questioning why Richardson, if he had concrete evidence, had waited three years before making public mention of it.

![]()

Keyes had contended that his ill health mandated his release on bail pending resolution of the appeal. The Court of Appeal, on Aug. 14, 1929, rejected his motion. Although Keyes had bolstered his contention with the affidavits of five physicians and one dentist, the appeals court, in a 2-0 opinion (with one justice not participating), held that “an immediately imminent danger to appellant’s material well-being” had not been shown.

On Jan. 31, 1930, the Court of Appeal upheld the conviction, and the California Supreme Court on Feb. 27, 1930, declined to hear the case. (Well, it sort of declined. It issued a brief opinion in which it said “we withhold our approval” of the affirmance of Keyes’ conviction for conspiracy in connection with a bribe, explaining that someone who is bribed is guilty of the consummated offense of bribery. Inasmuch as the evidence showed that Keyes was bribed, and since the punishment for conspiracy and bribery were the same, the pleading defect was immaterial, the high court said.)

A Times editorial on March 1, 1930, is charitable toward a man it had frequently castigated, saying:

“For probably twenty of the twenty-five years during which Keyes was a public official, he deserved, and deserves, far more praise than blame. As a deputy District Attorney, under the direction of a superior, he was a good lawyer, an efficient, honest and able prosecutor, winning the friendship of those with whom he came in contact and the respect of the public. His elevation to command in the office where he had long been one of the chief supporting pillars was, it may now be seen, a tragic mistake. He acquired bad habits, neglected his work, fell in with evil companions, put his trust in subordinates who betrayed him, and at last his liquor-weakened moral fiber yielded under stress of temptation and he was lured to final destruction.”

The ex-DA was transported to state prison.

Time Magazine’s issue of March 24,

1930, reports:

Time Magazine’s issue of March 24,

1930, reports:

“In the five years he was District Attorney of Los Angeles Asa Keyes (pronounced Kize)…sent 4,030 men and women to California prisons for every variety of crime. Last week he joined this criminal company himself, entered San Quentin Prison as a convicted bribe-taker, a betrayer of public trust.

“ ‘What is life? We have an hour of consciousness and then we are gone,’ he grumbled as he entered the prison gates. Curtly, like any common thief, he was ordered to bathe, have his hair clipped short, be photographed, fingerprinted. As No. 48,218, he was put in a single cell in the ‘Old Men’s Ward’ by Warden James Holohan.”

The 1930 census shows him to have been a clerk in a lieutenant’s office.

![]()

On Dec. 18, 1930, Keyes was one of three convicts to address 50 Bay area law enforcement officers visiting San Quentin. The other two were Herbert Emerson Wilson and one-time middleweight prizefighter Norman Selby, known as “Kid McCoy.”

The former DA termed San Quentin “California’s training school for crimes,” a report in the Los Angeles Times says.

Keyes is quoted as commenting:

“I have only been here nine months, but as a convict I have learned far more about what is going on than any prison official or guard. Knowing things that I do, it is a genuine tragedy for me to see more young men sent here. Without facilities for proper segregation of prisoners, you are simply sending in new recruits for California’s growing crime army.”

Keyes was later to write to Gov. James Rolph urging that Selby, who killed his girlfriend, be pardoned, and also prepared an appeal to the governor that the sentence of an inmate who was scheduled to be hanged be commuted to life imprisonment. Both efforts failed.

![]()

Keyes had been sentenced to an indeterminate term of one to 14 years in prison. The parole date was to be set by the state Prison Board. The inmate petitioned for release after one year.

The backlogged board did not get to his application for a few months. On July 12, it set Keyes’ term at five years, the last two years to be spent on parole. With credits for good behavior, he was to be released in roughly three months.

On Oct. 13, 1931, Keyes left San Quentin. He had lined up a job in Los Angeles as a car salesman. The former DA could not practice law unless his civil disabilities were removed through a pardon by the governor—which Keyes had sought, and which wasn’t forthcoming—and until the California Supreme Court acted to readmit him.

A Times editorial published on the morning of his release protests:

“For the crime of accepting a bribe by a public official in so responsible a position, and upon whom so much of the public welfare depended, nineteen months of easy imprisonment, even though it followed thirteen months in the County Jail, is obviously inadequate.”

(The editorial includes this observation: “Los Angeles county has had some good district attorneys and some very poor ones; the average has been mediocre….”)

![]()

Keyes could not make a go of it as a car salesman. Nor as general manager of a bail bond company. He had, however, been proficient as a lawyer.

There was wide support for a parole in order to render Keyes eligible for State Bar reinstatement. District Attorney Buron Fitts, who prosecuted him, the judge who presided at his trial, the state’s chief justice, even the Times, backed the effort.

On Aug. 19, 1933, Rolph issued a pardon.

Prominent attorney Joseph Scott represented Keyes before the State Bar Board of Governors seeking its recommendation to the Supreme Court to reinsert the ex-prosecutor’s name on the roll of attorneys. But on Jan. 20, 1934, the board found, according to an Associated Press dispatch, that he “had not sufficiently rehabilitated himself in the eyes of the public to warrant” readmission. That effectively killed the bid for the time being. Keyes could reapply in two years.

But he didn’t live that long.

![]()

An Oct. 18, 1934, column in the Times by Harry Carr reflects:

“I used to go to school with Asa Keyes, who is reported to be near death as the result of a stroke. His was the greatest tragedy with which I ever came in personal contact. Asa was not a brilliant scholar: he was a careful, slow mind….In later years he turned out to be one of the finest trial lawyers ever to adorn our District Attorney’s office. There is something poisonous about politics; it poisoned him.”

Later that day, United Press transmitted a dispatch from Los Angeles which begins:

“Asa Keyes, 57, veteran Los Angeles district attorney who prosecuted some of the nation’s most famous criminal cases, and who was himself sent to prison as a convicted bribe-taker, died of a paralytic stroke today.

“His health broken by his conviction and the 19 months he spent in San Quentin, Keyes outlived his parole by less than three years....”

A column the following day in the Oakland Tribune reveals this:

“Keyes had been practicing law ever since he got out of San Quentin.

“You see when Keyes was Los Angeles’ district attorney he was very sympathetic to Hollywood’s problems. After he was released from the penitentiary, Hollywood sought to give him a helping hand. He began an automobile salesman and the stars, headed by Lew Cody, bought his cars.

“Then came the cycle of trial pictures and the men behind the gun had an idea. Why not let a real lawyer, like Keyes, play the losing lawyer in the court scenes. His voice was good microphone. He knew the legal phraseology. So Keyes made more than pin money, but his back was always to the camera. Only once did I see him turn. That was recently only for a fleeting instant.”

Next time: a look at Fitts, a DA who was indicted, who unsuccessfully sought the governorship, who eventually committed suicide.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company