Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

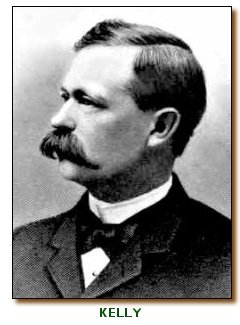

Frank P. Kelly: Last DA of Wild West Era, Sworn In on 35th Birthday

By ROGER M. GRACE

Seventeenth in a Series

FRANK P. KELLY stepped into office as Los Angeles County district attorney at the tail end of the “wild west” era…and when he stepped out of office, it was the “Gay ’90s.”

Kelly commenced his service as the county’s 21st chief prosecutor on Jan. 7, 1889 and exited when his successor was sworn in on Jan. 5, 1891.

The “wild west” era is generally considered to have stretched from the end of the Civil War, in 1865, to 1890 when the census showed a string of settled territory from the east coast to the west coast. The “Gay ’90s”—a term coined in 1926—describes an upbeat period of frivolity, business expansion, inventions, and massive immigration.

Los Angeles County obviously was not transformed all at once within the confines of those two years that Kelly was in office from a collection of frontier towns with dirt roads, bawdy houses and lynch posts into a cosmopolitan urban area. Actually, by the end of the “wild west” period, L.A. County had become fairly tame. Streets were being paved, sewers were being installed. There were electric cable cars…but still there were stage coaches, and the horse remained the primary means of transportation, the automobile being but a curiosity the longevity of which was in doubt. The telephone and electric lights were here…in some quarters of the county.

In that two-year period, locally, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher was formed, the first “Tournament of Roses Parade” took place in Pasadena and an electric generator was installed in that city, Orange County was founded (carved out of the southeast part of Los Angeles County), the Veterans’ Cemetery at Wilshire and Sepulveda was dedicated, Fort Street, south of First Street in downtown Los Angeles, was renamed “Broadway,” and Volney Howard, a former district attorney and one of the first two judges of the Los Angeles Superior Court, died.

Taking a broader view, the Eiffel Tower was opened, the Wall Street Journal debuted, the Sherman Antitrust Act was enacted, the Brooklyn Dodgers became a National League team (losing its first game to the Boston Beaneaters) and, in art, the Impressionist Period began.

This was the time—a busy, spirited, buoyant, transitional time—when Frank P. Kelly was district attorney. The pioneering and adventurous days when William C. Ferrell served as the first district attorney for this county (as well as San Diego County), in 1850-51, the days of primitive justice where roving judges decided on horseback disputes over such matters as who owned herds, were far in the past. The prospect of women serving as judges at the lowest and even highest levels of the state judiciary, and Chinese not only qualifying for citizenship but for California Supreme Court membership, could have been foreseen then by only the most prescient. The days lying ahead of online legal research and decisions posted on the Internet surely were beyond imagination.

Kelly, though he didn’t know it, stood on a bridge between eras in our county’s history.

![]()

As you’re apt to discern

from his name,

Kelly was an Irish American. His parents had immigrated to America in 1836 from

the county of Tyrone, in the north of Ireland.

A look at a biographical sketch of Kelly appearing in the Oct. 30, 1888 edition of the Los Angeles Evening Express, a few days before the election for district attorney, shows that he had scant formal schooling, and was self-taught. Before entering law, he was a printer and newspaperman. He flitted from job to job, place to place, but was constant during his adult years in his devotion to the Republican Party.

Kelly was born Jan. 7, 1853, in Philadelphia. When he was 10, he had to leave school to help support his family, his father and oldest brother being off fighting in the Civil War. His first job was as an errand boy in a drug store, and at 13, he landed a job in a print shop.

Kelly’s father and brother returned home at the end of the war, but the father died the following year. Kelly went to California to live with an older sister and her husband, arriving in San Francisco by ship in March, 1867.

He worked for about five years in a print shop in Sacramento.

The Express makes no mention of Kelly having gone to work around 1872 as a printer in Nevada, but apparently he did. The Nevada State Journal in Reno on Oct. 10, 1905, carried a story bearing the headline, “Old Time Printer Visits Reno.” It says:

“Frank P. Kelly, an attorney of San Francisco, the city yesterday on his way to Hawthorne, where he is called to look after some legal business. Thirty-three years ago, Mr. Kelly was an employee in the Journal office, being but two years after this paper started, and he could not pass through Reno without calling upon his first love….”

![]()

The Express says that Kelly worked for about two years for Jeffries’ Law Printing Office in Sacramento, where briefs, transcripts, and reports of California Supreme Court decisions were printed. He thus got his first exposure to law. Having educated himself since he left school by reading, it might be assumed that he not only printed legal materials, but examined the contents.

He was 20 when he opened a print shop and began publishing his own newspaper, The State Capital Globe. He sold his operations later that year—1874—and moved to San Francisco where he made a bundle through some good investments, then lost his savings through some bad ones.

Kelly went to work in the winter of 1877 for the Sacramento Bee, remaining there just a few months. In April, 1878, he purchased the Tehama Tocsin, and became its publisher.

The following year, Kelly did what other California journalists have done through the decades: run for public office. Few have succeeded. (Those who have include Oakland Tribune publisher William F. Knowland, the U.S. senator Republican leader during the Eisenhower Administration, who was trounced in his bid for governor in 1958; and KABC-TV anchor Baxter Ward, a two-term member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, defeated in his try for a third term by Mike Antonovich, who still holds the seat.)

Kelly ran for the Assembly in 1879 from Tehama and Colusa counties, and lost. The 1888 article in the Express, a Republican newspaper, explains that in light of heavy Democratic registration in the district, winning “was a forlorn hope” for a Republican, but comments that “the organization of the Republican party and the spirit of its principles demanded that the ticket be nominated and maintained.”

For four years and seven months, Kelly published the Tehama Tocsin, then sold it. As the article in the Express tells it:

“[T]he incessant recurrence of malarial fever on the Sacramento River, on which Tehama is located, so affected Mr. Kelly’s eyesight that he was compelled to leave that country, and by order of his physician removed to Santa Barbara where he was engaged for a while as editor of the Press, leaving that to accept the more pleasant and lucrative position of cashier and bookkeeper of the Arlington Hotel. During all these years, Mr. Kelly never forgot the ultimate object of his life, and was ever studying the deep problems of law.”

![]()

The year of 1884 was a hectic and varied one for Kelly. In January, he was put in charge of a newspaper in Los Angeles known as the “Republican.” That was a brief job, as was his next one. He ran the Evening Express, until it came under new ownership in August of that year. And before the year was over, Kelly was admitted to the practice of law in the state, and went into practice.

That marked the end of his endeavors as a printer and a journalist. He was, by the way, neither the first nor the last DA tied to those fields. One of Kelly’s predecessors, Volney Howard, was editor of the Mississippian in Vicksburg, Miss., during the 1840s and of the Dispatch in San Francisco in the early 1870s. A successor, James C. Rives, who was elected as district attorney in 1898, had owned and edited the Downey Weekly Review while studying law.

In 1885, a Republican, J.W. McKinley, became Los Angeles city attorney, and made Kelly his assistant. McKinley left office after two years (going on to become a Los Angeles Superior Court judge in 1889 and Los Angeles Bar Assn. president in 1918). Kelly was hired immediately as clerk of a state Assembly committee headed by George W. Knox, a Republican.

![]()

Complaints of an inadequate number of judgeships on the Los Angeles Superior Court are nothing new. Such grumbling was heard in the 1880s. Relief came. Here’s an editorial in the Los Angeles Times, published Feb. 4, 1887:

“LOS ANGELES is to have her two additional Superior Judges. The bill providing them has passed both houses and Gov. [Washington] Bartlett will not refuse to place his X-mark to the law. Now, with four superior judges, sessions of the State Supreme Court, a Federal judge, city and township justices, a police justice, and so on, Los Angeles will have as much law to the square inch as any town in the country.”

Kelly went to work as a clerk for one of the new judges, Harvey K.S. O’Melveny (a former president of the Los Angeles City Council and father of Henry O’Melveny, founder of O’Melveny & Myers). That job also lasted only a few months, and Kelly went back into practice, running as the Republican nominee for district attorney in 1888.

The Los Angeles Times endorsed him—well, actually, it embraced the entire Republican state, congressional, and county tickets. Its editorial on Kelly on Nov. 5, 1888, says:

“Frank P. Kelly is the candidate for district attorney. He is energetic and enterprising, and has some experience in that class of legal business, and promises, if elected, to organize his office on a basis that will secure its efficient administration, for which there is ever a permanent and imperative need in this great county, with its large and multiform needs. Vote for him.”

Kelly won by 2,630 votes, defeating incumbent J.R. Dupuy. He was sworn in on Jan. 7, 1889, his 35th birthday.

During his time in office, Kelly personally acted for the People in seven cases before the California Supreme Court and, as a private lawyer, represented the Board of Supervisors before that tribunal in an elections case. These were the times before there were courts of appeal, and in four of those cases, the hearing was before a panel of three Supreme Court justices.

Despite a keen interest in politics and a desire to hold public office, the post of district attorney was the only one to which he was ever elected. Kelly did not stand for reelection to that office; he had his eye on another one: the state Assembly. In a report on the Republican county convention, the Los Angeles Times’ edition of Oct. 5, 1890 tells of the party choosing its nominee for election to the Assembly from the Second Ward:

“S. G. Millard, in a few eloquent remarks, placed in nomination for the office Frank P. Kelly. He referred to him as a young man who had served the county honestly and efficiently as District Attorney. [Smiles.]”

The bracketed phrase is in the original.

There were four nominees, and 173 votes were cast. Kelly received only 10 of those votes.

![]()

Kelly practiced for awhile in Santa Barbara, then moved to the Bay Area. A Court of Appeal opinion of May 23, 1914, recites his testimony in San Francisco Superior Court in which he defined his present activity, saying: “I attend to the criminal business of the Southern Pacific Company in this city and county.”

The action was brought by a man against the railroad company, his former employer, based on its having effected his arrested for allegedly stealing a case of shoes. Kelly testified that he investigated the apparent theft and made out the police complaint. In reversing a $500 judgment against the railroad, the Court of Appeal opinion says:

“In our opinion Kelly was justified in taking the steps he did upon the information given him....”

A curious aspect of the case is that Kelly apparently acted as the prosecutor at the suspected thief’s preliminary hearing, held in police court. The opinion says:

“What we hold is that, in assuming, as the attorney and agent of defendant, to advise the officers that there was sufficient evidence to hold the accused and in preparing the complaint and causing warrant to issue and in subsequently taking charge of the examination, as we may infer he did, Kelly placed the defendant in the attitude of an accuser, but it remained with plaintiff to show that it acted through malice and without probable cause.”

It would seem that there was in San Francisco at that time something approaching the “private prosecutions” that have existed for centuries in England.

A 1909 report of the San Francisco Grand Jury contains a section headed “The Right of Citizens Not Holding Office to Contribute Assistance in the Prosecution of Crime.” It says:

“The public service corporations of San Francisco have, for a long time, furnished the State with special prosecutors in criminal cases where their interests have been concerned. Prior to and during the period of the graft prosecutions the following attorneys assisted in prosecuting various crimes on behalf of the corporations set opposite their names:

“....

“Frank P. Kelly, Southern Pacific Company.”

So, long before there were “private judges” in California, there were “private prosecutors,” like Kelly.

Copyright 2006, Metropolitan News Company