Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

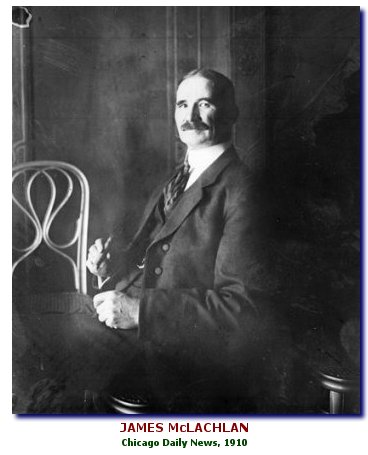

McLachlan, Dillon Compete Fiercely in 1892 DA’s Race

By ROGER M. GRACE

Nineteenth in a Series

JAMES McLACHLAN and HENRY C. DILLON headed into the final days of the 1892 campaign for district attorney with resolve, each going in for the kill.

“Candidate Dillon...says he is after District Attorney McLachlan’s scalp,” a Los Angeles Times article of Oct. 27 says.

Dillon, backed by the Democrats and Populists, had charged in a speech in Downey on Oct. 15 that expenses of the Office of District Attorney had burgeoned since McLachlan took it over in January of the previous year. He also alleged that the incumbent brought a futile action against Southern Pacific to enforce a judgment for back taxes just for show, the action being time-barred.

![]()

Two weeks later, McLachlan, speaking in Long Beach, finally responded in a comprehensive manner, departing from his usual long-winded rhetoric on the national issue of tariffs. That Oct. 29 talk includes this assertion:

“[Dillon] says that during the first year of my incumbency the county paid the sum of $2478.96 for special counsel having been employed to assist the District Attorney of this county, and ingenuously conveys the idea to the public that the sum was paid to assist me. He cites nine different items in proof of this statement, while these items were taken shows that with a single exception they were for services rendered during my predecessor’s incumbency.”

The one exception, as McLachlan explains it, was a $250 payment to outside counsel whose opinion was requested by the state Board of Examiners regarding the validity of courthouse construction bonds; McLachlan couldn’t provide the opinion because he was representing the county in the sale of those bonds.

As to Dillon’s contention that the total expenditures of the office in 1891 was $18,000, McLachlan’s speech contains the retort that he doesn’t know where Dillon got that figure “unless he has also charged up to me the cost of the upper story of the new court house, in which the new district attorney’s office is located.”

The speech, appearing in all three major Los Angeles newspapers on Oct. 30, continues:

“But Mr. Dillon’s most glaring misrepresentation of my record is where he refers to the number of criminal cases that I have had to deal with. These are his words: ‘During his term of office to date, Mr. McLachlan and his 10 assistants have had the management of but 276 criminal cases, big and little, being less than 13 cases per month, and less than two cases per deputy per month.’

“Now, Mr. Dillon says he is a lawyer, and there are those who will say that he is an honorable gentleman. He knows where the record of the criminal cases is kept, and he knows, if he has ever examined the record, instead of my having had the management of 276 criminal cases during my term, that I have the management of over 2000 such cases. What will I say of the individual who will thus misrepresent the record that he pretends to give in his mad attempt to defeat the maker of that record?”

As to those 10 assistants...the incumbent is quoted as declaring that he has only six, remarking of Dillon:

“It is probable that his vivid imagination classifies the typewriter [that is, person who types] and a deputy sheriff as district attorney’s deputies, but even then he falls two short of 10. If Mr. Dillon had fairly stated the facts, he would have stated what the record shows—that I have not only done the business of the county without the aid of special counsel, but that I have done the work with three less deputies than my predecessor had.”

With respect to the Southern Pacific litigation, McLachlan says he did not make a campaign pledge to file a complaint because he didn’t know about the matter until two weeks after he entered office, and that there had so far been two rulings in the case that the action was not time-barred.

![]()

The Los Angeles Herald, a Democratic Party partisan, comments in an Oct. 30 editorial that “notwithstanding Mr. MacLachlan’s denials,” the auditor’s report for 1891 does show payments to outside counsel in the amount Dillon claimed. This did not, however, refute McLachlan’s explanation that all but $250 of the sum was for expenses incurred before he took office.

A Nov. 5 article in the Evening Express, a Republican newspaper, observes that Dillon was the only candidate hurling personal attacks on his opponent and charges that he “has sought, by distorted presentations of facts, and unfair deductions therefrom, by insinuations, slurs and direct and willful misstatements, contradicted by himself at different times, to blast the fair name of a man he does not know, and to malign an official administration the best of the office this county has had for years.”

The Times’ editorial of Nov. 6 says:

“The Republican candidate for District Attorney has been assailed by the organs of both the Democratic and People’s parties more viciously than any man on the ticket; but the people of this county know that he is industrious and competent, and has made a first-class official, and will reelect him.”

Appended to the editorial is the text of an affidavit executed the previous day by four members of the Board of Supervisors, with the preface that it “settles one of the principal falsehoods circulated against McLachlan by his antagonist, H. C. Dillon.”

The affidavit declares “that not one dollar has been paid out for legal services rendered to the county in aiding Mr. McLachlan; that Mr. McLachlan, at the commencement of his term, expressed a wish that he be allowed to alone discharge the duties of District Attorney; that certain county matters then in the hands of Campbell, Houghton & Silent were by those gentlemen withdrawn from, at the wish of Mr. McLachlan” and that the firm was paid for its services to date.

![]()

The election adversaries continued to accuse each other of distortions in statements issued right up to the end.

In a letter to the editor, published by the Times on Nov. 6, Dillon castigates his rival for the timing of the Long Beach speech, saying that “he has taken advantage of my absence in the Antelope Valley to attack my character for truth and veracity, and to call me a falsifier of the records,” which he characterized as “most cowardly.”

Dillon explains in the letter how he reckoned that the incumbent had handled only “276 criminal cases, big and little,” saying:

“Mr. McLachlan claims that I have misrepresented his record in criminal cases. I did not deem it necessary, and I do not now think it necessary, to raise to the dignity of criminal cases drunk and disorderly, disturbing the peace, or petty violations of law, cognizable by justices’ courts, only....”

A letter to the editor in the Times’ Nov. 7 edition from McLachlan retorts: “If Mr. Dillon ever gets to be district attorney he will learn that the city attorney attends to the ‘drunks’ under the city ordinance, and that he will not have that kind of work to do.”

![]()

As it turned out, Dillon did get to be district attorney. The tally in the Nov. 8 election was 10,205 votes for Dillon, 9,296 for McLachlan, and 1,018 for the Prohibitionist candidate, W.E. Cox.

While it is true that it was a “Democratic year,” with Grover Cleveland regaining the presidency that was wrested from him four years earlier, that doesn’t explain Dillon’s victory. Although the Los Angeles electorate sided with Cleveland, it also favored several Republicans seeking county offices.

Party politics had perhaps diminished in significance in 1892. In light of new legislation, as reshaped by a state Supreme Court decision on Oct. 15, it was no longer possible to vote a straight party ticket by stamping an “X” by the name of the party at the top of the ballot.

It might well be speculated that Dillon made such an impact with his Oct. 15 exposé that McLachlan’s rebuttal in the waning days of the campaign came too late to dislodge notions that had set in.

An objective examination 124 years later of Dillon’s Oct. 15, 1892 charges, McLachlan’s Oct. 29 rebuttal, the further statements in letters to the editor, and the various affidavits that were produced, would seem, ineluctably, to lead to the conclusion that the Times was right in concluding in its Oct. 30 analysis:

“Mr. Dillon did not confine himself to the record, but drew freely on his imagination for campaign material, and did not hesitate to stretch a point where anything could be gained.”

![]()

Dillon’s term in office as district attorney, from January 1893 to January 1895, was uneventful.

The district attorney did not pursue the action against Southern Pacific for $50,000 in back taxes.

An editorial in the Express on Oct. 8, 1894, endorsed the Republican candidate for district attorney, John A. Donnell, and did not mention the Democratic-Populist nominee, E.C. Bower, by name. The gist of it was that Dillon was a Democrat, he had done a shoddy job as DA, so voters should elect a Republican.

The editorial mentions that Dillon had spent nearly 30 days that year in Sacramento, lobbying, and discloses:

“In October, ’93, Mr. Dillon was absent ten days; in April, two weeks; in July, three weeks, or a total of eighty-two days in nineteen months. During this nearly three months’ absence Mr. Dillon drew a $333.33 a month salary, so the county has paid him $1000 for time spent in vacations.”

![]()

Nonetheless, after leaving office, Dillon was dissatisfied with the amount he had been paid. His term was two years, and he was compensated for 24 months.

Not enough, Dillon declared. His term, by law, began on the first Monday following Jan. 1, 1893—which was Jan. 2—and ended when his successor took office on the first Monday following New Year’s Day in 1885, Jan. 7. As he figured it, Jan. 1, 1895 marked the completion of 24 months of service, and he wanted to be paid for the five days he was in office after that.

Dillon brought an action in mandamus against the county auditor to compel him to pay out an additional $54.50. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Lucien Shaw—later to become chief justice of California—granted the writ, and the county appealed.

The appeal was heard by a department of the California Supreme Court (the Court of Appeal not yet having come into existence).

Representing the county was the new district attorney, Donnell, and his chief deputy, George Holton, a former DA. Dillon represented himself, along with M.W. Conkling, who went on to become an Imperial Superior Court judge, then San Diego city attorney.

Shaw’s decision was affirmed.

Dillon later served in Long Beach as president of the school board and as city attorney, as well as a Los Angeles Superior Court commissioner.

In his earlier days, in Colorado, Dillon was a proponent of women suffrage. On Aug. 15, 1877, he was a speaker at a rally in Denver in favor of that movement. In his later days, he was an advocate of the initiative and referendum, serving in 1896 on the executive committee of the newly formed National Direct Legislation League.

In 1900, he became

president of the Los Angeles-based Yankee Doodle Oil Company, and proceeded to

advertise for investors. He was listed in ads as general counsel for the

Eastern Railroad Company, as well as “Ex-District Attorney of Los Angeles Co.”

The vice president was John D. Fredericks, identified as deputy district

attorney. Fredericks became the county’s DA in 1903.

In 1900, he became

president of the Los Angeles-based Yankee Doodle Oil Company, and proceeded to

advertise for investors. He was listed in ads as general counsel for the

Eastern Railroad Company, as well as “Ex-District Attorney of Los Angeles Co.”

The vice president was John D. Fredericks, identified as deputy district

attorney. Fredericks became the county’s DA in 1903.

Dillon died April 10, 1912, following a nervous breakdown.

![]()

McLachlan and another former DA, George S. Patton, competed in a congressional race in 1894 which was that year’s hottest contest, and one in which the name of a third ex-DA, Stephen M. White, was bandied about.

Editorial attacks on Patton by the Express were incessant. Rather than centering on Patton’s inability to complete his term as district attorney owing to frail health, and the prospect that he could not withstand the rigors of service in the House of Representatives, the editorials hammered away at the theme that Patton, a Democrat, would be the puppet of the Democrat White (whom it denominated “Boss White”), a member of the U.S. Senate from California.

McLachlan was handily elected, serving from March 4, 1895-March 3, 1897; failed to gain reelection; was elected to four successive terms, serving from March 4, 1901-March 3, 1911; and lost a race for reelection in 1910. He died Nov. 21, 1940.

Copyright 2006, Metropolitan News Company