Monday, October 23, 2006

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Statue of County’s 17th DA Erected at Courthouse, Now Stands Near Harbor

By ROGER M. GRACE

Fourteenth in a Series

“ONE DAY, PERHAPS, a Homeric tale will be written of that great ‘battle’ which has been fought for some years in the Southland: the fight for the statue of the late Stephen M. White, former United States senator.”

That’s how an article begins in the Oakland Tribune on May 9, 1937.

I would somehow doubt that when you finish reading my columns on the statue, your comment will be, “My, wasn’t that a splendid Homeric tale?” But this is probably the only comprehensive rendition you’ll find of the history of that statue…one which many readers will recall from the days when it stood, from 1958-89, in front of what is now called the Stanley Mosk Courthouse—for most of that time, at First and Hill Streets. Not many, but a few, will recollect when it was mounted augustly on a seven-ton, 12-foot granite base at its original location, the site of a previous courthouse at Broadway and Temple Street.

The statue, first dedicated in 1908, has been located since 1989 at the entrance to Cabrillo Beach, near the harbor—representing fulfillment of a spirited decades-long effort by San Pedro to wrest the sculpture from the Los Angeles Civic Center. At this point, White’s legacy as the senator who brought the harbor to San Pedro (that harbor now known as the Port of Los Angeles) is perhaps more pertinent than his service from 1883-85 as Los Angeles County district attorney.

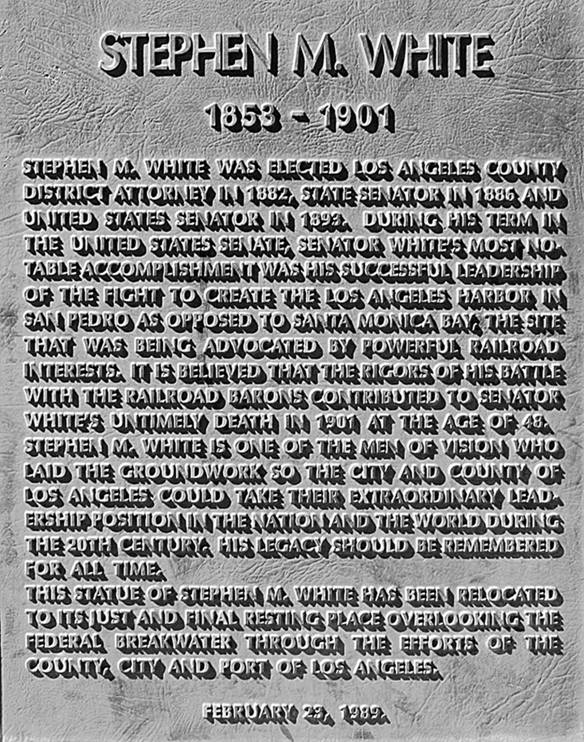

The plaque accompanying the statue appears below.

![]()

Prominent merchant Harris Newmark takes credit for coming up with the idea for a statue of White. In his book, “Sixty years in Southern California, 1853-1913,” Newmark says:

“The zeal with which White so successfully entered the conflict against [railroad magnate] C. P. Huntington in the selection of a harbor for Los Angeles was indefatigable; and the tremendous expenditures of the Southern Pacific in that competition, commanding the best of legal and scientific service and the most powerful influence, are all well known. Huntington built a wharf—four thousand six hundred feet long—at Port Los Angeles, northwest of Santa Monica, after having obtained control of the entire frontage; and it was to prevent a monopoly that White made so hard a fight in Congress in behalf of San Pedro. The virility of his repeated attacks, his freedom from all contaminating influence and his honesty of purpose—these are some of the elements that contributed so effectively to the final selection of San Pedro Harbor. On February 21st, 1901, Senator White died. While at his funeral, I remarked to General H. G. Otis, his friend and admirer, that a suitable monument to White’s memory ought to be erected….”

Harrison Gray Otis was a man who did not lack influence. He was publisher of the Los Angeles Times—a newspaper which had fiercely backed the selection of San Pedro as the site of the harbor.

The upshot of Newmark’s suggestion was that the White Memorial Fund Committee was formed which raised $25,000 in private funds to erect a statue. Newmark and Otis were members of its executive committee. So was attorney Joseph Scott, its secretary—who was later to be immortalized, himself, in bronze; a lifesize statue of him, erected in 1967, is to be found at the west end of the Mosk courthouse on the Grand Avenue side, facing the Music Center.

Given the support of the staunchly Republican Los Angeles Times and individual GOP loyalists such as Scott (who was to nominate Herbert Hoover for president at the party’s 1932 convention), there was no partisan aspect to the effort to pay homage to the Democrat White.

![]()

Whether to erect a statue was never much of an issue. Where to put it was.

By action of the Board of Supervisors, the question of whether there should be an “erection of statutes or monuments upon the Courthouse grounds of Los Angeles county” was submitted to voters at the Nov. 4, 1902 election. The ballot proposal made no reference to White though it was commonly understood that a statue of him (which by then had been fully financed) was the only one contemplated for the grounds.

A Times editorial appearing the day before the election proclaims:

“A vote in favor of the erection of the Stephen M. White statue on the Courthouse grounds is a vote in compliment of one of the greatest men the State of California ever produced—let us say the greatest, for it is the truth.”

The editorial goes on to observe that a vote in favor of permitting statues on courthouse grounds “will act as a fitting rebuke to the narrow minded men who have made voting upon this question necessary, when there never should have been any question upon it.”

An Oct. 25 editorial in the Los Angeles Express says: “As the late Stephen M. White was best known as a lawyer the courthouse grounds would seem to be the most fitting spot for a monument in his honor.”

Voters approved the measure—overwhelmingly within the City of Los Angeles, and by less of a margin in other portions of the county.

Deaf-mute artist Douglas Tilden was commissioned in 1905 to sculpt the 8-foot high bronze statue, which would stand on the Broadway side of the county courthouse.

![]()

A Times editorial appearing on the morning of the Dec. 11, 1908 unveiling of the statute says:

“[I]t is particularly fitting that this monument stand close to the courts of this county, in which [White] so often employed his great legal learning in the cause of justice and right, for the protection of the innocent and weak, and for the punishment of those whose deeds were a menace to society, regardless of their station in life, be that high or low.

“As

prosecuting attorney in the early days of his career, Stephen M. White left a

record worthy of the study and imitation of all who shall ever fill that

office. It may be said that during his incumbency no malefactor was brought

before the courts and allowed to slip through the meshes of the law, if proven

guilty, however able the talent opposed to the prosecution.”

“As

prosecuting attorney in the early days of his career, Stephen M. White left a

record worthy of the study and imitation of all who shall ever fill that

office. It may be said that during his incumbency no malefactor was brought

before the courts and allowed to slip through the meshes of the law, if proven

guilty, however able the talent opposed to the prosecution.”

The Times’ Dec. 12 news report of the previous day’s ceremony begins:

“Los Angeles county paid loving homage yesterday to the abiding memory of Stephen M. White, at the unveiling of the magnificent bronze statue of the late Senator on the Courthouse grounds. It is estimated that fully 20,000 persons gathered about the big public building, filling every bit of standing-room and overflowing into Temple Street and Broadway, out of range of the voices of the speakers, and unable to see the bronze figure....”

Following a “magnificent eulogy” to White delivered by former Gov. Henry Gage, the article continues, there “came the unveiling of the statute” by “Miss Hortense White, daughter of the Senator, [who] stepped bravely to the front and gently pulled at the cord that had the drapery in place, releasing the covering.” The report says:

“As the bronze likeness of Senator White was disclosed to view, all present bowed their heads in respect, while the school children sang ‘The Star Spangled Banner.’”

According to the article, Scott turned the statute over to the state, receipt of which was acknowledged by Warren R. Porter, the lieutenant governor (whose post was once held by White).

Hortense White was the great aunt of my e-mail pen pal, Lindalouise White De Mattei, who relates:

“When I was growing up in Los Angeles, we would pass by my Great Grandfather’s statue whenever we passed the Civic Center. My dad would casually point out that that was ‘The Senator.’ For years I considered it normal that there be a statue in his honor, after all, he was MY Aunt Hortense’s father. She was the great one in my eyes.”

![]()

The red sandstone courthouse in front of which the statue stood was severely damaged by the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, and was vacated. Even before it was razed in 1936, efforts were underway to effect the relocation of the statue to San Pedro.

A Reno (Nev.) Evening Gazette editorial of March 12, 1934, speculates that the statue “may be exiled to San Pedro.”

The May 9, 1937, Oakland Tribune editorial I alluded to at the outset of this column comments that the “[l]atest echo” in the battle over the statue “is the Governor’s veto of an Assembly bill to move the image from Los Angeles to San Pedro,” continuing:

“Three years ago we heard the first rumblings. Because of plans to raze the courthouse, on the lawn of which the statue had stood since 1905, the question of disposition came up....Proposal was made to move it to San Pedro because of White’s successful fight to secure recognition of the harbor. There were those who held to their sentimental affections. Ramona Parlor of Native Sons protested the removal. Of citizens who subscribed and paid some $30,000 to erect the statue only three remain today, and they would keep it for Los Angeles. They are Isidore Dockweiler, Hon. Joseph Scott and Hon. Reginaldo F. Del Valle.

“…[T]here are those who say they do not care if the statue is not, in the judgment of today, a ‘good’ one. It represents historic moments and a man who fought valiantly. The statue will be preserved, but it is likely the row between those who would move it to the harbor and those who would keep it in Los Angeles will have some new revivals. At least, it is one to show that men remember.”

More attempts at state legislation were to come in this battle for possession of a statue, a battle which was to continue for half a century. I’ll describe later developments in the next column.

Copyright 2006, Metropolitan News Company