Tuesday, April 3, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Fredericks Gains Convictions of Both McNamara Brothers

By ROGER M. GRACE

Thirty-First in a Series

JOHN D. FREDERICKS, having beaten off a vigorous election challenge in 1910, encountered a greater challenge in 1911: gaining a conviction of the McNamara Brothers, John and James, charged with having dynamited the Los Angeles Times Building.

That act of terrorism, occurring at about 1 a.m. on Oct. 1, 1910, reduced the building to ruins and caused the deaths of 21 persons (one of them dying days later in the hospital). The McNamaras were union loyalists; the Times had an open shop and was, editorially, hostile to the unions.

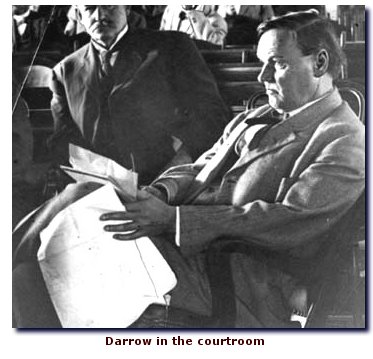

Fredericks was lead prosecutor, and the main defense lawyer was the famed Clarence Darrow.

![]()

Fredericks decided to try the brothers separately, starting with James B. (or “J.B.”) McNamara, the younger brother, against whom the evidence was solid. After jurors were sworn but before testimony, the duo changed their pleas. While voir dire was in progress, so were negotiations.

The defendants agreed to plead guilty after their cause—or at least that of the younger brother—was rendered hopeless by the confession of a co-conspirator, as well as damning documentary evidence obtained in Indiana through a search of the headquarters of the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers. That search occurred on Oct. 12, 1911, at the instance of no less than the president of the United States.

As told by historian W.W. Robinson in his 1969 book “Bombs and Bribery,” Fredericks “needed further proof” of the veracity of the confession, but couldn’t get hold of it. Then, Robinson says, there came the break-through: President William Howard Taft, while in Los Angeles, engaged in a “secret meeting” with Otis and with Oscar Lawler (former assistant U.S. attorney general under Taft, recently enlisted by Harry Chandler, son-in-law of Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis, to back up Fredericks in the prosecution). Robinson interviewed Lawler (the 1923 Los Angeles Bar Assn. president) on Sept. 3, 1959. According to Robinson’s recitation of what he learned:

“Lawler persuaded Taft, in the interests of justice, to provide federal aid, first assuring him that violation of federal law had taken place. The next day federal officers, under Attorney General [George W.] Wickersham’s orders, entered the Indianapolis headquarters. They found the overwhelming evidence needed by Fredericks: not only dynamite, clocks, and fuses, but the tell-tale correspondence and clippings that backed up the confession as it related to the dynamitings in Los Angeles and to the country-wide conspiracy involving the men who composed the national dynamiting syndicate.”

Robinson (author of the book “Lawyers of Los Angeles,” often quoted here), says in “Bombs and Bribery” that an attorney for the defense, LeCompte Davis, “was the intermediary between Darrow and District Attorney Fredericks—with considerable jockeying going on about the form of the pleas.”

![]()

Robinson’s book, of which only 300 copies were printed, quotes from the up-to-then unpublished account by Otto F. Brant, who had been general manager of the Title Insurance and Trust Company, of his role in the plea negotiations. Robinson terms Brant a “close friend and associate of Chandler and a potent behind-the-scenes influence in Los Angeles business circles.” (Brant, Chandler and Otis were among five men who owned the company that subdivided the San Fernando Valley. Chandler went on to become the Times’s publisher from 1917-44.)

Brant is quoted as recalling that Chandler called on him a “week or ten days before Thanksgiving” and asked that he assist in resolving the criminal proceedings against the McNamaras. He agreed and, according to his account:

“I telephoned to District Attorney Fredericks and asked him to come to my office, which he did within a very short time. Upon the arrival of Fredericks (Chandler being present) I asked him if he would receive a confession of J. B. McNamara and dismiss all other actions. He said, ‘Most emphatically, no. I am of course willing to settle this matter but it will have to be on a different basis than that.’”

Brant’s account goes on to say that Fredericks visited him the next morning and agreed to the suggested deal but with a proviso, obviously inserted at the behest of the defense. A typewritten proposal specified that James McNamara would receive any sentence the court saw fit to impose “except capital punishment.” The TI executive’s recitation says that he told Fredericks that unless those words were stricken, “I would not present the matter.” Fredericks phoned later to say that the words “except capital punishment” could be deleted.

Brant subsequently again summoned the DA to his office, the chronicle says, but a deal could not be worked out…but Davis, on Thanksgiving night, went to Frederick’s home and finalized the bargain.

Robinson writes:

“Many years later, on August 7, 1958, Davis made this statement to me: ‘I saved the lives of the McNamara boys. It was my greatest victory. I was the man. I got Otis to agree. Even though the McNamaras had killed all those people, I saved them from hanging. The lawyers gave me the credit.”

![]()

Darrow, in his 1932 autobiography, recounts that a

proposed plea bargain was fashioned during a meeting with the defendants in the

jail. James—who placed the bomb in the alley next to the Times Building

(purportedly set to go off at a time after all employees had gone home)—would

be spared the death penalty and be sentenced to life in prison. James would be

given a term of 10 years for complicity in another union bombing.

complicity in another union bombing.

When Davis approached Fredericks with the proposition, the district attorney “received the suggestion quite favorably,” Darrow writes, “but could not act without consulting with some of the others interested, and that would require word from the Erectors Association of Indianapolis.”

The National Erectors’ Association, which represented steel companies, was a leading proponent of the open shop. After several days, Darrow says, “Mr. Fredericks reported that Mr. [Walter] Drew, [national secretary] of the Erectors Association, was willing to accept the proposition, and it looked favorable so far as the others were concerned.”

Darrow continues:

“We purposely drew out the examination of jurors several days after the negotiations were complete. The procedure was, however, fully agreed upon two or three days before another complication set in.

“When all the parties of the two sides felt certain that the case was to be disposed of immediately, the man who had been placed [by the defense] in charge of the examination of jurors, Bert Franklin, was arrested on the charge that he had handed a prospective juror four thousand dollars on one of the main streets of Los Angeles, as the juror was on his way to the courthouse. Franklin was arrested on the spot and taken to jail. He then protested his innocence and asked us to furnish bail, and so we put up a cash bond, whereupon he was released. In spite of what had happened, the State carried out the agreement to accept a plea of guilty for J. B. McNamara with a life-sentence, and a plea in a separate case by J. J. McNamara with a ten-year sentence. But the judge insisted upon giving [John] J. McNamara a fifteen-year sentence instead of the one that had been agreed to by the State.”

![]()

On Dec. 1, the p.m. newspapers, the Express and the Herald, told in huge-sized banner headlines of the McNamaras’ plea switches that day. Fredericks took the new pleas.

The Herald quotes Fredericks as saying:

“The prosecution has known for more than two weeks that this was going to happen. In fact we have known all along that we ‘had’ the defendants and that there was no way out for them.”

The Express’s report remarks:

“It developed today that the district attorney took the initiative in the arrangement by which the McNamara brothers were to plead guilty to one indictment each, and thereby escape prosecution on the other remaining charges.”

Whether Fredericks “took the initiative” is doubtful. That he did participate in plea discussions seems certain. And yet, the transcript of the Dec. 5 sentencing hearing, published that day in the Herald, shows that Fredericks told the court:

“There has been no dickering or bargaining in this matter.”

That does contradict other accounts—including his own statement issued Dec. 2.

The transcript of the sentencing hearing shows that Fredericks remarked that he would “assume the sentence of imprisonment for life would be considered possibly in some degree a less punishment than the punishment of death”; that James McNamara had provided a “service to the state” by pleading guilty”; and that “some small degree of consideration should be extended to him because of that fact.”

No pact under which James McNamara would be spared the death penalty is reflected in the transcript and, for that matter, there’s no mention of any understanding that John McNamara would be given a 10-year sentence.

Could it be that Darrow, in penning his book, “The Story of My Life,” published when he was 75, and 21 years after the event, simply confused what was proposed with what was agreed upon? He did refer to his client John Joseph McNamara as Joseph J. McNamara. Or was there a promise unkept? If so, no note of it was made at the time by the defense.

![]()

The statement by Fredericks which detailed the plea bargaining appears in the Times’s Sunday, Dec. 3 edition. It mentions that he and Darrow had casually discussed “as far back as last summer” the prospect of James McNamara pleading guilty if the indictment of his brother were scrapped.

Fredericks’s statement continues:

“Again about a month ago, Darrow and I got to talking over the settlement of the case in open court. We got so earnest about it that the court cautioned us about loud talking. The subject was not taken up until later, when Darrow came to my office. I refused to make any compromise, stating that I intended to try both men. He left the offer open in case I wanted to change my mind.

“About ten days ago Darrow and I had a little closer talk. While we went more into details nothing came of it. I now know that influential business men were interested in the proposed arrangement. Friends of mine came to see me to suggest certain things. They did not press me in any way.

“Later a typewritten statement was submitted to me covering the same matter [which might well be assumed to have been the one he presented to Brant]. I knew I ‘had the goods’ on the defendant as the saying is and I didn’t propose to ‘lie down.’ I asked many of my friends if I was making a mistake and they assured me I was right. Later Attorney Davis came to see me about the proposition that has just come to a climax. The lawyers for the defense knew that if ‘J. B.’ were convicted he would hang. Finally as all now know, the lawyers for the defense agreed to my plan, which was to have both men plead guilty as they did in court Friday afternoon.”

![]()

The judge, Walter Bordwell, did something that today would be unthinkable. He issued a public statement concerning the proceedings. It appears in the Dec. 5 issue of the Herald alongside the report of the sentencing.

Bordwell was upset over an account in the Express provided by Lincoln Steffens, a writer who was covering the case for the newspaper while also assisting the defense. Steffens claimed major credit for bringing about the resolution. Bordwell’s statement disputes that claim.

On the one hand, the judge insists that he had no role in the negotiations, and on the other hand, he reveals such intimate knowledge of what transpired as to belie his representation of aloofness from it all.

Here’s part of the judge’s rendition of what happened:

“The district attorney could have had J. B. McNamara’s plea of guilty long ago if he had been willing to dismiss the cases against his brother, but he refused, insisting that the latter was guilty and should suffer punishment. The first proposition from those interested in the defense was that J. B. McNamara should change his plea from not guilty to guilty on condition that he not be sentenced to death, and that his brother should go free.

“The district attorney would not agree. Afterward emissaries from the defense brought to the district attorney the proposition that J. B. McNamara would plead guilty and be sentenced to death, if the court so ordered, provided that his brother should be saved. But the district attorney still would not agree. Those interested in the defense continued to urge his acceptance of the last proposition for ten days or more, and until the bribery developments revealed the desperation of the defense, and paralyzed the effort to save J. J. McNamara by sacrificing his brother.”

Fredericks emerged the victor. One congratulatory telegram was signed “Jim.” It came from Vice President James Sherman. The telegram says:

“Best wishes to yourself and all your associates and congratulations [on] the successful ending of this great trial.”

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company