Thursday, February 2, 2006

Special Section

PERSONS OF

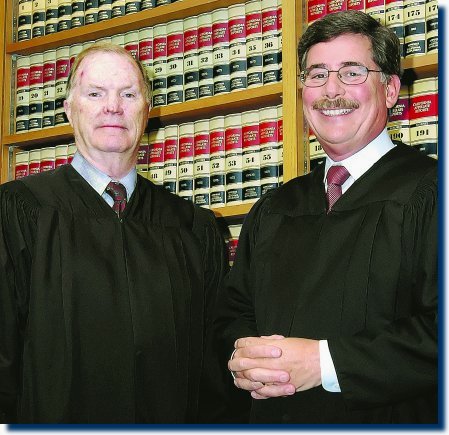

THE YEAR, 2005: Los Angeles Superior Court Presiding Judge William MacLauglin

and Assistant Presiding Judge J. Stephen Czuleger

Judges William MacLaughlin and J. Stephen Czuleger

MacLaughlin, Czuleger Bring Stability to Court Leadership

Presiding Judge and Assistant Differ in Style and Background but Not in Views on Superior Court Direction

By DAVID WATSON, Staff Writer

Compare and contrast Bill MacLaughlin and Steve Czuleger?

If it were an essay assignment, the contrast part would be easy.

Los Angeles Superior Court Presiding Judge William A. MacLaughlin, who will turn 71 this year, looks and sounds a lot like the weathered cowboy that, when he gets any time for it, he still is.

A native Midwesterner and graduate of Yale Law School who came to California in the early 1960s and fell in love with horses and the West, MacLaughlin, whose father and older brother were also lawyers, has a way of hesitating before he answers a question that suggests he is weighing alternatives. Sometimes the hesitation lasts long enough to make his interrogator start doubting whether it was such a good idea to ask that particular question.

It’s a manner that might remind some of the laconic Western characters played on the screen during MacLaughlin’s youth by another Iowa native, Marion Morrison — better known as John Wayne.

Assistant Presiding Judge J. Steven Czuleger, who has served since the beginning of last year with MacLaughlin and will, barring an unprecedented break with court tradition, take over for him at the beginning of next, is none of the above. Nearly 16 years MacLaughlin’s junior, though he has served on the bench for four years longer, Czuleger is a native Californian, born into a family of shopkeepers, who was halfway through college in the early 1970s before it suddenly dawned on him that the grades he was getting weren’t going to get him into law school.

He got serious, got into Loyola Law School, and became a federal prosecutor.

Shorter and stockier than MacLaughlin, Czuleger differs from the presiding judge as much in manner as in physique. He seems to anticipate questions, answering them almost before they are asked and often asking the follow-up question himself, as bright people who think best by talking sometimes will.

If MacLaughlin is the Midwesterner who found a home in the West, perhaps Czuleger typifies the restless Californian ever in search of new places and experiences. It’s no surprise to learn that his passion is travel, and that he, his wife, and their two college-student sons have just returned from a cruise that took them through the Panama Canal.

While the contrasts between these two men, one born just before and the other soon after a great world war, are easy to draw, finding the common ground that ties them together requires probing a little more deeply into the institution they have been chosen by their colleagues to lead.

The Los Angeles Superior Court is a mammoth entity, and one in the throes of a challenging transition.

Less than a decade ago, it was only one — though the biggest and most important — of more than two dozen independent courts in Los Angeles County, and its funding was in the hands of the county’s Board of Supervisors.

In 2000 it absorbed the municipal courts and the state has taken over its funding. More recently, the administrative apparatus of the state’s court system — the Administrative Office of the Courts, the Judicial Council, and the council’s ex officio leader, Chief Justice Ronald M. George — has begun to exert an ever-increasing influence over how the states 58 trial courts are funded and operated.

That influence is likely to increase if proposals, initiated by George and the council, for a far-reaching revision of Article VI of the state Constitution, which deals with the judicial branch of government, come to fruition. It is a trend that poses unique challenges for the Los Angeles Superior Court, which, with more than a third of the state’s nearly 1,500 trial court judges, is far and away the biggest member of the branch.

Centralization Praised

Both MacLaughlin and Czuleger readily admit that the trend toward centralization is one with which the giant court, so used to making decisions for itself, is institutionally uncomfortable. But both also see it as a trend that could benefit the judicial branch as a whole, and the Los Angeles Superior Court along with it.

“I think that there has been, over the last decade in particular, a considerable centralization in terms of authority within the judicial branch,” the presiding judge concedes. “I think that that is neither good nor bad....[T]here needs to be balance, and...in many areas central authority is necessary for success of judicial branch. But...there are many areas in which local autonomy are also essential. And I think the challenge, and this is a challenge for our court and for every other court and also for the AOC, is trying to find the proper balance.”

He adds:

“I know that we never achieve perfection. So I am not looking for the perfect balance. But what I am looking for, as I believe they are too, is...a place where central authority is being exercised in areas where it is beneficial and for the greatest good, and that local authority is being exercised in the areas where it provides the greatest good....There will sometimes be some conflicts, that is we’re going to have some different points of view within the judicial branch as to where that balance point ought to be. And when we have a difference of opinion, then I think both sides need to go to work on resolving those differences. And I think this is a big challenge but I think it’s doable. I know that’s what I’m working for and I believe that’s exactly what the AOC is working for.”

Czuleger points out that the Article VI proposals, as finally approved by the Judicial Council late last year, differed greatly from the form in which they were first floated at a Sacramento meeting in February of 2005. Many of the changes, he argues, represented input from Los Angeles and other superior courts.

“When state court trial funding went in, we started the process of making it one branch of government,” the assistant presiding judge says, adding:

“We’re still in that process....And in that there’s give and take....And this is a great discussion. I’m very excited by the discussion....I think if there is discussion, if it is open, if people really speak their minds, out of that comes an awful lot of good things in governance.”

Czuleger continues:

“What I’m most interested in is that you have buy-in. Are you going to make all the judges in the State of California happy? No. You can never get all the judges to agree on anything. But do you have buy-in? Do you have confidence? And I think it’s a matter of gaining confidence. That the AOC has confidence that the local trial courts are moving generally in the same direction, and that the local trial courts have confidence that the AOC has the best interests of the branch at heart.”

Czuleger says the vetting process for the proposed Article VI changes produced that kind of buy-in.

“That’s something that’s not that unusual,” he comments, suggesting that bringing about change in corporate cultures in the business world requires a similar process.

Article VI

Both jurists are quick to point out that the Article VI reforms, which would stabilize funding for the judicial branch and more exactly define the Judicial Council’s role in administering the state courts, still face many hurdles before they can become a part of the Constitution. The council is seeking legislative support for the proposals, which would then have to go before the voters.

If lawmakers fail to support the plan, or change it too much, George and others have suggested an initiative campaign might be considered. Either way, an effort to build public support for the changes will be required, and a vote will test whether the electorate has the same sense that the court system is central to public welfare that it demonstrated it had about the school system when it passed Proposition 98 in 1988.

Czuleger says he thinks the voters do.

“Virtually everyone is touched in some fashion by the court system,” he comments. “....I think that’s one of the directions that the chief justice very effectively is taking us and rightfully so is building confidence, letting people know that the courts are here for you, that we do take into account the needs of the people.”

The Los Angeles court, the assistant presiding judge says, has played a part in building that confidence, for example by limiting jury duty in most cases to a single day of attendance for those not actually selected for a jury.

“Those jurors that actually sit on a jury come away with a very good sense about themselves and about the system,” Czuleger declares. While those who do not are more likely to have negative feelings, those are at least partly addressed by limiting the amount of time required, he explains.

MacLaughlin says the funding stability promised by the reform proposals would be a major boon to the court.

“In good times or bad times financially, our business stays the same,” the presiding judge points out. “We don’t have business cycles....Even if times are bad, we still have to do the things we do. For that reason the stability is necessary and the predictability is necessary, because we can’t change things in midstream. We cannot suddenly stop handling a certain kind of business.”

Neither MacLaughlin nor Czuleger envisioned himself in anything like his current role early in life.

Lawyer’s Son

MacLaughlin grew up in Davenport, Iowa, and though his father was a lawyer and practiced in the same town, he was not a part of his sons’ lives during most of their childhood. MacLaughlin, his mother, and his older brother struggled financially.

“I started working at my first paying job when I was eight and I’ve been employed every day of my life since then,” the presiding judge recalls.

|

|

|

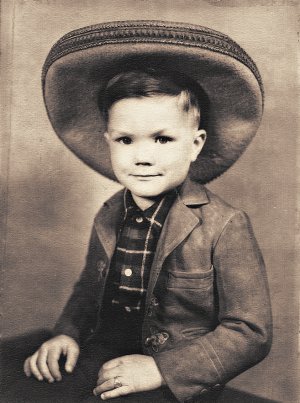

MacLaughlin in a childhood portrait taken in Davenport, Iowa around 1938. |

MacLaughlin and his older brother were befriended by a local businessman who was a Yale graduate and on the lookout for high school students with Ivy League potential. Though his older brother went to Yale and became an attorney, MacLaughlin did not as a youth expect to do the same.

Instead, encouraged by his high school public speaking coach, MacLaughlin says, and despite having been accepted by Yale as a scholarship student, he planned to enroll at Northwestern University, which had also offered him financial support.

The coach “had become a mentor and a sort of a father figure in many ways,” MacLaughlin recounts, and had helped to arrange both his admission and the scholarship at Northwestern. Partly out of loyalty, the jurist remembers, he probably would have stayed in the Midwest had the coach not “sat me down and told me that he thought I’d be making a big mistake if I passed up” the opportunity presented by the Eastern school.

“And I think that was without question the motivating reason why I went to Yale,” MacLaughlin says. “Because I knew how much he wanted me to go to Northwestern, and with him telling me I should go to Yale I thought I should do it. I had great regard for him and I knew I was probably breaking his heart but I knew he was doing what he thought was best for me.”

Law school, too, was a sort of an afterthought, as the presiding judge tells it.

Though he had taken the LSAT, MacLaughlin had not applied to law schools, and was interviewing with international business firms. But on a train ride back to New Haven from a New York interview, he says, “I realized I couldn’t see myself doing what they were doing 20 years down the road.”

Fortunately, Yale’s dean of undergraduates, in whose office MacLaughlin had a part-time job, asked him about his job search. Told of his misgivings, the dean walked him through an application to Yale’s law school, even though the application period had technically already closed.

“In essence he got them to agree to accept a late application,” the jurist remembers. “It was kind of a rush job. Everything in those days was less formulistic and less formal than they are now.”

Move to California

Almost equally fortuitous was his move to California, MacLaughlin explains. He was interviewing with New York law firms when a senior partner, who turned out to have attended law school at the University of Iowa with MacLaughlin’s father, invited him to dinner and suggested the move.

“I had never been to California and had never even really considered coming to California,” the presiding judge says.

“In the course of the dinner...he told me that if he was a young person getting out of law school at that time that he would go to California. He thought the future was in California.”

MacLaughlin interviewed on campus with both Gibson Dunn and O’Melveny & Myers, and took a job in Los Angeles with the former firm.

His period as an associate was soon interrupted by military service, and by the time that was over, the presiding judge says, he was ready to move on to something else. Work at the large firm was not providing the prospect of appearing in court, and his military service had left him a step behind other recent hires, he notes.

“[T]he other attorneys I had started with, their careers were going on, my term there had been interrupted, so I was really having to in effect start all over again,” he recalls.

MacLaughlin litigated in Los Angeles for the next three decades, sometimes alone, sometimes with a changing cast of partners or contract associates. His work included construction defect and contractual issues, and environmental, employment and personal injury litigation on behalf of both plaintiffs and defendants.

He also developed his second career — cattle rancher.

“I grew up loving horses, without being able to tell you why,” MacLaughlin recalls. “One of my many jobs when I was in junior high school and high school was in a stable in Davenport where I would clean stalls and saddle horses in return for getting to ride for nothing.”

First Horse

He bought his first horse in mid-1960s, boarding it at Griffith Park. “That was kind of like a fulfillment I guess of a dream,” he says, “because we had certainly never been in a position to own a horse before then.” Then, in the early 1970s, he and a partner purchased a ranch in western Montana.

The partner was a horseman he had represented in a suit against a former employer, MacLaughlin explains. The ranch, at first small, eventually grew to 20,000 acres, about half of it leased grazing land.

“It was a working cattle ranch, what we call a cow-calf operation,” the presiding judge notes. They bred calves and sold them to “feeder operations,” which raised them for meat.

Typically they had about 1,500 cows, each with a calf from calving season in the early spring to fall, when the calves would be sold. The ranch employed two full-time cowboys, with MacLaughlin’s partner there full-time and MacLaughlin helping out whenever he could be away from his law practice.

It was not, he says, a gold mine.

“Pretty much over the years it was a break-even proposition,” the jurist concedes.

But it did allow him to work with horses even more, and also led to the development of his interest in competitive roping. A cow on the ranch got herself in a ditch, MacLaughlin brings to mind, and his partner had to lasso her to drag her out.

“I could rope but I wasn’t particularly good at it,” he recalls. “At the time I was thinking, you know, I ought to be a little better with a rope than I am.”

He contacted professional roper who had a ranch near Malibu and talked him into teaching him. Soon he was competing in roping events, in which two horsemen working in tandem pursue, rope and tie down a calf or young steer.

He continues to compete when his schedule allows.

|

|

|

MacLaughlin in cap, ropes a steer during competition in Riverside in the mid-1990s. |

MacLaughlin gave up the Montana property in 1988, but in the late 1970s he acquired a ranch in northwest Los Angeles County where he and his second wife have raised horses for the past 28 years.

MacLaughlin says he “never aspired” to be a judge, and attributes his presence on the bench to the influence of Los Angeles lawyer Robert Tourtelot of Tourtelot & Butler, then an advisor to Gov. Pete Wilson helping in the selection of Southern California judicial candidates.

Tourtelot, MacLaughlin explains, had contacted him a couple of times about the idea, and MacLaughlin had demurred. But MacLaughlin was also feeling as though he was ready for a change, and had been looking into a variety of business opportunities outside the practice of law, some involving horses and others not.

“You’re going to begin seeing a pattern here,” MacLaughlin says with a sly grin. “As I began looking at these alternatives more closely I realized that I wasn’t able to see myself doing it in the long term....I realized that both the interest in horses and any other possible business pursuit weren’t going to be sufficiently engaging to me on a full-time basis.”

He adds:

“It happened that Bob called again during that evaluation period. Even then I wasn’t too interested, to tell you the truth, mainly because I hate forms, and he sent over the application that you had to fill out. I took one look at that and said, ah, I’m not going to do that.”

But Turtelot, MacLaughlin says, was “very persistent,” eventually convincing MacLaughlin that MacLaughlin’s longtime secretary, Dorothy French, could manage most of the paperwork burden for him.

“She was without question the best person at her job I’ve ever known — I mean at any job,” the presiding judge observes.

Once the paperwork was done, the appointment to the Los Angeles Superior Court soon followed in 1992.

By then, Czuleger had already been on the court for two years.

Though his path to the bench was shorter than MacLaughlin’s, Czuleger, like MacLaughlin, did not choose law as a career early.

South Bay Upbringing

Born in Long Beach — he explains he has always used his middle name, Steven, because his first name, like his father’s, is John, and his parents decided he was “not going to raised as little John” — Czuleger grew up in Redondo Beach, where his grandfather had started hardware store in 1930s. His grandfather, who came to California from South Dakota by way of Pennsylvania, later opened an appliance store next door, which Czuleger’s father operated.

The only male child of four siblings — one sister is a clerk with the court — Czuleger says he had only vague career plans until his sophomore year at the University of Santa Clara. When a counselor asked him about goals, Czuleger recalls, he suggested teaching might be interesting.

Informed that there were no jobs in teaching, Czuleger says, he ventured that law might be a possibility, only to be told that with his grades he had a “snowball’s chance in hell” of getting into law school.

By the end of that school year he had improved his mediocre grades, finishing school as a political science major and heading off to Loyola Law School.

Having to work, he attended law school mostly at night, and his path in the legal profession was determined, he explains, when he got a day job working as a clerk for U.S. District Judge David Williams of the Central District of California, the first black federal judge west of the Mississippi and one of the first black judges in California.

The job was described in the federal listings as “clerk-crier,” and Czuleger had to open court by announcing Williams arrival on the bench.

“I think I started at $8,000 a year, which seemed like a ton of money then,” the assistant presiding judge explains.

Williams, Czuleger says, “had a wealth of knowledge about life, putting aside the law, just was a wonderful, wonderful mentor for me.”

The jurist adds:

“I worked all day for him writing legal memorandums and crafting some opinions on occasion, and then went to law school at night and studied on the weekends. I didn’t have much of a social life for those years.”

While working for Williams, Czuleger met federal prosecutors and must have impressed some of them, because the local U.S. Attorney’s Office offered him a job while he was waiting to learn his bar results.

On his second day as an assistant U.S. attorney, Czuleger recalls, he argued his first case before the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and he tried his first case the next week.

“You don’t know any better when you’re young,” he comments. “You’re willing to do anything and everything. I’ll never forget, it was a two-defendant bank robbery with an insanity defense. And I had never tried a case in my life, and here I am with a two-defendant bank robbery in federal court. It came out fine, both got convicted. I’m not sure I knew what I was doing. I figured out how to cross examine a psychiatrist over the weekend, and I put my psychiatrist on, and it all seemed to come out in the wash.”

His immediate supervisor, now himself a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, observed part of the trial, Czuleger remembers.

“During the trial I turned around and he’s sitting in the first row. And he watches for a while, and at the break he goes, ‘Do you need anything?’ Well, I didn’t know whether I needed something or not. But I said, ‘No, I don’t think so.’ And he goes, ‘Okay, fine.’ And he left. It’s not like that now. I understand they have supervision and training and everything. But it was a great way to get thrown in the deep end and learn to swim.”

While an assistant U.S. attorney, Czuleger remembers, he helped pioneer use of the then-new law permitting forfeiture of assets used in drug trafficking.

“We decided to try it out,” he explains. “It was like a five-defendant no-dope drug conspiracy that we went on tax, and we went on drug conspiracy, and we did forfeiture, and we went out and we seized all the houses and the cars. Well, that’s usual now. Back then that was highly unusual. And it was an interesting experience, because the defense lawyer says, ‘We want bond to set and he’s got this house.’ And I stood up and said, ‘No, we seized that.’ ‘Well, he’s got the second house.’ ‘No, we seized that.’ ‘Well, he’s got these cars.’ ‘No, we’ve got those.’ And it really caused quite a flurry of calls from the defense community, because no one had ever used it before. So it was fun. And then we did a net worth tax case on him as well. And that was an interesting case, and a little bit on the unusual side.”

New Job

After two years as a prosecutor, Czuleger left to join Bird & Marella, becoming the first lawyer the firm’s two founding partners — both former assistant U.S. attorneys — hired on.

Terry Bird says the firm, now Bird, Marella, Boxer, Wolpert, Nessim, Drooks & Lincenberg, has since grown to 22 lawyers, but for about two years consisted of just Bird, Vince Marella, and Czuleger.

While the firm now specializes in white collar criminal defense, Bird says, in those early days they did “everything that came in the door.”

He recalls Czuleger convincing a judge on a challenging set of facts that one of the firm’s clients, a restaurateur, had not violated a noncompetition agreement by opening a new restaurant near one he had sold.

“He had a terrific ability to communicate in the courtoom,” Bird says, and would certainly have become the firm’s third partner had he stayed.

The fact that he did not, Czuleger says, was a result of his wife’s career needs, not his own.

Rebecca Czuleger is now a novelist who writes and gives writing seminars using the pen name Rebecca Forster. Her current works feature legal settings, usually with adventurous female protagonists.

But in the early 1980s, she was working in advertising, and had an attractive job opportunity in San Francisco. Partly motivated by their intoxication with the romance of the city, Czuleger says, the young couple decided to make the move.

“We loved San Francisco,” he recalls. “We used to go there, and we didn’t have children. When you’re young and you haven’t been married all that long you can do things like pick up and move.”

Czuleger was able to catch on with the Department of Justice Organized Crime Strike Force in San Francisco, working directly under Washington instead of through the local U.S. Attorney’s Office. But after a couple years by the bay, Czuleger got an offer to rejoin the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Los Angeles.

With a child now on the way, and with Rebecca Forster’s first novel in print, Czuleger says the pair decided Los Angeles was where they wanted to raise their family.

The jurist says that while he sometimes provides story ideas, he is “not allowed” to read his wife’s novels.

“We want to keep our marriage intact, so I don’t read the books,” he reports.

He recalls his wife asking him, while working on an early novel, for some details about a particular kind of legal proceeding and finding his answer far too involved for her purposes.

“She goes ‘No, no, no, I don’t need all of that, I just need to get them into bed by the end of the chapter,’” the assistant presiding judge remembers.

Rebecca Forster’s latest novel, “Privileged Witness,” is due to be published this month, and the first two chapters are available on her Web site, rebeccaforster.com. Its first chapter opens with the intriguing sentence:

“The half-naked woman came from the penthouse — she just hadn’t bothered to use the elevator.”

Czuleger observes:

“She always writes with a strong woman protagonist, usually a woman lawyer or a woman judge....She’s been optioned a couple times, but nothing has come of them. She much prefers working with New York than Hollywood.”

Czuleger came to the Superior Court after two years on the Los Angeles Municipal Court, to which he was appointed in 1988 by then-Gov. George Deukmejian. Though he is a Republican, he calls his a “merit appointment,” and says he was surprised when it happened.

|

|

|

U.S. District Judge David Williams swears in Czuleger as a member of the Los Angeles Superior Court on Oct. 15, 1990. |

He recalls:

“I said to my wife that night, ‘There’s something wrong with the system. I have never met the governor, I’ve never given him a dime, I’ve never had anything to do with politics and he just appointed me to the bench.’ And her response was, ‘Are you sure it’s you?’”

Presiding Judge Election

The court’s judges elect a presiding judge and assistant presiding judge in even-numbered years to serve two-year terms, and by tradition the assistant advances without opposition to serve as presiding judge.

MacLaughlin was unopposed when he ran in 2002 for assistant presiding judge, which while not unprecedented is distinctly not traditional. But associates like Judge Ronald S. Coen say they were unsurprised when no colleague chose to run against MacLaughlin for the post.

“The guy is bigger than life,” Coen comments. “It would just be a losing proposition. Everyone that he’s touched loves Bill.”

MacLaughlin credits Coen and now-retired Judge Howard J. Schwab for teaching him the ropes when he first came on the bench.

“The two of them had adopted me and undertook the impossible task of turning this sow’s ear into a silk purse,” he declares.

But Schwab says MacLaughlin was “more of a teacher than a student.”

“He was really bright and ahead of the game,” the retired judge says. “He was my tutor in civil law.”

Coen adds:

“All I did was answer questions....The truth is he took off running. He was the best criminal law student judge I have ever seen....I don’t think I had anything to do with it.”

Schwab calls MacLaughlin “a true genius,” and a “born leader,” describing him as “a combination of John Wayne and Albert Einstein” who is “at ease in the courtroom...and at ease in the saddle.”

Former Los Angeles County Bar Association President John Collins calls running the Superior Court an “impossible task,” but says that if anyone can do it, MacLaughlin can. He’s “a little bit smarter than all of us,” Collins says.

A Santa Clara graduate himself, Collins also finds a novel parallel between MacLaughlin and Czuleger, pointing out that the Santa Clara’s athletic teams are known as the Broncos.

“Two horses found each other,” he remarks.

Czuleger made his first run for assistant presiding judge in 2000, losing out to Judge Robert Dukes. Two years later, he joined his colleagues in making way for MacLaughlin, but in 2004 he tried again and won a three-way contest. Judge Mary House, who if elected would have become the first woman to hold the post, failed to get enough votes to force a runoff ballot.

Both Czuleger and MacLaughlin dismiss suggestions that the court’s judges are unwilling to be led by a woman — or by an African American judge, or by a judge who came to the court through unification, two other categories of jurist never yet chosen for a top leadership post.

MacLaughlin acknowledges that that there are judges whose votes in leadership contests depend, one way or another, on matters of race or gender.

“I think it is unfortunate that there are judges who would not favor [a female or African American] candidate, but it is also I think true that we have judges who would favor a candidate simply because they were from such a group,” he comments, adding:

“I don’t know how that balances out....Times are changing and the court is changing.... I believe the court’s ready for it.”

The distinction between judges who joined the Superior Court by appointment or election and those who arrived in 2000 by dint of unification is one of which few members of the court are even cognizant six years after the fact, Czuleger suggests.

“People just don’t know,” he insists. “I couldn’t tell you now, in this building, who came up through unification. I don’t think that’s an issue at all.”

As for women and African Americans, Czuleger points out that during his time on the court there have been two Hispanic presiding judges, and asserts:

“Most of my colleagues have enough common sense to say that they don’t want to do this job. We have some outstanding women and African Americans and Hispanics — we are blessed with so much talent on this bench....Will it happen? Yeah. Judges tend to vote for the person, not whether they were a former muni, or whether they are a Democrat or a Republican or a Deukmejian appointee or a Davis appointee....[I]t’s just a matter of time, I think.”

‘Public Service Guy’

Loyola Law Professor Laurie L. Levenson, who worked with Czuleger as a assistant U.S. attorney, says of the assistant presiding judge:

“I think he’s a public service guy.”

She cites his “easy manner,” but notes:

“That doesn’t mean he suffers fools — I wouldn’t say that.”

Czuleger spent some time on assignment in Div. Four of this district’s Court of Appeal in 1998, authoring 12 opinions, but Levenson suggests that appellate work is “too isolated for him,” saying he “thrives on” the heavy schedule of meetings that accompany an administrative post.

“He brings with him a bit of the federal style, which I know not everyone is enamored with,” she observes.

U.S. District Judge Nora Manella of the Central District of California, who also worked with Czuleger at the U.S. Attorney’s Office and served with him on the Superior Court, suggests that the strong women in the assistant presiding judge’s life have had a great influence on him, citing his three sisters and his wife, whom Manella calls “a pistol.”

She comments:

“He didn’t marry Rebecca because he was always looking for someone who would say, ‘Yes, dear.’”

Czuleger, she says, has a “very nice, self-effacing sense of humor,” adding that he “may be of all the men I know the one who most likes being around women.”

Czuleger’s two sons are both involved academically in theater, and Manella sees in the assistant presiding judge a “strong aesthetic gene..., which he somewhat does his best to conceal.”

In running for assistant presiding judge, Manella suggests, Czuleger was exhibiting the tendency to take responsibility that has characterized his professional life.

She comments:

“I don’t think it’s the adulation, if any of that comes. I don’t think it’s the title. He just sees things that he thinks could be done better.”

It’s the same tendency, she says, she observed in him as a young assistant U.S. attorney who always asked:

“What needs to be done? Send me there.”

Copyright 2006, Metropolitan News Company