Metropolitan News-Enterprise

Thursday,

March 9, 2006

Page

15

REMINISCING (Column)

Judge Bars Use of Word ‘Cola’ in Names of Coca-Cola Rivals

By

ROGER M. GRACE

The

Coca-Cola Company had an ambition. It wanted to sell the only drink bearing a

name that included the word “cola.”

As

mentioned here last week, a Fourth U.S.

Circuit Court of Appeals decision in 1921 expressly took no position as to

whether the Coca-Cola Company possessed such a right. The company set about to

establish that it did.

It

brought suit in the U.S. District Court in Maryland

against three corporations and 11 individuals for unfair competition. By the

time a decision was reached, one of the corporations had gone out of business.

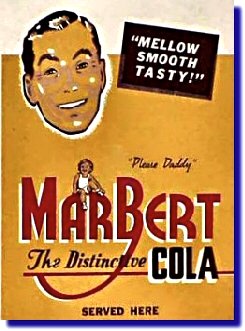

Accepting the Coca-Cola Company’s contentions, Judge William C. Coleman on Feb.

27, 1940 enjoined the use of the brand names Dixi-Cola, Marbert-Cola, and

MarBert The Distinctive Cola.

It

brought suit in the U.S. District Court in Maryland

against three corporations and 11 individuals for unfair competition. By the

time a decision was reached, one of the corporations had gone out of business.

Accepting the Coca-Cola Company’s contentions, Judge William C. Coleman on Feb.

27, 1940 enjoined the use of the brand names Dixi-Cola, Marbert-Cola, and

MarBert The Distinctive Cola.

Coleman

noted that various courts had likewise enjoined use of trade names containing

the word “cola” notwithstanding a lack of confusion of those names with

“Coca-Cola.” He pointed to the name “Champion-Cola,” nixed by another judge of

the District Court in Maryland

14 years earlier in an unreported decision.

“Of

all reported, contested cases, our attention has been called to only one in

which the alleged infringing name has not been enjoined” at the behest of the

Coca-Cola Company, Coleman wrote. He cited, and quickly dismissed, that one

decision, rendered in 1930 by the Sixth U.S. Court of Appeals. It upheld a

decision denying an injunction against use of the name “Roxa Cola.”

Coleman

said:

“[T]this

Court believes that the plaintiff is entitled to the relief asked for,

namely...an injunction preventing the defendants from using, as part of the

name of their products, the word ‘Cola’, regardless of whether the syllable

placed in front of the word ‘cola‘ is like or unlike the syllable

‘Coca’—whether it looks like it, or when pronounced, sounds like it. This does

not mean that the defendants cannot use the word ‘Cola’ or the word ‘Coca’, or

both, separately, on their labels otherwise than as part of the name itself….”

The

Coca-Cola Company complained of instances where customers asked for its product

at soda fountains and bars but were instread served glasses of one of the

defendants’ colas, and alleged that the passing off was encouraged by the

defendants, Coleman found that “plaintiff is entitled to have the defendants

enjoined from employing for their products the same color as that of Coca-Cola

if defendants distribute, or permit their products to be distributed, or sold

to the consumer other than in bottles.”

Sidenotes:

•The opinion revealed

that over the past several years, the Coca-Cola Company had been bringing

infringement actions at the rate of one a week.

•Coleman in 1930

unsuccessfully opposed the appointment of a man as U.S.

attorney for Maryland

because he was Jewish. After all, the “job called for a person of some social

standing,” Coleman wrote to the U.S.

attorney general. This was during Prohibition and, in light of the number of

Jewish bootleggers in Baltimore,

Coleman suggested it was “unwise to appoint a Jew.”

•The federal trial court

decision in the Roxa Cola case alluded to advertising songs put out by the

manufacturer of the beverage implying that it (like Coca-Cola of days gone by)

provided the effects of cocaine. One ditty from 1916 or 1917 went like this:

“Ashes to ashes, dust to dust [¶] If cocaine don’t get you, Roxa Kola must.”

The chorus of an advertising song circulated in 1913 included these words: “Oh,

its Roxa Kola dope, [¶] It gives a body new hope [¶] Things don’t seem the

same, [¶] When a glass you’ve drained.”

Coleman was reversed, at least to

the extent that he found the word “cola” to be the protectible property of the

Coca-Cola Company. The Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 1941 held that

the word “cola” has “become a generic term, used in common by manufacturers as

part of the trade-names for their products.”

Ironically,

the circuit judge who authored the opinion, Morris Ames Soper,

had been the author of the 1926 District Court opinion, relied upon by Coleman,

which found “Champion-Cola” to infringe on “Coca-Cola.”

Soper’s

opinion backed Coleman’s order that brown coloring, derived from caramel, not

be used by Dixi or Marbert, except in bottles sold to consumers.

Copyright 2006, Metropolitan News CompanyMetNews Main Page Reminiscing

Columns

It

brought suit in the U.S. District Court in Maryland

against three corporations and 11 individuals for unfair competition. By the

time a decision was reached, one of the corporations had gone out of business.

Accepting the Coca-Cola Company’s contentions, Judge William C. Coleman on Feb.

27, 1940 enjoined the use of the brand names Dixi-Cola, Marbert-Cola, and

MarBert The Distinctive Cola.

It

brought suit in the U.S. District Court in Maryland

against three corporations and 11 individuals for unfair competition. By the

time a decision was reached, one of the corporations had gone out of business.

Accepting the Coca-Cola Company’s contentions, Judge William C. Coleman on Feb.

27, 1940 enjoined the use of the brand names Dixi-Cola, Marbert-Cola, and

MarBert The Distinctive Cola.