Tuesday, March 6, 2007

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Taxpayers Caused to Wonder if DA, Deputies Were Cheating Them

By ROGER M. GRACE

Twenty-Eighth in a Series

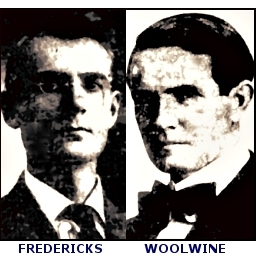

Allegations by challenger THOMAS LEE WOOLWINE in the 1910 contest for the post of Los Angeles County district attorney caused some taxpayers to wonder whether incumbent JOHN D. FREDERICKS and his deputies were, in fact, cheating on them by devoting attention to private financial pursuits during office hours.

Woolwine, a Democrat, alleged at the outset of the campaign, on Sept. 30, that the Republican Fredericks had compounded a felony by failing to prosecute the forger of codicils to a genuine will of one Michael King, as well as an entirely bogus will attributed to King. The non-prosecution, Woolwine charged, was in return for a settlement under which Fredericks’s private clients, who were contesting the wills, were given a share of King’s estate, with Fredericks reaping a 50 percent contingency fee.

Voters who wanted to believe the charge did, though sufficient facts to show criminality on Fredericks’s part simply were not produced. In any event, some of the public was no doubt caused to wonder why Fredericks, who was being paid a salary for the fulltime post of district attorney, was practicing law on the side.

And even if Fredericks did not actually use his position to benefit civil clients, didn’t that prospect exist with respect to any DA who had a shingle hanging out?

![]()

The fact is that Fredericks, the county’s 26th DA, was doing nothing unconventional.

A letter used by Fredericks in his campaign from Walter J. Trask, president of the Los Angeles Bar Assn., says:

“Every previous District Attorney, including the late Honorable Stephen M. White, has while in office, taken part in civil cases, irrespective of the fact that proof justifying a criminal accusation might be therein finally established.”

Fredericks also cited a letter to him from George J. Denis, a former “U.S. district attorney” (now known as “U.S. attorney”). It declares:

“It is silly to talk about a District Attorney not being permitted to take private practice. Without exception in the United States such officials may under the law, and do, take private cases, providing that they attend to their official duties efficiently, as without doubt you have done.”

Among others writing letters attesting to the ethical nature of Fredericks’s conduct were former District Attorney Henry C. Dillon, a Democrat, and criminal defense attorney Earl Rogers.

In the early days of the District Attorney’s Office—from 1850 to decades after that—the DA personally conducted all prosecutions, having no deputies. Still, it was not a fulltime job, and the pay reflected that. But now the district attorney did have deputies, the assumption and reality being that the job was too big for one man to handle. So, was it still justifiable for a district attorney to divert attention from his official duties by making court appearances during office hours on behalf of private clients and consulting with them in his office in a public building?

![]()

Woolwine apparently hit a responsive chord in assailing Fredericks’s activities as a private practitioner. He was impelled to look into the extent of the law practice of Fredericks’s deputies.

Woolwine made a pledge on Oct. 14 at a meeting in Watts that if he were elected, he would not to undertake private civil cases or allow his deputies to do so. The Los Angeles Express’s edition the next night contains this quote, the parenthetical insertions being those of the Express:

“When the people pay public officers for their time, such time is the property of the people and to squander it and use it for private gain to the detriment of the public welfare is nothing more or less than the embezzlement of such time.

“The district attorney (Fredericks) and

his deputies, during that time (four years) appeared as attorneys  for private

parties in 395 civil cases. . .There has been consumed in the 395 cases, not

less than 1185 days of the people’s time for which Mr. Fredericks and these

deputies were paid and for which they rendered no service.”

for private

parties in 395 civil cases. . .There has been consumed in the 395 cases, not

less than 1185 days of the people’s time for which Mr. Fredericks and these

deputies were paid and for which they rendered no service.”

Fredericks’s rejoinder came the following night at a meeting in downtown Los Angeles, arranged by the Republican County Central Committee to give the DA a chance to tell his side of the story on the various issues that had been raised. In light of the gravity of Woolwine’s charges, there was agitation from some quarters for the GOP to repudiate the candidacy of Fredericks, chosen by voters under the new Direct Primary Law. This resembled the scenario in 1952, on a national level, when there were calls for Richard M. Nixon to be yanked as the party’s candidate for vice president.

In his analogue of Nixon’s televised “Checkers” address, Fredericks explained that the civil cases he and his deputies had undertaken were primarily minor ones “growing out of official works,” handled at “odd hours” and on a pro bono basis.

He recalled Woolwine having himself represented private clients in civil cases while a prosecutor, and maintained that his opponent, in handling a probate case for a fee, used a city letterhead, and utilized services of a city stenographer and a city typist.

![]()

Prior to Fredericks’s talk, the man who presided over the meeting spoke out on the incumbent’s behalf. He was Wheaton Gray, the first presiding justice of the Court of Appeal for this district, serving from April 1905 to January of 1907. He previously sat as a Tulare Superior Court judge, then as a Supreme Court commissioner.

I mentioned Gray in the last column. As reported by the Los Angeles Times, Gray physically blocked E.T. Earl, owner of the Express, from seizing the podium at that Oct. 15 gathering, telling the Woolwine ally: “I’ll beat your damned head off if you attempt to come up on this platform.”

The Express’s Oct. 17 report of that meeting, which identifies Gray only by his surname and as “a pompous old man,” recounts:

“He declared that Woolwine was working up a silly storm in pointing out the fact that the district attorney’s office had devoted…[much time] to the gleaning of side money by prosecuting private civil cases representing private clients in civil litigation at the expense of the people.”

The article continues:

Fredericks had the right to take salary for six days in the week and devote as much of the time to private practice, declared the ponderous speaker….

“Now Woolwine promises, if he is elected, that neither he nor his deputies will accept civil cases—,” said Gray, but he could get no further for several minutes. The audience burst into a storm of applause, which finally merged into cheers. The speaker grew black in the face and shook with suppressed indignation as the crowd cried again and again:

“Hurrah for Tommy Woolwine! Woolwine! Woolwine!” and continuing deafening stamping and clapping of hands.

Nonplused, but wrathy, Gray endeavored to continue.

“Who will you get to take this office at the limited salary and without the privilege of adding to his income through civil cases?” he demanded.

“Woolwine!” gleefully rejoined the audience and the laughter interrupted proceedings again.

“And he’s the only one fool enough to take it,” shrieked the ponderous one, trembling with anger. “You can get men the caliber of Woolwine—”

“Rah for Woolwine! Give us more like him,” was the answering cry and wave after wave of applause followed.

None of this explosion of support for Woolwine at the address by Fredericks, as described in the Express, is reflected in the pieces appearing in the Times or the Examiner, newspapers supporting Fredericks.

![]()

Woolwine on Oct. 18 responded to the charge that he used city resources in connection with a probate case by saying that he associated-in a law firm in that case for the very reason that the demands of his official duties precluded him from handling the case himself.

An editorial in the Express on that date scoffs:

“Mr. Fredericks has not satisfactorily explained why he lets his many deputies take the county’s time for private law practice, except to say it is for ‘charity’ cases. Who believes that? The King will case (which set the example) is certainly not a charity case.”

The Times’s Nov. 3 editorial contains this counter-scoffing:

“Alone, among all the District Attorneys of the State or of the United States, Tommy [Woolwine] would have virtuously refused to transact any civil business. Let the client on bended knees beg Tommy to accept a fee, and he would have begged in vain, and the deputy who ventured to write a note to his girl on the office stationery would have been told: ‘Sir, the paper and the ink and the time you are using belong to the State of California. I will not allow such larcenous malfeasance in this office. Depart, ye cursed, into everlasting fire,’ or words to that effect.”

![]()

Fredericks had done nothing that was criminal or uncustomary. Yet, it didn’t smell right.

I can find nothing in the discussions of the campaigns at the time suggesting that even if it was permissible for Fredericks to handle a probate case while district attorney, once an allegation of “forgery” arose in the case, he should have withdrawn. But I also see no reference in cases it that time of a necessity to avoid even the “appearance of impropriety.”

There were, of course, ethical standards for lawyers then, and statutory restrictions.

In 1882, the California Supreme Court imposed a three-month suspension on a lawyer who, as Lassen County district attorney, had drawn up an indictment against a man in 1874 and, as a private lawyer in 1881, moved to set aside that very indictment. The high court said that aside from the fact that a statute rendered it a misdemeanor for a former prosecutor to represent someone he had prosecuted, “there can be no doubt that his conduct was reprehensible” in light of the inherent conflict.

Citing the proposition that “an attorney may be stricken from the rolls for acting in an action or suit on both sides,” the state Supreme Court in 1886 suspended a lawyer for six months because he had accepted a $100 fee from the respondent in two appeals taken by the City/County of San Francisco. The attorney had brought those appeals while serving as city attorney. His term ended. He took the fee in exchange for a promise not to provide continued representation to the city/county as special counsel.

The precept had developed that a lawyer could not switch sides with respect to any given piece of litigation. Presumably, if the prospect had emerged of a need to prosecute the persons Fredericks was representing as civil clients, a problem would have been perceived. But the potential prosecution was not with respect to his own clients but, rather, one or more of the opposing parties.

There was apparently no cognizable breach of ethics in those days in Fredericks representing civil clients who were asserting that a forgery had been committed in light of an apparent lack of proof beyond a reasonable doubt that a crime had been committed and, if there was a crime, who committed it.

![]()

Of course, there was a question as to whether such proofs might have been uncovered had the DA not been in a position of profiting from a contingency fee if they weren’t.

Even if Fredericks did not actually use his position to benefit civil clients, didn’t the prospect of that occurring exist with respect to any DA who had a shingle hanging out?

Questions of that sort apparently lingered in the minds of the populace of the county even after the 1910 election concluded. A county charter, approved by voters on Nov. 5, 1912, and ratified by the Legislature, went into effect June 2, 1913. It expressly barred law practice by the district attorney, or by holders of the posts of county counsel and public defender, or by their deputies. It provided, as it does now:

“The District Attorney, Public Defender, County Counsel, and their deputies, shall not engage in any private law practice, and they shall devote all their time and attention during business hours, to the duties of their respective offices.”

On March 5, 1913, two months before the charter was to go into effect, Fredericks’s chief deputy, Byron C. Hanna, resigned rather than unwind his private practice. The Times’s edition the next morning quotes Fredericks as saying:

“This shows again that we must either pay better or allow the deputies to engage in private practice. Hanna never neglected his duties here for an instant, he conducted his private practice by night work.”

Copyright 2007, Metropolitan News Company