Friday, July 7, 2006

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Los Angeles County’s First District Attorney: Job-Hopper, Politico, Recluse

By ROGER M. GRACE

First in a Series

The Los Angeles County Bar Assn., whose online “Virtual Museum” was spotlighted last Friday, isn’t the only local entity with fascinating material about its history posted on the Internet. The District Attorney’s Office for this county has a section on its website offering brief biographies of the 36 men who have headed the office since its founding in 1850.

Those biographies (taken from a book by Michael Parrish) are at http://da.co.la.ca.us/history.

The information is somewhat sketchy but where it piques interest—and mine was piqued—more about the historical figures discussed can, of course, be uncovered from other sources.

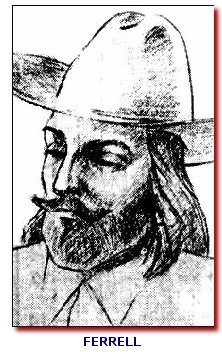

WILLIAM C. FERRELL was the first district attorney for this county. He’s the only DA of whom there’s only a drawing, not a photograph or oil portrait, on the website.

In “Lawyers of Los Angeles” by W.W. Robinson, his surname is spelled “Ferrill,” as it is in the 1850 U.S. census, but the spelling employed on the website is the one commonly used.

Ferrell was put up as a candidate for district attorney by a “secret junta of all the leading Californians, meeting at the residence of Don Agustin Olvera early in March” of 1850, according to the diary of Benjamin Hayes, who was elected as a judge of the District Court in 1852 and 1858. Olvera was himself backed by the powers-that-were in 1850 for a term as county judge (on a rung lower than judges of the District Court), and was elected April 1 of that year.

It was on that date that Ferrell, at the age of 37, gained election as district attorney…but was not elected to serve only this county. He became prosecutor for the “First District,” a trial court district encompassing both Los Angeles and San Diego counties—which were among the “original” counties established by legislation on Feb. 18, 1850, in anticipation of California gaining statehood (which came on Sept. 9 of that year).

The First District covered far broader terrain than that

comprising today’s Los Angeles and San Diego counties. What was to become

Orange County in 1889 was merely the southeastern portion of Los Angeles

County. Also, part of what is now Kern County was located in this county. (Kern

was formed in 1866 from a slice of the northern portion of Los Angeles County

and a hunk of the southern part of Tulare County.) Too, San Diego County in

1850 contained what are now the counties of San Bernardino, Riverside and

Imperial.

What was to become

Orange County in 1889 was merely the southeastern portion of Los Angeles

County. Also, part of what is now Kern County was located in this county. (Kern

was formed in 1866 from a slice of the northern portion of Los Angeles County

and a hunk of the southern part of Tulare County.) Too, San Diego County in

1850 contained what are now the counties of San Bernardino, Riverside and

Imperial.

The DA’s website says that a total of only 377 votes were cast in the election. Even given that under Art. 2, §1 of the 1849 California Constitution, only white males over 21 could vote, the scant number of ballots does seem remarkable in light of the enormity of the territory.

In balloting just in San Diego County, Ferrell received 79 votes to four for Miles K. Crenshaw. That’s according to William E. Smythe’s 1908 book, “History of San Diego, 1542-1908.” That book notes that Ferrell ran in that same election for county judge in San Diego and garnered only one vote (presumably his own) against 80 for John Hays, and vied with Thomas W. Sutherland for county attorney, garnering four votes to 71 for his rival. There were 157 eligible voters and two polling places in the county.

Robinson’s book mentions that at the first session of the District Court for the dual county district, on June 5, 1850, Ferrell, among others, was sworn into practice before the courts of the state. It does seem anomalous for a district attorney being elected before becoming admitted to practice in the state, but Ferrell was, at least, already a lawyer in North Carolina, according to Smythe. In coming to California, the author notes, Ferrell left behind behind two daughters.

![]()

The DA webpage on Ferrell says:

“His income as district attorney was largely derived from a ten percent cut of civil judgments as well as fees paid from guilty criminal defendants’ fines. In October 1850, when it became clear that the state legislature would soon require a district attorney in each county—drastically cutting his income—Ferrell promptly quit.”

(It appears from other information on the website as well as Robinson’s book that “1850” was a typo; it should have read “1851.”)

The thumbnail sketch on the DA’s website continues:

“He would serve in other public positions in San Diego through the mid-1850s, on the first County Board of Supervisors [1853], as county assessor [1854-55, 1857] and as district attorney of San Diego County [1859]. Then, apparently as a way to thwart his growing dependence on alcohol, in 1860 he moved to Mexico, building an adobe home with a vegetable garden and a large vineyard on a remote mesa south of Tijuana.”

Smythe reveals that Ferrell was also a member of the state Assembly, customs collector, school commissioner, and city trustee. The author characterizes the office-holder as “able” but “somewhat eccentric.”

![]()

The reason for Farrell’s departure from the U.S., Smythe says, “is somewhat obscure,” but that “the traditional reason is at least plausible.” The book recites:

“It is said that, being a somewhat testy man and having set his heart upon winning a certain case, it was decided against him; whereupon, he became enraged, banged his books down upon the table, and declared that, since he could not get justice in this country, he would quit it, and proceeded to do so.”

Smythe goes on to say:

“His San Diego friends kept him supplied with reading, and when they visited him, found him always well informed and, apparently, happy. The newspapers of the time contain many references to Ferrell, how he watched over San Diego from his mountain fastness, etc. He died June 8, 1883.”

A “hermit for 24 years” is how an obituary in the Fresno Republican describes him.

A retrospective in the San Diego Union-Tribune last year notes that in 1850, Ferrell and others “formed a corporation to develop a new town site near San Diego Bay, and that “[t]hey purchased 160 acres of land bounded on the east by what is now Front Street and on the north by what is now Broadway, but the location was largely abandoned after the Civil War.”

ISAAC K. OGIER was next to serve as Los Angeles County district attorney, holding that post from 1851-52. (San Diego now had its own district attorney, Ferrell’s erstwhile election rival, Sutherland.)

Ogier had been in private practice in Charleston, South Carolina; New Orleans, Louisiana (1845-46, 1848-49); San Joaquin, California (1849-50); and in Los Angeles since 1850.

The DA’s website says:

“In 1853, in the El Dorado Saloon, Ogier, Judge Agustin Olvera and other leading citizens organized the Rangers, a vigilante group that would grow to a hundred members and would lynch at least twenty-two people between 1854 and 1855. Ogier’s reputation seemed to survive, however. From 1854 to 1861, Ogier served as federal District Judge for the Southern District.”

Ogier, according to Robinson’s book, wrote succinct opinions—deciding cases without citation to authorities.

KIMBALL H. DIMMICK was the county’s prosecutor from 1852-53. His exploits will be dealt with in the next column.

BENJAMIN S. EATON was district attorney in 1853-1854 and was county assessor in 1857. According to the website:

“Eaton was a founder of Pasadena, then the Rancho San Pasqual, and later encouraged people from Indiana to migrate to the area in the land boom of the 1870s. One of Pasadena’s main streets, Fair Oaks, takes its name from Eaton’s home. Frederick Eaton, his son, became a major force in Los Angeles, serving as city engineer and mayor.”

Future columns will deal with some of the more colorful district attorneys of Los Angeles County including one who became mayor of Los Angeles, another who was father of one of the best known generals in World War II, and two who were indicted.

Copyright 2006, Metropolitan News Company