Thursday, October 6, 2005

Page 11

REMINISCING (Column)

Prohibition Creates Market for Canada Dry Ginger Ale

By ROGER M. GRACE

How did Canada Dry ginger ale gain popularity? Chalk it up to Prohibition.

The national ban on the manufacture, sale or transportation of alcoholic beverages (from 1920-33) was nearly as helpful to soft drink makers as it was hurtful to breweries, which had to turn to the making of other products. Canada Dry was probably the chief beneficiary.

That brand of ginger ale is, by the way, aptly named. It originated in Canada (in 1904) and is “dry”—in contrast to the sweeter and more flavorful “golden” ginger ale which derives its color from caramel. Canada Dry was first shipped to the United States from Canada in 1919, the year before national Prohibition went into effect. Its popularity was instant and bottling of the beverage (made from Canadian extract) began in 1921 at a plant in New York City.

A syndicated article appearing in newspapers in 1927 and 1928 was titled, “How Dry America Made Dry Ginger Ale a Billlion-Dollar Industry.” It recounted:

“[T]he dry law, boosting the sale of ‘soft’ drinks, boosted the sale of ginger ale more than any and boosted the sale of ‘dry’ ginger ale more than all. The boost wasn’t due to the fact that drinkers turned to dry ginger ale only as a substitute for booze; they took it up, too, as a complement to booze.

“There are many kinds of bottled soft drinks—root beer, birch beer, sarsaparilla, lemon, orange, charged waters and lime concoctions. Each of these has its army of followers. But ‘dry’ ginger ale apparently possesses certain qualities which particularly endear it to ‘hard’ drinkers as well as ‘soft’ drinkers. It may be the taste, which is not so sweet as so-called ‘golden’ ginger ale. It may be the belief, fostered by its makers, that dry ginger ale has the peculiar merit of breaking up the ‘raw’ quality in ‘cut’ liquor and neutralizing its injurious elements. And probably, too, the colorless look of ‘dry’ ginger ale adds to its popularity.”

The most common type of liquor in the United States during Prohibition—either smuggled in or concocted in bathtubs—was gin. And generally, gin was mixed with dry ginger ale (a combination vitually unheard of nowadays).

“[G]in-and-ginger-ale has become almost a national drink,” the 1928 newspaper article said.

On its website, Cadbury Schweppes plc, which now owns Canada Dry (and practically every other popular brand of non-colas), says:

“In the 1920s Canada Dry was a favourite mixed with ‘bathtub’ gin. An average bathtub filled with gin would make 2,560 highballs when combined with 1,280 bottles of Canada Dry.”

There were, of course, other brands of dry ginger ale during Prohibition—among them, Busch’s Extra Dry, made by the erstwhile manufacturer of Budweiser beer, and Pabst Dry Ginger Ale, produced by another former beer brewer. But it was Canada Dry that maintained the top position.

During Prohibition, Canada dry ads vaguely hinted that ginger ale was a mixer. For example, a 1924 ad in mentioned that it “blends delightfully with other beverages.”

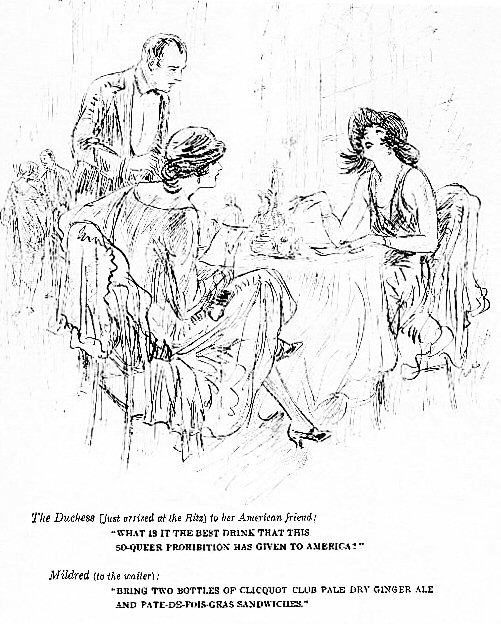

An ad that year for a rival ginger ale said: “And by the way Clicquot Club Pale Dry mixes deliciously with other drinkables.”

The company that manufactured Clicquot Club (which was ultimately purchased by

Canada Dry) had long made a golden ginger ale, but added pale dry ginger ale to

its line of soft drinks by 1920 to satisfy consumer demands. This ad appeared

in magazines in December, 1925:

By the time Prohibition ended, ginger ale had come to be thought of more as a mixer than a soft drink. The only major golden ginger ale to survive to the present is Vernor’s, on the market since 1880. That venerable product is next week’s topic.

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company