Monday, October 1, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

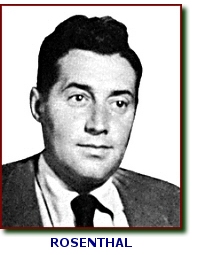

‘Uncle Jerry’—Jerome B. Rosenthal—Is Dead

By ROGER M. GRACE

I found out recently that “Uncle Jerry” died. Well, actually, Jerome B. Rosenthal was not still my uncle at the time he died—on Aug. 15, at the age of 96—and hadn’t been for some years.

He and my father’s sister, Ruth, were married in 1943, separated in 1959, and went through a highly contentious divorce that spawned three published Court of Appeal opinions. Despite wealth that Jerry accumulated, my aunt wound up with nothing...but was saddled with half the community’s debt to the IRS (which her subsequent husband paid off from his own funds). She died in 1994.

The Court of Appeal opinion upholding a $22.8 million judgment against Jerry in favor of actress/singer Doris Day, as well as the Supreme Court opinion disbarring him, tells something about what kind of guy he was.

![]()

Uncle Jerry was admitted to the State Bar of California on June 11, 1946. While some persons pegged him as a phony, to most he had charm. And he was bright, and cagey. Jerry became an attorney to the stars, and gained affluence.

Jerry was the subject of a June 9, 1948 column by United Press writer Virginia MacPherson. Jerry—whom she calls “a handsome young man with about 20 clients”—is credited with prowess in applying psychology, reconciling parties, and juggling clients’ finances. She writes:

“Hollywood lawyers hang gold-plated shingles reading ‘counselor-at-law’ outside their swanky offices. What that really means, one of the boys admitted today, is ‘nursemaid for movie stars.’

“ ‘You do a lot more than handle their divorces,’ Jerome Rosenthal sighed. ‘You’re a father confessor, a high-finance wizard, a movie critic, and a conscience.’ ”

![]()

Jerry and my aunt had sort of an upscale ranch house just outside the west entrance to Bel Air. At that time, the property included a swimming pool, a tennis court, and an orchard (and in all probability still does).

Every Sunday, they had a party, and their home was packed. Guests included the likes of George Murphy and Gordon and Sheila MacRae.

One time, a bunch of us kiddies was play-acting an adventure of “Rocky Jones, Space Rangers,” a TV show of the times. I had no idea that the nice woman who volunteered to play with us, assuming the role of the princess, was a famed singer: Margaret Whiting. (Jerry had represented her in a 1949 divorce action.)

Doris Day and my Aunt Ruth—“Pookey,” as she was nicknamed—were close friends. Then my aunt separated from Jerry. From that time, Day forgot that Pookey existed.

![]()

Jerry

had represented Day since

the late 1940s. He was her attorney in her 1949 divorce action against her

second husband, George W. Weidler. (In her “autobiography”—actually a biography

by A.E. Hotchner written in  the first person—Day relates running into a man in

1969 in Beverly Hills who asked if she remembered him. When she responded in

the negative, he remarked: “Well, you didn’t have that many husbands.”

It was Weidler.)

the first person—Day relates running into a man in

1969 in Beverly Hills who asked if she remembered him. When she responded in

the negative, he remarked: “Well, you didn’t have that many husbands.”

It was Weidler.)

Actress Marie Wilson hired Jerry to file a divorce action for her in 1950. She was granted a divorce…but in Las Vegas. A Dec. 30, 1950, article in the Times says:

“Marie Wilson, radio and film actress, won a Las Vegas (Nev.) divorce yesterday from Allan H. Nixon, actor, on a ‘minute-a-day’ gimmick.

“Although Miss Wilson fulfilled the six-week residence necessary for a Nevada divorce, she spent one day a week in Hollywood to do her radio show.

“This was possible, her attorney, Jerome Rosenthal, explained, on the basis of a ruling that a person need spend only one minute of each required day of residence in the State.”

My then-uncle brought suit in 1950 against actress Betty Grable on behalf of a talent agency, MCA, when the WWII pin-up girl terminated its services. He also represented MCA in a 1951 action against actress Joan Fontaine.

From the Times (Feb 16, 1951), TV columnist Walter Ames writes:

“Those eastern television brains, who have been feeding West Coast viewers poorly engineered kinescopes [films of live TV shows shot off a monitor] and making us like them, have apparently realized our position as the second highest audience in the country.

“The soft-drink firm handling shapely Faye Emerson has called Jerome Rosenthal, legal light of United Television Programs, East for a conference designed to button up a deal to produce 132 Emerson shows on film for release throughout the country.”

The prospect became a reality. Hedda Hopper’s nationally syndicated Feb. 17, 1951 column says that Emerson’s sponsor (Pepsi-Cola) was converting a warehouse into a sound stage to film her shows…noting: “Jerome Rosenthal, lawyer, set the deal.”

![]()

Jerry represented John Wayne’s second wife, Esperanza—known as “Chata”—in a separate maintenance/divorce action.

On May 18, 1953, the lawyer argued that, based on the actor’s gross annual income of $502,891, temporary monthly support should be set at $9,350, rather than the $900 offered by Wayne.

One inventive approach by Jerry resulted in this headline in the Long Beach Independent on May 26: “Claim Wayne Should Pay Ma-in-law ‘Alimony.’ Below was an Associated Press dispatch reporting that Rosenthal sought court-ordered support payments by Wayne to his wife’s mother on the ground that the wife paid $650 to her mother each month with her husband’s consent, so that this was a normal household expense.

The article says:

“Wayne’s attorney, Frank Belcher [a former Los Angeles Bar Assn. president and past State Bar president], jumped to his feet and declared he knew of no case where the courts had required a man to support his mother-in-law after a divorce.

“Superior Judge William R. McKay said: ‘I want to hear all about this, as this mother-in-law situation frequently is the crux of a divorce contest.’ ”

After hearing all about it, McKay rejected the contention.

My father (who died in 1974) did something once that John Wayne desisted from doing during that litigation. Dad belted Jerry, knocking him down. It happened sometime around 1958, at one of the Sunday parties. The flap had something to do with an improper gesture by Jerry. I was about 13 at the time and the details weren’t imparted to me. I understand that the decked Uncle Jerry ordained that my father never darken his door again. Dad and Jerry did not again cross paths.

Wayne was tempted to belt Jerry in court, but held back. The 1997 book “John Wayne: American,” by Randy W. Roberts and James Stuart Olson, tells of this incident during the 1953 proceeding:

“Duke struggled to keep his temper. During the temporary maintenance hearing, Jerome Rosenthal, who had replaced [Jerry] Giesler as Chata’s attorney, suggested that he could ‘prove that John Wayne is a liar,’ that he hid income and that he used all sorts of tax dodges, including having RKO pay for his vacation in lieu of part of his salary and writing it off as a publicity campaign. Duke’s face turned red and he smashed his fist on the court’s railing, made a move toward Rosenthal. then rushed out of the courtroom.”

I’m reliably informed that Wayne did, however, have occasion to slug Jerry in the parking lot of Chasen’s (a fashionable restaurant, now the site of a market).

In 1955, Jerry represented actress Ann Sothern (star of TV’s “Private Secretary”) in attempting, unsuccessfully, to acquire television rights to the character she portrayed in a series of films and on radio, Maisie.

![]()

Jerry and his law partner, Sam Norton, in 1955 sued a former client, Hedy Lamarr, for $18,215 in unpaid attorney fees. She cross-complained for $25,066.24, contending that amount to be what she overpaid the lawyers.

Trial was scheduled for Sept. 10, 1957, but a last-minute settlement was reached, on undisclosed terms.

Jerry was to sue other clients—including Day—in the years ahead, as a preemptive strike. It didn’t work.

Highly speculative investments he made for clients—and into which he also poured funds belonging to him and Aunt Pookey—failed. The party boy of the 1950s became a fulltime litigant in the 1960s…that litigation including my aunt’s divorce action.

![]()

The first published opinion in that case was handed down Nov. 24, 1961. Jerry had appealed from three separate interim orders by three judges. The orders dealt with temporary support and attorney fees. The opinion by Justice Allen W. Ashburn begins:

“Three appeals are presented concurrently in this divorce action. Since March, 1959, the parties have engaged in spirited litigation which, so far as the record discloses and as was conceded upon oral argument, had not yet eventuated in an interlocutory judgment.”

Ashburn notes:

“There have been three previous appeals by defendant from orders made in this cause, two applications in the District Court of Appeal for prohibition and one for mandamus, all of which special writs were denied.”

After dealing with Jerry’s various contentions—including the existence of a conspiracy among Aunt Pookey and her attorneys, and supposed error in not ordering one of her lawyers, Arthur Crowley, to produce his checkbook stubs—the jurist remarks:

“The records of these three appeals disclose that the respective trial judges were acutely conscious of appellant’s persistently technical and dilatory opposition to plaintiff’s motions and of his recurring offensive conduct and language toward the judge. Everything considered, each of these judges was patient beyond the call for equanimity and impartiality….”

The second published opinion, filed March 21, 1966, accepts some of each party’s contentions, rejects others. With respect to Jerry’s objection to the appointment of a receiver to liquidate assets, Justice Macklin Fleming says: “Liquidation of the community estate was not entrusted to then husband because, although he was earning over $100,000 a year from his law practice, he insisted on pouring large amounts of money into community oil speculations, thus draining the community estate of its assets with little chance of profit in the foreseeable future.” The appointment of a receiver, Fleming says, was reasonable.

In the appeal disposed of March 4, 1969 in the third published opinion, Jerry wanted to just ignore the second opinion and have the matter remanded to the trial court. “These appeals constitute an attempt to assert an improper collateral attack on a judgment which has become final,” Justice Walter Fourt writes.

![]()

Those speculative investments, as I mentioned, fizzled. In her 1976 book, “Doris Day, Her Own Story,” Day mentions:

“By far the worst Rosenthal-related incident involved the beautiful actress Dorothy Dandridge, who killed herself a few years ago, shortly after her agent called to tell her that he had checked on certain investments which her lawyer, Jerome Rosenthal, had made for her, and had discovered that she was penniless. Of course, she had no money to sue Rosenthal; not very long afterward she had committed suicide.”

(Jerry was quick to sue Day for $20 million for statements she made about him in her book, but the action got nowhere.)

Ross Hunter, who co-produced three Doris Day movies, had a case against Rosenthal that was in trial at the same time as Day’s action. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge James Tante awarded him $400,000, based partly on shoddy investments, but found that Hunter owed Jerry $150,000 for services.

![]()

The Hotchner/Day book is interspersed with comments by third parties, in a different font from the portion attributed to Day. Terry Melcher, Day’s son by her first marriage, tells of a confrontation with the man he had known as a child as “Uncle Jerry.” It was 1968, step-father Marty Melcher had died, and, as administrator of the estate, he learned that CBS had made a $500,000 advance to his mother for her upcoming role in “The Doris Day Show.” (Marty Melcher had committed Day to do that series without her knowledge.) Where was the half million dollars? Terry Melcher (who died in 2004) provides this account of the conversation:

“You ask too many questions,” he said. “Go home, Junior, and let me take care of this. Don’t worry. I’m running things, just leave everything to me. Now go on home.”

“That’s your answer?”

“That’s it. When I need you I’ll send for you.”

“Well, Jer, I’ll tell you how it is—you’re fired.”

Day quotes Terry Melcher as breaking the news to her of what he had uncovered:

“Mom, these past four days, I’ve had a showdown with Rosenthal, and the bad news is—God, I wish I didn’t have to tell you—but the fact is, you don’t have anything. Not a penny. The hotels are bankrupt, all the oil wells are dry, and there aren’t any cattle. Nothing, Mom, and what’s even worse, you have a lot of debts—like around four hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Most of it is taxes. They have to be paid. You may have to sell this house.”

In a future column, I’ll get into Day’s action against Jerry, the disbarment proceeding, and Jerry’s jailing for contempt. But first, I’ll return Wednesday to the tale of onetime District Attorney Asa Keyes.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company