Tuesday, March 13, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Heated 1910 DA’s Race Gets Even Hotter as Election Day Nears

By ROGER M. GRACE

Twenty-Ninth in a Series

JOHN D. FREDERICKS and THOMAS LEE WOOLWINE were engaged in bitter combat in 1910 for the post of district attorney of Los Angeles County and in the closing days of the battle, the hostility intensified. Fredericks, the incumbent—who had been hammered by his opponent in speeches as well as by E.T. Earl’s Los Angeles Express in print—assumed the offensive.

He had to. Woolwine was gaining support.

The major charge hurled at Fredericks was that he compounded a felony by failing to prosecute a forger of wills of decedent Michael King—instead, civilly representing two daughters of King in contesting those wills, garnering 50 percent of the settlement he negotiated for the clients. Too, he was scored for not prosecuting the former Los Angeles mayor, A.C. Harper, who resigned under threats by Earl that if he didn’t, documentation of his malefactions, such as payoffs from houses of prostitution, would be published. The grand jury did not indict Harper, but suggested that the DA pursue the matter on his own, which Fredericks didn’t. The reason for that, it was theorized, was that this would have displeased Walter Parker, lobbyist for the Southern Pacific Railroad and a power-wielding political boss, who looked with favor on the erstwhile mayor—and who, according to Woolwine—gave Fredericks his orders.

Another charge slung by Woolwine was that three members of the Board of Supervisors in 1908 “would not have dared attempt at private sale to sell the good roads bonds at a loss...of $400,000 to the taxpayers of the county, unless they were reasonably certain of immunity in advance from the district attorney’s office....”

Woolwine also ballyhooed an account by one Guy Eddie who was a prosecuting attorney for the City of Los Angeles at the time a law was passed, subsequently neutered by the California Supreme Court, giving the district attorney authority over city prosecutions of state misdemeanors. Eddie declared in an affidavit that when this happened, Fredericks took from him the prostitution cases he was pursuing—including one which involved a county official who allegedly leased a house knowing it would be used for prostitution purposes—and none of the cases came to trial.

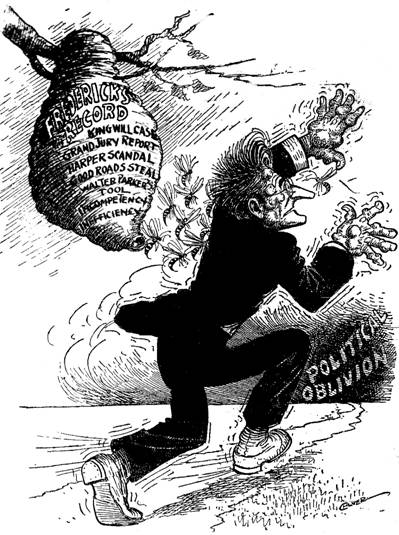

Here’s an editorial cartoon published in the Express on Nov. 5, with the heading: “ON THE RUN”:

![]()

Faced with all that, Fredericks brought more unfavorable attention upon himself by, to employ modern jargon, “losing his cool” at a meeting in Glendora. As the Express’s edition of Oct. 28 recounts the episode of the previous evening:

“One of [Fredericks’s] questioners, Frederick C. Schiffman, was arrested by Fredericks for lese majesty. Specifically his crime was that he asked a question which humiliated the speaker. Fredericks replied by calling Schiffman a personally offensive name and later placed him under arrest. That he did not carry out his threat to take him to Los Angeles and lock him in the county jail for the slight was because he lacked the courage to carry through his bluff in the face of an angry crowd.

“It was the supreme blunder of a campaign of stupidity. The man he arrested is a millionaire rancher, who is unanimously conceded to be the most popular man in Glendora.”

The article says that Schiffman called out a question as to why, if Woolwine’s allegations were false, he did not prosecute his antagonist for criminal libel; Fredericks explained that the statements, having been made orally, were slander, not libel; Schiffman reminded the DA that they were uttered orally for the purpose of being published in a newspaper; Fredericks said he did not know that to be a fact and, when the questioner persisted, cut him off by thundering:

“Aw, you run away, Fatty.”

Schiffman was escorted out but, as Fredericks spoke, could be heard from an anteroom; Fredericks asked from the podium that the marshal be summoned to arrest Schiffman for creating a public disturbance; after the meeting, they quarreled, with Fredericks wavering between making a personal arrest of Schiffman and having a marshal come to fetch the supposed lawbreaker in the morning.

The morning Herald’s editorial on the incident, appearing on Oct. 29, says:

“BECAUSE Frederick C. Schiffman, one of the prominent citizens of Glendora, asked a perfectly proper question of Captain John D. Fredericks, the district attorney threatens him with arrest and all but carries out his threat. Considered as a matter of tactics the candidate made an egregious mistake in losing his temper. He displayed a side of his character that nobody had yet called attention to—a side that ought to be considered in the choice of a man to entrust with great power.”

While the term “heckle” is in common parlance in the United States today, it apparently wasn’t in 1910. The editorial says:

“The case is of more than superficial importance, for it serves as a reminder of a very healthy English custom, called ‘heckling,’ which might well be adopted in this country. Every candidate for the suffrage in England expects to be heckled: that is, to be asked all sorts and manner of questions, wise or foolish, germane or otherwise, from the floor and to answer them in good temper. If he should lose his temper and act boorish he would be hooted from the platform.

“….No man with a good cause and good record would fear heckling, but it is conceivable that the other kind might.”

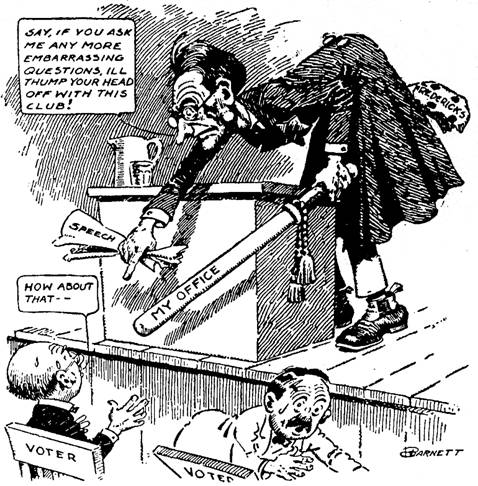

This cartoon accompanied the editorial:

The Examiner, by contrast, decried the heckling, saying in an Oct. 31 editorial:

“A candidate may with propriety be asked by auditors questions couched in decent language, and it is his duty—at least, he should regard it as his privilege—to reply, presupposing that the inquiry is made in good faith. But when organized efforts to turn a meeting into a ‘rough-house’ are made and the meeting becomes the scene of vilification and abuse with the target the candidate, the purpose of the meeting is defeated. Such a situation is neither democratic nor American.”

![]()

What did the pro-Fredericks Los Angeles Times have to say about the matter? Nothing.

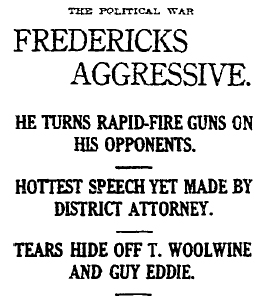

Fredericks’s conduct reflected unfavorably on him, so it wasn’t reported. The newspaper’s Oct. 28 account of the meeting in Glendora bears the headlines below.

The article, within the first paragraph, seeks to dispel the impression that Fredericks was on the defensive:

“He said at the outset that he was not there to explain, but to show the animus and unjustifiable character of the attacks that had been made against him and to throw some light upon the record of the man who aspires to be District Attorney.”

The Times quotes Fredericks as lambasting Earl for thwarting his investigation of graft in the Harper Administration, for gaining his wealth through shoddy business practices, for having “slung his lash over the shoulders” of the new mayor, procuring his endorsement of Woolwine.

He denounced Woolwine for claiming to have been in the United States District Attorney’s Office for four years when he was only there a year, and as a stenographer. The DA belittled his challenger for representing that as city prosecutor, he closed down “bucketshops” (brokerage firms engaging in fraudulent practices) when he only raided one of them, and on that occasion was accompanied by press photographers, and arrested supposed customers who were actually DA’s investigators who had been amassing evidence over a one-week period, frustrating their efforts.

The article relates that the speaker declared:

“Woolwine’s mud battery is turned into his own camp when he attempts to use an affidavit from the immaculate Guy Eddie to the effect that I ordered him to dismiss a certain case, when it appears that Mr. [Edward J.] Fleming, now a member of the same camp, himself states that he dismissed the case without consulting or notifying me.”

![]()

The District Attorney’s Office website, in its section on past DAs, says of Woolwine, with seeming approval:

“He even raided the prestigious California Club once in his zeal to control illegal liquor, gambling, prostitution and, most importantly, public corruption.”

That raid was conducted in 1908 when Woolwine was Los Angeles city prosecutor. He accompanied police when they entered the premises, seized huge numbers of bottles of liquor, and arrested the directors, the manager of the bar, and the bartender. They were charged with selling liquor without a license in contravention of an ordinance. Prior to the raid, the directors had assured Woolwine of their cooperation in setting up a test case, disclaiming applicability of the ordinance to social establishments—a position which the California Supreme Court the following year validated.

Woolwine’s action came in for scalding criticism late in the 1910 contest. Fredericks brought it up during a talk in Pasadena on Nov. 2. Picking up on it, the Examiner on Nov. 6 re-ran two 1908 editorials from the newspaper, which had then been under different ownership, positioning the editorials at the top of Page One. “Raiding in the style of Carrie Nation is the expedient usually of a person who doesn’t know the law or who seeks cheap notoriety,” one of the editorials says. The other calls the maneuver a “stupid blunder” and contends: There is no MAJESTY in the law that notifies reporters of all the newspapers and photographers that the City Prosecutor is about to raid the California Club so that there may be printed moving pictures of Woolwine and his assistants in action.”

Below the repeated editorials on that front page appears a new one, expressing this view:

“[T]he real question is not whether Fredericks is an ideal District Attorney, but whether Woolwine has the poise, the temperament, the judgment that the prosecuting officer of this county should have. Would Mr. Woolwine make a sensation-seeking, erratic, unbalanced and therefore unsafe District Attorney? Is his love of notoriety and the camera, his fondness for noise and acclaim, his extreme and extravagant manner and method of statement, to be regarded as likely to injure or limit his presumptive usefulness as the people’s lawyer.

“These are questions voters must ask themselves and answer.”

The answer was provided by voters on Nov. 8. Fredericks—though surely not an “ideal” DA—was returned to office. Concerns that Woolwine would be “unsafe” no doubt proved a preponderating factor in the electorate’s decision.

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company