Monday, June 11, 2007

Page 15

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Woolwine Prosecutes Jevne, Others Over the Price of Bread

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fortieth in a Series

THOMAS LEE WOOLWINE, district attorney of Los Angeles County, in 1917 turned his personal attention from murderers and rapists, and focused on a vile and dangerous band of miscreants…the bread bakers.

The DA’s efforts became devoted to punishing the heinous deeds of those who wanted to set a 15-cent price on loaves of bread sold to consumers. They were prosecuted by the DA with fervor in the case of People v. H. Jevne Company.

While I’m obviously being facetious as to the seriousness of the offense that was charged, the wholesale bakers of Los Angeles did commit a seeming no-no. They had gotten together and agreed to sell standard 24-ounce loaves of bread to retailers at 12 cents each, and to require that the retailer, in turn, sell the loaves to consumers for at least 15 cents each. And, if a grocer set the price lower than that, he just wouldn’t get future shipments of bread.

Price-fixing was, in general, a violation of the state’s Cartwright Act, enacted in 1907. However, the bakers thought that an exception, enacted in 1909, protected them. It said that trusts were forbidden “[p]rovided that no agreement, combination or association shall be deemed to be unlawful or within the provisions of this act, the object and business of which are to conduct its operations at a reasonable profit or to market at a reasonable profit those products which cannot otherwise be so marketed.”

It was critical to boost the price of bread, they declared, because of the soaring cost of flour and other ingredients.

The accord among the bakers was reached at an April 26 meeting in the Douglas Building, on the northwest corner of Third and Spring Streets in downtown Los Angeles. Representing H. Jevne Company was its vice president, Jack Jevne—whose participation resulted in him becoming an individual defendant in Woolwine’s action, along with the company. That company and its founder, Hans Jevne (Jack’s father), have been the subject of a series of my “Reminiscing” columns. The H. Jevne Company was the original occupant of the space at 210 S. Spring Street where the operations of this newspaper are now based.

![]()

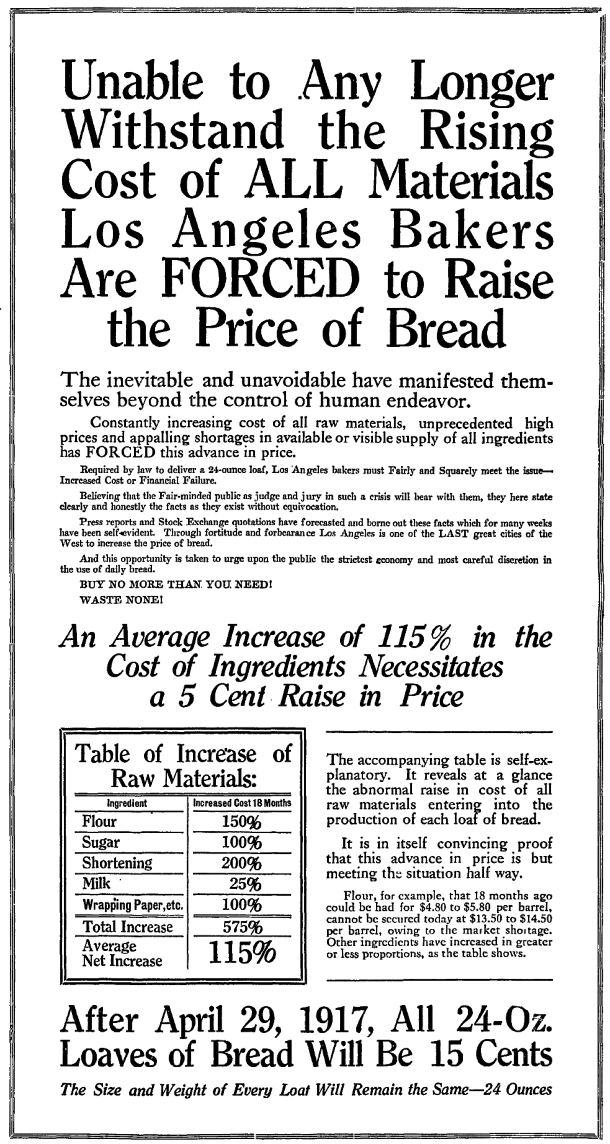

The bakers were not sneaky about the existence of an industry-wide accord. The wholesalers each chipped in to buy newspaper ads announcing:

Grocers were quick to complain to the District Attorney’s Office about the price-fixing, and Woolwine brought the matter before the Grand Jury on May 7.

On May 18, an indictment was handed up charging 11 companies and 16 individuals with restraint of trade.

The indictment did not charge the bakers with price-fixing in connection with their agreement that 12 cents would be the wholesale price, but only in connection with their pact to dictate the retail price.

The maximum penalty for individuals was a year in jail and a $5,000 fine…and for corporations it was forced dissolution and a $5,000 fine.

The Los Angeles Times’s May 19 report says:

“The indictments represent the first effort by a Los Angeles District Attorney to invoke the Cartwright anti-trust law in remedy of a commercial condition. By reducing the price of bread one and one-half cents a loaf, Dist.-Atty. Woolwine considers he will be saving the bread-eaters of the community $150,000 daily.”

I have no idea how Woolwine’s success in the action would have resulted in consumers being able to buy bread for 13˝ cents.

It is understandable that there had been no previous prosecutions by the DA’s Office under the 10-year-old statute. A violation was but a misdemeanor—and all misdemeanors committed in the City of Los Angeles were prosecutable by the city attorney in Police Court. In smaller cities, “high” misdemeanors—such as antitrust violations—were prosecuted by the DA in Superior Court. Woolwine got into Superior Court by virtue of allegations that acts in furtherance of the conspiracy were taking place outside of the City of L.A.

![]()

The Times’s article on May 19 quotes a “high official of the H. Jevne Company, who asked that his name not be used,” as saying:

“I am glad to hear that we are indicted; now the real facts will be brought out. We are not restraining trade in any way. We are selling bread at less than cost. Los Angeles is the only place in the United States where bread is so cheap. You cannot buy bread as cheaply in New York or Chicago. The prices of materials are so high in Los Angeles that I have heard that sixty small bakers have gone out of business. I sympathize with the small bakers who have lost money and have had to close up. There is no combination to fix prices that I know of. We put a price on our bread and if people do not want to buy it for that, they can buy it somewhere else.”

A petition was filed in the California Supreme Court on Aug. 18 for a writ of prohibition to block the trial, but the bid failed.

Woolwine personally conducted the prosecution.

Testimony began on Sept. 25 with the identification of the persons who attended the meeting at the Douglas Building, rendered by a wholesaler who was present but did not vote on the price-setting proposal. (Testimony recited below comes from accounts in the Times and the Examiner.)

The witness, John C. Stockwell, related a conversation earlier with Walter B. Ralphs, president of Ralphs Grocery Company, concerning a proposed hike in bread prices. Ralphs was quoted as saying:

“You bakers can make the wholesale price of bread anything you see fit. I will fix my own price.”

Ralphs was a witness the next day. He said he was told by one of the defendants that if he did not maintain a price of 15 cents a loaf at his stores—he then had five of them—there would be no more bread deliveries.

Woolwine unexpectedly concluded his case on Sept. 28.

Through testimony on Oct. 2, the defense sought to show that in raising the price of bread, the bakers were merely doing what the City Council told them to do. They thought an answer to the burgeoning costs would be to maintain the existing price, but reduce the size of loaves—except that a requirement that loaves be 24 ounces had been imposed by ordinance. George H. Barnes of Faultless Bread Bakery recalled:

“We went to the Council with a petition to get the weight ordinance recalled. This petition was turned down. The Council told us the only way to do was to get together and raise the price.”

Under cross-examination by Woolwine, Barnes maintained that the persons attending the April 26 meeting did not pass a resolution to set the price of bread—they merely expressed their individual views that a 12-cent wholesale price and a 15-cent retail price were “reasonable.”

![]()

On direct examination on Oct. 2, Jack Jevne said that the cost of manufacturing a 24-ounce loaf of bread, as of April of that year, was 12.57 cents. (Had the bakers, in fact, boosted the wholesale price to a level where they were still losing money?)

While the wholesalers had an obvious need to raise the wholesale price, the need to dictate the retail price was not clear. Asked on cross examination by Assistant District Attorney William C. Doran to explain, Jevne said:

“It was of vital importance to the whole baking industry what price Mr. Ralphs charged. Mr. Ralphs’ cutting the price of bread meant the tearing down of large baking institutions which we were trying to build; it meant ruin to many, for only by upholding the retail price could the wholesale price be maintained.”

Doran later queried:

“Do you mean to say that a few individual retailers, possibly handling 2 per cent of the entire output of bread, could by cutting the price have had an effect on the other 98 per cent of the retailers?”

Jevne responded:

“To a large extent. The cutting of the price would lead the public to think that these dealers were buying bread for a lower price than the others. The public would not understand and would condemn the bakers.”

What? The bakers had to strong-arm grocers into charging 15 cents a loaf because if any of them charged less than that it would mean bad PR for the bakers?

![]()

Conviction came on Oct. 11. The jury deliberated for less than an hour. Woolwine declared in a press statement:

“The conviction of the bread trust is a victory for the people with far-reaching results, and it would have been nothing less than a disaster had the verdict been otherwise. It will not only have its effect in the county of Los Angeles, but will constitute a warning to food speculators of all kinds throughout the State of California. This is, as I am informed, the first real test of the effectiveness of the so-called anti-trust law, although it has been on the statute books ten years.

“It is fortunate indeed that the people were able to secure a courageous and conscientious jury in this case, who did not hesitate to do their duty where great and powerful interests were involved.”

Woolwine decried the practice of “cornering food stuffs” and stifling competition so as to render “the necessaries of life so costly as to be beyond the reach of the poor,” adding:

“For in the last equation, the people are the ones who are made to suffer want and privation, while those possessing positions of affluence and wealth further enrich themselves by such unlawful practices.”

The district attorney did have a flair for melodrama.

![]()

Houser fined nine companies and one individual who hadn’t incorporated $1,000 each, and fined Jack Jevne and 11 other individuals $100 each.

The District Court of Appeals affirmed; the California Supreme Court did the same on Jan. 28, 1919, in a unanimous decision.

Justice M.C. Sloss wrote:

“It is to be remembered that the defendants are wholesale dealers in bread. They are charged with combining to fix, not the price which they, as such wholesalers, were to receive for their product, but that to be obtained from the ultimate consumer by the retailers to whom they sold. The proviso added to the statute authorizes an agreement or combination with the object of conducting its operations at a reasonable profit, or marketing certain products at a reasonable profit. This provision manifestly contemplates a profit sought by the persons entering into the combination, not the profit of their customers or vendees. As applied to the case at bar, the amendment goes no further than to authorize wholesale dealers in bread to combine for the purpose of realizing a reasonable profit in their own dealings. It does not assume to legalize a combination or agreement entered into by them with the object of securing a reasonable profit to the retailers who may buy from them.”

![]()

This column is today entering its 35th year. It started out in 1973 in a newspaper that had its headquarters in Jevne’s old space at 210 S. Spring Street, the Daily Journal.

While here, the company that owned the newspaper was socked with two actions under the Cartwright Act, one which it won, the other which it settled, with a $1.6 million payment and an agreement to divest itself of the Journal.

And, while here at 210 S. Spring Street (since 1990), the Metropolitan News Company brought an action against the Daily Journal Corporation for anti-competitive conduct, not under the Cartwright Act, and lost.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company