Wednesday, December 27, 2006

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

1897: District Attorney Engages in Feud With Los Angeles Police Chief

By ROGER M. GRACE

Twenty-Second in a Series

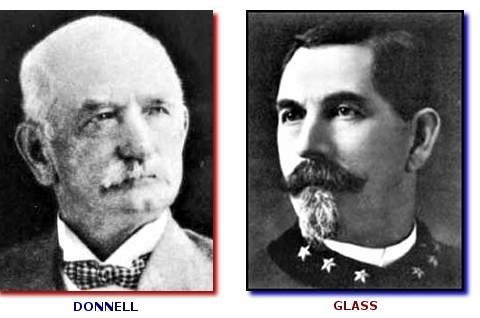

JOHN A. DONNELL, 24th district attorney of Los Angeles County, had a vocal detractor in the person of John M. Glass, chief of police of the City of Los Angeles.

Police and prosecutors are generally thought of as allies. While the depiction on TV’s “Perry Mason” of District Attorney Hamilton Burger and Police Lt. Arthur Tragg as virtually a team may have exaggerated the closeness, the common conception of a comradeship does square with reality. But that’s not how it was in 1897 when Donnell and Glass held their respective posts.

As I mentioned yesterday, Glass took a potshot at the DA for refusing to issue complaints against operators of Main Street dives who were fleecing naïve visitors to the big city from rural areas. Donnell cited lack of resources to prosecute minor crimes, and, the thought having struck him that such prosecutions might be the responsibility of city attorneys, he queried the attorney general if he were right.

On May 16, the Los Angeles Times reported that Donnell had received a response from the AG, William F. Fitzgerald. The news story quotes Fitzgerald as telling the district attorney: “[Y]ou are only required to appear before the Judge of the Police Court when he is sitting as a committing magistrate”—and was not required to handle misdemeanor prosecutions.

Nonetheless, local expectations were to prevail over advice from the state’s lawyer.

![]()

Glass next laced into Donnell for failure to institute vigorous prosecutions against petty bunco artists known as “sure-thing operators.” The Times on May 23 quotes Donnell as responding:

“The Chief of Police seems to have a happy faculty, whenever he is criticized upon his methods, or asked for reasons why he does not endeavor to suppress any existing evils in the city, of endeavoring to saddle off the responsibility upon some one else. The fact of the matter is, that no applicant since I have had charge of the office, has been refused a complaint against any of these so-called ‘sure-thing men,’ when applied for.”

Donnell’s response mentions that prosecutions in such cases were difficult for various reasons, including the tendency of persons who are charged with such offenses to restore the victims to their property, resulting in the victims becoming unavailable as witnesses. It continues:

“[T]he statements of the Chief of Police that we have refused to issue complaints appears to be a subterfuge by which he endeavors to shirk responsibility and create a halo of glory and virtue about his own head.”

![]()

On June 3, the city police commission directed Glass to report back as to why he hadn’t succeeded in cracking down on illegal Chinese lotteries. A report in the Times on June 8 contains Glass’s written response to the commission submitted the previous day. In it, the chief blames Donnell.

Glass’s report sets forth that about a year earlier, he “appealed personally to the police courts”—that is, made ex parte communications to the judges—to impose stiffer fines than the standard $10 ones…but was told he “would have to see the district attorney” who had agreed to a policy of light fines in return for guilty pleas.

The following is, by today’s standards,

truly bizarre. The chief of police recites in the report that he asked Donnell

to “try all Chinamen arrested for selling lottery tickets and conducting

lottery, by jury, and to let me know when jurors were to be summoned” so he

could send his officers into the business community to round up veniremen. This

was an approach which would, according to the chief, “surely secure convictions.”

The following is, by today’s standards,

truly bizarre. The chief of police recites in the report that he asked Donnell

to “try all Chinamen arrested for selling lottery tickets and conducting

lottery, by jury, and to let me know when jurors were to be summoned” so he

could send his officers into the business community to round up veniremen. This

was an approach which would, according to the chief, “surely secure convictions.”

Under English law, imported here in colonial days, when there were not enough summoned veniremen to complete a panel of jurors, the sheriff could go out and round up townspeople to serve. By 1897, this procedure was expressly authorized by Code of Civil Procedure §226—which permitted a judge to “direct the sheriff or an elisor chosen by the court forthwith to summon so many good and lawful men of the county, or city and county, to serve as jurors, as may be required.” Glass’s concept of conscripting persons presumed to be biased in favor of one side was hardly within the contemplation of the law.

Glass’s report to the commission also includes a retort to Donnell’s insistence that he had never failed to prosecute an alleged bunco swindler. Glass maintains he never said that Donnell had refused to prosecute such cases but, rather, alleges that the DA customarily permitted such delays in the proceedings that by the time of trial, the fleeced visitors were no longer around to testify.

The report suggests that the City Council should “employ an able attorney to prosecute our cases in the police courts”…though grumbling that he didn’t “see why the District Attorney’s office should not furnish a deputy for this department.”

![]()

Donnell could have taken the firm stance that, under the law, as confirmed by the California attorney general, the Office of District Attorney is not charged with the prosecution of misdemeanors, and that his office would leave such cases to those designated by law to handled them—period.

Instead, the DA caved in, recognizing that popular sentiment was in favor of a crackdown on the lotteries. While his vow to cooperate in Glass’s efforts was reported by the Times on the morning of June 8, the mood of the electorate, which may well account for his acquiescence, is reflected by an editorial that night in the Evening Express, declaring:

“Public opinion will uphold the authorities in resorting to extreme measures in this work of reform. It cannot begin too soon nor be prosecuted with too much vigor.”

The Times’ article of June 8 quotes Donnell as invoking the attorney general’s advisement, but going on to say:

“In spite of this I do not want to be mean about the point, and if Chief Glass and the police courts will give us a chance I am willing to detail a deputy to spend his time for a whole month trying lottery cases and doing nothing else, occupying the time of the police courts to the exclusion of all other misdemeanor cases. Let the police work up satisfactory evidence and be able to identify the Chinese prisoners; let the Chief send out his officers to the stores and select substantial business men, men like [grocer Hans] Jevne and [grocer John R.] Newberry, as jurors, and then we can go ahead and with jury trials attempt to convict and to secure heavy fines. If several such cases were carried through and as heavy a fine as is allowed by law [$500] imposed, I believe it would have a strongly deterrent effect on the lottery business. I have made this proposition in good faith, and am willing to stand by it.”

(I’ll be mentioning Jevne again; his store was right where the MetNews offices now stand. Newberry had several grocery stores in town—and had no connection with the J.J. Newberry dime stores.)

Donnell’s rejoinder points out that if he had not agreed to imposition of token fines, the defendants would have demanded jury trials, which would have been time-consuming and expensive, probably with nothing gained, the cases being difficult to prove. The statement adds:

“But it seems to me that if I had a hundred policemen at my command, I could shut up the Chinese lotteries….”

How could he gain the services of 100 policeman? Here’s Donnell’s reasoning: any citizen may make an arrest for a crime committed in his or her presence; Glass could “hire all the men he wants to act as stool-pigeons”; citizen-spies spotting a lottery could effect an arrest and call for the police.

Donnell’s conclusion is: “It will be a very difficult undertaking, but it ought to be tried.”

![]()

While Donnell’s citizen-spy approach was not implemented, Glass’s plan was. There were massive arrests and, with the acquiescence of the district attorney, the police sought to round-up businessmen to act as jurors, they being presumed to be prone to vote for convictions. However, another propensity of businessmen was to resist being herded into a courtroom without notice…and police were somewhat more inclined to back down to a firm “no” from a well-connected civic leader than from a denizen of skid row.

The Express’s Page One lead story on June 29, 1897 tells of a unanimous resolution of the police commission “calling upon all good citizens and especially merchants and business men to give up a portion of their time to service on jury, if necessary, for the lottery cases.”

That newspaper—which on June 25 editorialized that “the selection of jurymen should remain where it belongs, with the Police Department”—ran an editorial on June 30 with the heading, “An Urgent Duty,” admonishing:

“Instead of throwing obstacles in the way of the police, the merchants and property owners should do all in their power to assist the work of reform. It is idle for the authorities to attempt to crush out this evil unless they can have the support of those who are most concerned.”

![]()

Again shying away from an insistence that misdemeanor cases were simply not his to prosecute, Donnell sought a compromise. While adhering to the stance that he was not expressly responsible for trying misdemeanors, he acknowledged that the Los Angeles city attorney had the explicit duty to prosecute only those offenses defined by the City Charter and city ordinances. So, proposing a splitting of a baby, he called for the county Board of Supervisors to agree to a solution already approved by the City Council: each body would pay half the $100-a-month salary of Deputy District Attorney Joseph Chambers, who would be assigned to prosecuting misdemeanors in Los Angeles city police courts.

The board declined the request—but not because Donnell had no duty to prosecute misdemeanors. As recited in the June 10 issue of the Times:

“This request was denied by the board on the ground that it had no legal right to do as requested unless the District Attorney’s office was positively unable to do the work. As no evidence to that effect had been placed before the board, it refused to make the $50 per month allowance.”

So, the board, rather than disavowing any obligation to fund prosecutions of misdemeanors—a position that would have been supported by an attorney general’s opinion—proclaimed full responsibility for those prosecutions…and forfeited a 50 percent subsidy offered by the City of Los Angeles.

![]()

Donnell’s decision not to seek another term was reported by the Times on March 30, 1898. The article notes:

“But Maj. Donnell’s decision does not necessarily mean that he will retire from public life. On the contrary it is quite probable that he will be a candidate for the Republican nomination for Congressman from the Sixth District.”

Donnell had run for Congress once before. In 1886, running as a Republican, Donnell narrowly lost the race for a congressional seat from Iowa to James Baird Weaver, who had been the 1880 nominee for president of the Greenback Labor Party. (and in 1892 was the Populist Party candidate, winning four states).

But Donnell’s candidacy to be a congressman from California did not materialize.

The Times’ political column of Sept. 13, 1898, says:

“In the Seventeenth Assembly District, W. S. Melick will have some strong opposition in his effort to secure a renomination. Maj. Donnell, the District Attorney, has entered the race against him and will put up a strong fight.”

As it turned out, Melick was the only nominee at the Republican county convention that year for the Assembly seat he presently held.

Donnell’s political career started with his election as clerk of the District Court of Keokuk County, Iowa, after his service in the Civil War, continued with his winning the office of district attorney of Iowa’s Sixth Judicial District in 1882, and ended with his four years as Los Angeles County DA from 1895-99. Donnell, born in Indiana on April 13, 1838, died in Los Angeles on March 13, 1913.

Donnell’s nemesis, Glass, was born around 1843 in Tennessee. He was mayor of Jefferson, Indiana, from 1883-85, and was hired as chief of police here on July 17, 1889. Glass is credited with various reforms. During the year he was spatting with Donnell, 1897, the new police station, a three-story brownstone, was opened at 318 W. First St. The $50,000 structure was razed in 1955 after police moved into the $6 million Parker Center. Glass served as chief until Jan. 1, 1900.

Copyright 2006, Metropolitan News Company