Tuesday, July 3, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

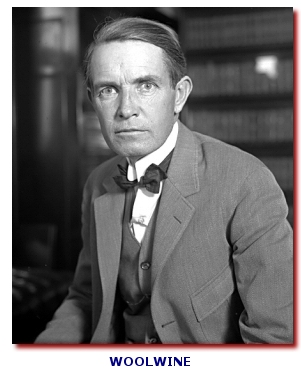

Woolwine Dies…Remembered as ‘Stormy Petrel of State and County Politics’

By ROGER M. GRACE

Forty-Second in a Series

THOMAS LEE WOOLWINE, the 27th district attorney for Los Angeles County, died on July 8, 1925 after battling a debilitating liver disease for two years. There was a stream of accolades—praise for his integrity, his pluck, his intellect—but there was an underlying awareness that Woolwine had been a man marked by constant controversy, engendered by his combative nature.

An obituary in the Los Angeles Times which appeared the morning after his death observes:

“Mr. Woolwine was the stormy petrel of State and county politics for many years. His resignation on June 6, 1923, closed one of the most spectacular careers in the history of State politics, a career which, among district attorneys was said to have attracted more nation-wide attention than that of any other prosecutor with the possible exception of Dist.-Atty. [William Travers] Jerome of New York….”

Woolwine craved attention and thirsted for advancement. In 1918, he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for governor; in 1922, he attained the nomination, but lost in the run-off. Woolwine might, despite those losses, have attained higher office had ill health not intervened, resulting in his death at the age of 50.

![]()

Here’s a run-down of Woolwine’s last six years in office, gleaned from reports in the Times.

1918

Feb. 5: Announces his candidacy for the Democratic nomination for governor.

April 27: Declares that anarchists “should be quickly and effectively muzzled for the duration of the war.”

June 5: Declines to take a stand on national Prohibition, explaining in San Francisco: “There is no liquor measure before the people over which the Governor will ever have jurisdiction to either approve or veto it. Therefore, the liquor question is not and cannot be an issue in the gubernatorial campaign.” He adds: “Any declaration on the prohibition question by any candidate can be for but one purpose, and that is a cheap bid for votes at a time when prohibition measures have become popular.” Four years later in running for governor, at a time when national Prohibition was in effect and wasn’t popular, Woolwine was to make a cheap bid for votes by advocating a loosening of the liquor ban.

Sept. 18: Publicly accuses Sheriff John Cline of fixing speeding tickets for those with “political or other influence.” (Cline is removed from office in 1921 in proceedings instituted by County Counsel A.J. Hill.)

Aug. 27: Comes in third in the Democratic gubernatorial primary.

1919

April

30: Cross-examines Los

Angeles Mayor Frederic Woodman, a defendant charged with soliciting and

accepting a bribe. The Times reports the next morning that Woolwine “made a

determined but apparently futile attempt to shake” the mayor’s story.

Representing the mayor is the man Woolwine challenged in the 1910 race for

district attorney, then-incumbent John D. Fredericks.

attempt to shake” the mayor’s story.

Representing the mayor is the man Woolwine challenged in the 1910 race for

district attorney, then-incumbent John D. Fredericks.

May 2: Loses the case against Woodman, who is acquitted by a jury after three hours of deliberation. (SIDE NOTE: The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office website says that Woolwine “contribute[d] to the downfall of two mayors, Charles Sabastian [sic] and Frederick [sic] Woodman.” Woolwine had prosecuted Sebastian in 1915. Charged with immoral conduct involving a 17-year-old girl, the defendant was, at the time, chief of police and a candidate for mayor. Trial began April 14; Sebastian was acquitted on May 14, an event sparking a massive celebratory parade; and he won the election on June 1. His downfall was not, in any way, brought about by Woolwine. Following publication by the Los Angeles Record of an embarrassing letter relating to Sebastian’s personal life, the mayor resigned on Sept. 2, 1916, for “health” reasons. As to Woodman: if Woolwine did contribute to his defeat, it was only indirectly. Woolwine’s prosecution of Woodman, as just noted, failed. The fact of the prosecution did not prevent Woodman from garnering 19,504 votes in the primary, second only to the 23,368 ballots casts for Meredith Pinxton “Pinky” Snyder, who had three times before been elected mayor. The tally provided optimism for the Woodman camp since the candidate placing third in the six-way race, businessman Sylvester Weaver, drew 13,864 votes. Nonpartisan though the office is, it seemed likely that votes garnered by Sylvester in the primary would go in the run-off to the Republican Woodman (whom Sylvester endorsed) over the Democrat Snyder. But there were intervening events such as the resignation of Woodman’s secretary and his public assertion that Woodman had instructed him to lie under oath before the grand jury. Woodman lost the run-off on June 3, 1919 by a vote of 26,779 for Snyder and 15,578 for him, with any causation of the outcome by Woolwine being quite remote.)

1920

May 25: Announces he is a candidate for re-election.

Aug. 15: An anti-Woolwine ad appears in the Times bearing the signature of Fredericks and others. It quotes Woolwine as saying in a June 10 address before the convention in Los Angeles of the District Attorneys Association of California: “My motto is, if a fellow is a thief and a grafter, and you can’t convict him, mess him up so that he will not be able to walk the streets.”

Aug. 31: Wins easy reelection in the primary over Charles W. Lyon, city attorney of Venice.

1921

Feb. 14: Is ridiculed in open court by Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Frank R. Willis after the jurist looked over Woolwine’s opposition to a defendant’s motion for a continuance. The opposition says: “The law’s delays are calculated to foster anarchy and disrespect for constituted authority. Here is an infamous crook and scoundrel that I have sought to bring to trial for ten months.” Willis blurts out, sacrastically: “It is too bad that we can’t abolish courts altogether so that when the District Attorney has a man arrested he can be brought before the District Attorney, bow three times and kneeling in humble supplication say, ‘Oh, lord and master, give me my sentence—however you wish it.’ Why not abolish courts, judges, juries and lawyers; just have the District Attorney sentence the men when they are arrested? And if Woolwine should go back to New York for a few months, why not give him power to delegate his authority to the Sheriff, for the Sheriff to take every person to San Quentin as soon as arrested and without a fair and impartial trial?” The defendant gets a one-month continuance.

Sept. 30: Is severely castigated in a report by a grand jury committee, accusing his administration of being a “carnival of extravagance, waste, inefficiency and corruption.” The full grand jury calls for a state investigation of Woolwine’s office.

Oct. 6: Releases a press statement remarking that the state attorney general, in deciding to take no action in response to the grand jury’s request, “refused to be misled” by “character assasins.” He asserts: “The action of the committee of the grand jury that met in secret session without giving any member of the District Attorney’s office an opportunity to be heard, and attacking me while 3000 miles away on official business, was diabolical.”

Oct. 24: Objects to a motion that Chicago lawyer Charles Erbstein be permitted to represent a defendant in a murder case here, referring to him as “a trickster, a jury fixer and a suborner of perjury.” Erbstein had been twice indicted on, and acquitted of, charges. The Chicago lawyer tells Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Sidney N. Reeve that Woolwine was pulling “a dirty, dastardly, unheard of, unknown of, contemptible trick.” Reeve refers the matter to the Los Angeles Bar Assn. for a report and recommendation to him.

Nov. 2: Faces the possibility of an action in the Superior Court to remove him from office. The Los Angeles Times that day reports that the president of the Los Angeles Bar Assn., Frank James, confirmed receipt of a request from the grand jury to file an accusation under (then) Penal Code §772 alleging a failure of the DA to perform his duties as required by law. A judge was empowered under that section to oust a public official if the allegations were sustained. (Woolwine had beaten off such an action filed against him in 1916.)…That same morning, Reeve grants Erbstein pro haec vice status following receipt of a report from the bar association vouching for him.

1922

Feb. 21: Is in New York investigating the much-publicized slaying in Los Angeles of motion picture director William Desmond Taylor. The New York Telegraph scoffs: “The police and the fame-seeking District Attorney of the California metropolis apparently have questioned persons who had no more to do with Taylor’s murder than the residents of the Canary Islands. One Woolwine, District Attorney, made what he called an independent investigation, with a camera-man tagging him around and reporters in his following.” This brings to mind City Prosecutor Woolwine’s raid of the California Club in 1908 (based on his soon-to-be-discredited view that the private club needed a saloon license), with reporters and photographers trailing behind him.

April 1: Says he might resign as DA to devote himself solely to seeking the governorship, commenting to a reporter: “It would be marvelous to be Governor of California if one could go there free from the chains of political chicanery and disgusting combinations which are sometimes demanded of a candidate for office.” He stresses that he harbored “no serious intention of running for Governor.”

May 30: Enters the race for the Democratic nomination for governor; doesn’t resign as DA.

Aug. 25: Fails to secure a conviction of 35 members of the Ku Klux Klan on trial in connection with their raid of a home in Inglewood, the occupants of which were suspected of engaging in illegal liquor sales. Though he had contemplated personally trying the case despite his campaign, he wound up leaving it in the hands of his chief deputy, Asa Keyes.

Aug. 29: Vies with four others in an open primary, including an obscure Glendale attorney, Mattison B. Jones, who competes with him for the Democratic nod while also seeking the Prohibitionist nomination. Also on the ballot are a Republican, a Socialist, and man seeking to be both the GOP and Prohibitionist candidate. Woolwine bags the Democratic nomination, and will face Republican Friend W. Richardson and Socialist Alexander Horr in the run-off.

Sept. 19: Proclaims Prohibition a “stupendous failure” and proposes amending the Volstead Act to permit the manufacture and consumption of light wines and beers—a stance to be denounced in both Democratic and Republican quarters, and not mentioned in the Hearst newspapers, including the Los Angeles Examiner, which were fervently backing him. Woolwine apparently is not called upon to reconcile his new campaign isue with what he said on June 5, 1918, as to the irrelevancy of the Prohibition issue to a contest for the governorship.

Nov. 7: Suffers defeat at the polls, with the Republican candidate, state Treasurer Friend Richardson, attaining 228,915 more votes.

Nov. 22: Lashes out at a group of ministers planning an effort to recall him based on his desire, announced during his gubernatorial campaign, to see light wine and beer legalized. “Within the last few days I have been subjected to the most unjust, high-handed and despotic series of attempts at intimidation and bullying with which I have ever come in contact,” he declares. In the course of a lengthy statement, Woolwine goes on to say: “I have always had the greatest regard and respect for the truthful, God-fearing, conscientious, sane minister of the Gospel, but I have no regard, respect or admiration for advertising hypocrites and publicity seekers. They might better spend their time in some charitable attempt to uplift the forsaken of this earth than to denounce and crush down the duly authorized officers of the law, who are conscientiously trying to do their duty. [¶] Whether they know it or not, they are backed by a band of character assasins and unscrupulous politicians, who would wreck the county of Los Angeles to see me out of office. I have never been controlled by any man or set of men, whether they be ministers, confidence men, crooks or character assasins, and I do not propose to change my way nor yield to them one iota.”

Nov. 23: Is sued for libel by a former investigator in his office, Ida Jones, based on two statements by him, which were published by a newspaper. One statement, issued May 31, read: “This woman was discharged by me when I discovered that she had declared her intention of selling to my political enemies for $10,000 an affidavit falsely accusing me of being intimate with her.” A later comment was that his enemies were hiding behind the “soiled skirts of this vicious, common woman.” Jones is seeking $50,000. Her version is that Woolwine fired her when their affair broke up in order to discredit her, in case she was set on tattling to his wife. (The story is to end after Woolwine’s exit from office with Los Angeles Superior Court Judge John M. York granting a nonsuit on March 20, 1925, finding that Woolwine’s comments were privileged.)

1923

June 6: Submits his resignation as district attorney to the Board of Supervisors which proceeds to choose as his successor Asa Keyes, his chief deputy. He says in a written statement provided to the board: “I have been informed by several physicians that to remain in office under the strain necessarily incident to my official duties might result in my death and certainly would make it impossible for me to ever recover. On the other hand, I am informed that, if I lead a quiet life, free from care and worry, my restoration to health would be assured, owing to my strong constitution.” (He is to convalesce in Europe for about a year before returning to Los Angeles.)

![]()

I’ve referred to Stephen M. White as having been “probably the most illustrious of the men who have served as Los Angeles district attorney” and J.R. Dupuy as “the most obscure DA in the county’s history.”

Among the past district attorneys of Los Angeles County, Woolwine, too, stands out. He was not the best, not the worst, but was surely among the most noticed.

Of all the DAs of this county, Woolwine clearly was the most controversial, the most complex, the most enigmatic...in some ways worthy of respect, in others, deserving of disdain. He was a seeker of justice, a defender of honor (even to the point of threatening a neighbor with a pistol because his dog attacked Woolwine’s dog). He was the author of a 1912 romantic novel, a sensitive man...an impressive orator…a deft and brilliant lawyer...a publicity-seeker...and, at times, a jerk.

Next: a look at Woolwine’s successor, Keyes. While Woolwine was convicted of misdemeanors during his time in office and fined, Keyes topped him; he was convicted of a felony—bribery—and sent to prison.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company