Wednesday, January 19, 2005

Special Section

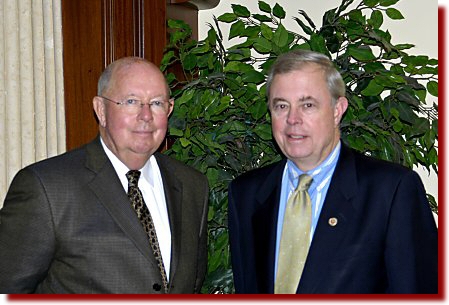

PERSONS OF

THE YEAR, 2004: Los Angeles County Bar Assn. President John J. Collins,

State Bar of California President John Van de Kamp

Attorneys John J. Collins and John Van de Kamp

Current LACBA, State Bar Presidents Played Major Roles in Shaping Fast Track

By DAVID WATSON, Staff Writer

It would be hard to guess, upon meeting John J. Collins or John K. Van de Kamp, that either man will turn 70 next year—though given continued good health both will.

But apart from that, the first impressions made by the two men could hardly be more different.

Tall, angular, and soft-spoken, Van de Kamp retains the boyish charm evident in photographs from his days as Los Angeles district attorney nearly 30 years ago. He responds to questions thoughtfully, quietly, sometimes hesitantly, and often at length, showing the instinct for the diplomatic turn of phrase that characterizes many a successful career politician.

Though he was not born to money, the courtly, urbane and reserved former California attorney general grew up closely related to it. Uncles founded the Van de Kamp bakery and Lawry’s restaurants, and though his father was a bank teller and his mother a grade-school teacher, they benefited from the family’s success while Van de Kamp was still young.

Collins, stocky and round-pated, is as outspoken as Van de Kamp is understated. With four decades in the courtroom behind him, he seems to have gotten used to saying what he thinks with the confidence of a man who is willing to deal with the consequences.

He personifies the no-nonsense litigator, likely to answer a question in less time than it took to ask it—and there is little danger the questioner will have difficulty hearing him. Though his father became an attorney, and they later practiced together, when John Collins was born, James E. Collins was an insurance adjuster—at one time, his son recalls, the only adjuster for Farmers Insurance in San Diego and Orange counties.

Van de Kamp and Collins, two Southern California natives born 10 months apart, have influenced California’s legal system and legal community in many ways during a combined 86 years of law practice and bar organization activity.

Collins, whose one-year term as president of the Los Angeles County Bar Association began July 1, was a member of the State Bar of California Board of Governors when the bar was put on a virtual standstill by then-Gov. Pete Wilson’s dues bill veto. He has served on the California Judicial Council and as president of the Pasadena Bar Association, California Defense Counsel, the Association of Southern California Defense Counsel, and the Los Angeles Chapter of the American Board of Trial Advocates.

Van de Kamp, whose 11-month term as State Bar president began in October, was the first federal public defender in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California and was elected Los Angeles district attorney and California attorney general twice each before mounting an unsuccessful campaign for governor, losing in the Democratic primary to now-U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein.

He has served as a LACBA trustee and for many years has been a member of the LACBA contingent at the Conference of Delegates of California Bar Associations and its predecessor, the State Bar Conference of Delegates.

But for attorneys litigating in California courts, the greatest impact the two have had might have been their roles in shaping the effort to reduce delays in moving civil cases through the court system—or, as it is usually known, fast track.

It was an effort on which the two men—jointly honored as the Metropolitan News-Enterprise 2004 Persons of the Year—crossed swords, at least in a manner of speaking, with Van de Kamp getting the fast track ball rolling and Collins trying to make sure it did not roll too far too fast.

Van de Kamp, as attorney general, was the first to push for the legislation which created fast track pilot programs in the state’s busiest courts.

Fast Track Reviewed

Collins served on a committee that reviewed the results of the pilot programs—including vociferous complaints from litigators who felt caught up in them—and molded them into the delay reduction legislation that eventually became applicable to all of the state’s civil courts.

“I am the father of fast track, in a way,” Van de Kamp says, explaining that the impetus for the 1986 pilot programs came from the National Center for State Courts, the sponsor of a meeting Van de Kamp attended in Chicago at which a presentation on delay reduction efforts around the country was made. On his return, he met in San Francisco with members of the Attorney General’s Office staff and suggested California should become involved.

“I said, ‘We really need to get into this,’ Van de Kamp recalls. “The five-year delays in Los Angeles were outrageous. It was a waste of court time and money. There was so much redundancy and cost to clients.”

San Francisco attorney Richard Jacobs of Howard Rice Nemerovski Canady Falk & Rabkin, then a special assistant to Van de Kamp, was given the task of putting together the legislation, which he recalls was carried by then-Assembly Speaker Willie Brown. Though delays in Los Angeles County and elsewhere had become acute, changing the system was then “something the Judicial Council just didn’t want to get involved in at the outset,” Jacobs says.

Jacobs remembers he had just read an article about “active case management techniques” in the federal system. The pilot program was based on those models—“making sure that the judge manages the case rather than leaving it solely to the attorneys,” Jacobs explains.

“The results were quite significant,” the attorney declares. “Cases that were actively managed by judges did, in fact, move faster.”

Collins does not dispute that, but his recollections of the pilot program in Los Angeles have a somewhat different flavor. The program created major headaches in the 25 courtrooms in which it was tried, he says.

“It was from the get-go a real problem,” Collins explains. “John was at the other end of it. He takes credit for bringing it to California and I would never, ever compliment him for that.”

Though the long delays were a genuine crisis to which the pilot program brought attention, the solution of trying to resolve nearly all cases within a year was too extreme, Collins says.

“They set it in motion and it was hell,” Collins recalls. “Sanctions, they jammed you around, they treated you like dirt. We tried to work things out and we weren’t getting anywhere.”

Joint Panel

In 1990, then-Chief Justice Malcolm Lucas and Brown appointed a six-person working group to help an Assembly subcommittee put together a long-term proposal to address the difficulties and incorporate what had been learned in the pilot program, Collins explains. The panel included three trial court judges, then-State Bar President Alan Rothenberg, and the president of the California Trial Lawyers Association as well as Collins, a litigator whose office represents mostly defendants.

Then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Robert H. O’Brien, who has since retired but continues to sit on assignment, was a member of the group and recalls that it worked on such issues as timelines and when Doe defendants would have to be dismissed.

“There was a lot of reluctance from some of the bar at that time and some of the judges that this was just too radical a change at one time,” O’Brien says. “We hacked out the amendments.”

The result was Government Code Sec. 68616, which O’Brien describes as “almost identical” to what the panel unanimously recommended, though there have been minor changes since. The statute specifies that delay reduction rules adopted by the Judicial Council “shall not require shorter time periods” than certain minimums.

“We got all of the relief that we wanted,” Collins says. “We really accomplished a great deal.”

Van de Kamp says the delay reduction rules have generally benefited the courts.

“The judges had just let it go and lost control,” he asserts. “Now the judges really have control of their courtrooms and its worked I think a lot better.”

But he concedes that pressure to resolve cases within specified time frames can sometimes be counterproductive.

“You always need some escape valves,” he says.

For his part, Collins agrees that some reforms were needed. But he remains far from a fast track enthusiast.

“There still are problems,” he argues. “There are some judges who blindly adhere to resolution within 12 months without having any idea what the hell is involved in putting a case together.”

Some kinds of cases—legal malpractice is an example, Collins says—are much more likely to settle without the investment of major court system resources when there is less pressure to meet a deadline, the LACBA president asserts.

“The best thing in legal mal is to let the case kind of meander along and you diffuse the hurt feelings and the anger and the cases will resolve,” Collins says. “If you rush into trial you’re going to have a disaster that could have been avoided. There’s got to be some restraint.”

Praise From MacLaughlin

Los Angeles Superior Court Presiding Judge William A. MacLaughlin has known both Collins and Van de Kamp for a long time. Collins, he notes, “has been so active in so many things over a period of years that you would have to be a recluse not to have come across him within the legal community.”

They first met, he recalls, while working on separate cases for a common client, and later served together on court committees after MacLaughlin became a judge.

“I found John to be not only very easy but also interesting to work with,” MacLaughlin says. “I greatly admired his absolutely wonderful professionalism….I have the highest admiration for how John practices law.”

MacLaughlin and Van de Kamp go even further back, having first met, MacLaughlin relates, when both were doing reserve duty in an Army National Guard JAG unit after law school in the middle 1960s.

MacLaughlin was an officer, but Van de Kamp, the presiding judge recalls, was an enlisted man assigned to clerical duties despite his law degree.

“John was reasonably quiet,” MacLaughlin says. “In the kind of duty that we had that was probably well advised. But there wasn’t any question in my mind that John was going somewhere. There wasn’t any question about John being a person with purpose.”

Addressing their selection as 2004 Persons of the Year by this newspaper, the presiding judge comments:

“I think we’d all be hard pressed to find persons who have contributed more than either of them has.”

Beginnings

In addition to being born at opposite extremes of the year 1936—Van de Kamp in February and Collins in December—the two men started out in life at opposite ends of the Los Angeles basin. Van de Kamp was born in Pasadena and Collins, though born at Queen of Angels Hospital near downtown, went home to Corona del Mar in northern Orange County.

Neither man focused early on a law career.

Though several of Collins’ close relatives, as well as his father, were attorneys, Collins says that as an adolescent he viewed the profession with a jaundiced eye.

“My thought was not to be a lawyer because I saw how stressful and difficult it was for my dad,” he explains.

That thinking changed, he says, when he interviewed with some large corporations during his senior year at the University of Santa Clara.

“All of a sudden it dawned on me that I could never exist in that big corporate atmosphere, and that I’d better do something where I could do it on my own by myself and no one could ever take it away from me—and law school was it,” he recalls.

Van de Kamp was a precocious student whose parents saw to it that he received an unconventional early education. He attended a private boys school in Altadena called Trailfinders, which emphasized outdoor activities like camping and rock climbing as much as academics.

He went off to Dartmouth for his undergraduate studies at age 16, motivated, he explains, by his love of the outdoors and the Hanover, N.H. school’s setting and activity programs. But soon after he arrived he became deeply involved with the campus radio station and wound up spending little time in the woods or on the ski slopes.

While he gave some thought to a broadcasting career, interviewing in New York and spending a summer as a mail clerk at the ABC Television studios on Prospect Avenue in Los Feliz, like Collins he eventually settled on law school as the more prudent choice—concluding, he says, that “from an independence standpoint” he would be better off as a lawyer.

Collins earned his law degree from Loyola in 1961, while Van de Kamp graduated from Stanford Law School in 1959, at age 23. Both soon found themselves working as public servants.

Collins, after a stint as a research attorney for Los Angeles Superior Court Judge A. Curtis Smith in the court’s Appellate Department, signed on as a deputy county counsel—only the 26th lawyer in the then-small office. Smith had been assistant county counsel, Collins notes, adding that partly due to the jurist’s influence he turned down offers from the public defender and district attorney which were also based on his performance on the same qualifying examination.

Van de Kamp was on active duty in the U.S. Army for six months and then in the served in the National Guard following law school. He was appointed an assistant U.S. attorney for the Central District of California in 1960, and served briefly as interim U.S. attorney.

Later he became director of the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys in Washington, D.C. where he coordinated activities between the Justice Department, the Attorney General’s Office, and the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

Experiencing History

“I felt a little bit like Forrest Gump, being around history,” Van de Kamp says of working in the nation’s capital during the late 1960s. He recalls conducting an investigation of black activist Stokely Carmichael when Carmichael was accused of brandishing a gun on a public street.

Van de Kamp says his inquiry showed Carmichael had taken the gun away from someone else.

“He was acting in the public interest, as it turned out,” the former attorney general comments.

Van de Kamp was based in Washington from 1967 until 1970, and in the latter year served on the staff of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest. It was also while working in Washington that Van de Kamp made his first run for elective office, a bid to replace Ed Reinecke in a San Fernando Valley congressional seat when Reinecke became lieutenant governor.

A group of influential Democrats, Van de Kamp remembers, thought the seat might be one the party could capture and encouraged him to make himself available.

“I thought about it as I sat at my desk, and I said, oh, what the hell, I’ll do it,” Van de Kamp recalls. The group supported him, he says, even though he missed most of the meeting it held to interview potential candidates after flying back from Washington and going to the downtown, rather than the Beverly Hills, Hilton.

Though he lost the special election in a runoff to Barry Goldwater Jr., Van de Kamp says the campaign gave him a solid start on a political career.

“It was the best political education I ever had because I had to learn how to work as a candidate—I worked my tail off from sunrise to midnight—and I met a lot of wonderful people,” he declares, adding that the campaign was so far from acrimonious that Goldwater later wrote a letter of recommendation for him when Van de Kamp was under consideration for the directorship of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

“It provided to me the lesson that I have tried to remember, and that is…what goes around comes around,” he observes.

Meanwhile, Collins—after about four years in the County Counsel’s Office—was ready for a change of direction. He recalls that he was offered a job by John P. Pollock, now with Rodi, Pollock, Pettker, Galbraith & Cahill.

Pollock, Collins says, was the first attorney to obtain a million dollar verdict against the county.

But when Collins’ father heard about the offer, he said he would match Pollock’s figure if his son would join his firm. They formed Collins & Collins, the firm Collins has been with ever since.

Father’s Influence

Though James Collins retired in 1976 and died in 1986, his name remains a part of the firm sobriquet, which is now Collins, Collins, Muir and Stewart.

|

|

|

Attending the annual dinner of the Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick in the late 1960s are, from left, attorney Tom Collins, a cousin of John Collins; John Collins' brothers Patrick and Michael Collins; astronaut Michael Collins, no relation; John Collins' father and law partner James E. Collins; and John Collins. |

“His father had a good practice and John had the ability to take off from there,” Pollock comments.

Collins’ partner, Sam Muir, says Collins is “honest to a fault, absolutely loves and adores the legal profession,” adding, “He loves it more than any lawyer I know.”

Though Collins’ practice has been largely on the defense side, he says many of his best friends are plaintiffs’ litigators—often attorneys he first met on opposite sides of the legal barricades. He deplores the tendency to personalize such distinctions, arguing that lawyers are professionals who should be able to represent either side in a dispute with the same kind of professionalism.

In fact, though Collins has long been active in several major defense bar groups, it was his representation of a tort plaintiff over a decade ago that brought him into conflict with a group formed to coordinate the defense of public entities.

Collins, as a favor to a former college classmate, represented a child injured in a South Pasadena park. After winning a jury verdict, he found himself blackballed by the Southern California Joint Powers Insurance Authority.

The group declined to include Collins’ firm on its defense panel, preventing him from working for cities which were SCJPIA members—including one for which he had already handled many cases.

“It is not our practice to include law firms on our defense panel which have been involved in litigation against one of our members,” SCPJIA General Manager William A. Holt wrote to Collins in 1994.

Collins blistered over that position in an article, headlined “I Stepped Over the Line,” in Verdict, the publication of the Association of Southern California Defense Counsel.

“How ironic that in the exercise of my license to practice law I did something that wrongfully disqualifies me from representing a client,” Collins fumed in the article. “The system is out of whack.”

He went on to declare:

“The advocate is no longer allowed to represent the interests of the client—the advocate must bow to the will of the special interest.”

Though he “caught hell” for the penning the article when it appeared, the group eventually backed down, Collins notes.

Bruce A. Broillet of Greene Broillet Panish & Wheeler is one of many members of the plaintiffs’ bar who met Collins as an opponent and counts him as a friend.

“He is a powerful advocate for his clients’ interests and of the highest ethical standards,” Broillet comments. “He has a booming voice and when John Collins talks, people listen.”

Broillet is also one of many who mentions the “hilarious” roast of Collins conducted by the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles in 2001, citing it as an example of the respect and affection with which the plaintiffs’ bar regards their frequent opposite number. CAALA Executive Director Amanda Gazlay notes that while the event, a fundraiser for the group’s public education arm, has on occasion targeted other defense lawyers, “John got on the list because he’s a popular guy among the plaintiffs’ bar.”

It was, she adds, the “funniest roast that we have had in all the years we were doing it,” explaining:

“They roasted him well and he roasted right back when he got up. It was a blast.”

Collins deftly brushes aside any suggestion that his numerous bar group presidencies evidence a remarkable selflessness.

“I’ve always been involved in multiple things,” he shrugs. “It’s part of your obligation. If you aren’t going to help make it better, shut up and go away. That’s the way I look at it.”

While both Collins and Van de Kamp are participatory to a degree that many active, let alone ordinary, lawyers might find incredible, their chosen venues—even though they partly overlap—might be seen as reflecting differences in temperament and orientation.

During his decades in public office, Van de Kamp continued to serve regularly as a LACBA delegate to what was then called the State Bar Conference of Delegates. (It has since been reconstituted as the Conference of Delegates of California Bar Associations.)

‘Difficult Group’

Collins, who was a member of the State Bar Board of Governors when Wilson vetoed the dues bill, in a rare burst of diplomacy describes the conference as a “difficult group.” Wilson’s action was widely seen as retaliation for such conference actions as a resolution condemning the use of the death penalty.

While Wilson had “some legitimate gripes” about the conference and other State Bar activities, the veto was retaliatory, Collins says.

“He was getting even,” the lawyer declares. “Payback is hell.”

But he also has a vivid recollection of listening to the conference debate fast track issues while he and his committee were engaged in drafting the fast track legislation. That debate was unfortunately typical of conference proceedings which too often became mired in dogmatic posturing and contributed little to resolving important issues, he says.

“They didn’t have a clue what the hell was going on,” he asserts. “Not a clue. Here we are negotiating a peace pact and they’re down there beating the hell out of things that were absolutely irrelevant, or absolutely incorrect.”

Van de Kamp returned from his stint in Washington to continue his political activity, working on the unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign of Jesse Unruh against Ronald Reagan in 1970, and on the successful campaign of his friend Ed Miller for San Diego district attorney. But in 1971 his career took an abrupt turn when he was selected by the U.S. District Court’s judges to form the Central District’s Federal Public Defender’s Office.

The Central District office was one of the first Federal Public Defender Offices to be launched on a permanent basis after a series of pilot programs, Van de Kamp recalls. He and others involved in the fledgling operation speak warmly of the camaraderie it engendered.

‘Very Good Office’

“We built a very good office and remained to very close to one another, and it was great fun,” Van de Kamp says. “For many of them it was one of the best things they ever did, and I really enjoyed it.”

Van de Kamp took a one-third caseload, he recalls.

“I took pot luck in the cases that came in. I handled parole revocations at Lompoc and Terminal Island, and so I’d go to those institutions and handle eight to ten cases in the course of a day.”

The transition from the prosecutorial work he had done with the U.S. Attorney’s Office to defense work was not difficult for him, Van de Kamp says. Though he remembers lobbying Congress to re-write the criminal code, and though the federal public defender in those days had a substantial caseload of draft resister prosecutions, the position was “not a political job at all,” he explains.

Barry J. Portman, now the federal public defender in San Francisco, was one of the first to come on board. He remembers it as an “extraordinarily diverse office,” noting that at first the lawyers shared a single office.

“We by necessity had to be collegial—either that or we would have been in fist fights,” he recounts

Portman also recalls Van de Kamp standing up to prosecutors and federal enforcement agents who recalled him as a former colleague and initially expected more cooperation than they got.

“There were a few moments when John had to become the great teacher and the great educator,” Portman remembers.

In 1975, Van de Kamp was selected by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to replace District Attorney Joe Busch, who had died. Though he had applied for the job—the supervisors conducted “sort of an open process” in searching for Busch’s replacement, Van de Kamp recalls—he says his selection took him by surprise.

“It was sort of a rubber duck falling out of the ceiling business,” he comments.

Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Harry Pregerson, who as a member of the court served on the committee that chose Van de Kamp to head the Federal Public Defender’s Office, remembers being part of a lobbying effort on Van de Kamp’s behalf for the district attorney job. He recalls asking a friend who was then a member of Congress to contact then-Supervisor Kenneth Hahn and to urge Hahn to vote for Van de Kamp.

“He’s an outstanding leader, and he’s very thoughtful and very careful and very organized,” Pregerson says of Van de Kamp, adding:

“Before he makes a move he accumulates all the evidence and information he needs.”

The jurist bemoans the fact that Van de Kamp’s bid for governor in the year Wilson was elected was not successful.

“He’d have been a much better governor,” Pregerson says.

Van de Kamp did not get Hahn’s vote for district attorney, but he did get the votes of three other supervisors—and the job.

“I think that what appealed to them was that I was independent of the office,” he says now. “They felt that they needed a new broom, the clean sweep in the office.”

One of his first—and best—decisions as district attorney was to name Stephen S. Trott his chief deputy, Van de Kamp says.

Trott, now a senior judge of the Ninth Circuit, notes that he had himself been among the candidates to head the office, where he had already been working under Busch as a deputy district attorney. That fact did not stop Van de Kamp from making the selection, and Trott recalls that he became the inside man to compliment Van de Kamp’s outsider role.

“John was one of the most outstanding people I have every had the pleasure of working with, and I’ve worked with a lot of good ones,” Trott declares, calling him “a man of total and complete honesty and integrity.”

Trott explains:

“We worked together extremely closely. He’s a brilliant guy when it comes to putting things together.”

The jurist adds that Van de Kamp is an example of someone who “does the right thing for the right reason even when nobody is watching.”

|

|

|

Van de Kamp is seen meeting with President Jimmy Carter in 1977 to discuss his possible appointment as director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Van de Kamp was one of five persons recommended for the post by a presidential panel. Carter bypassed all five, selecting William Webster. |

In 1982, after winning two elections for district attorney, a reshuffling of the state’s top political offices gave Van de Kamp the opportunity to run statewide. With Sen. S.I. Hayakawa retiring and Gov. Jerry Brown opting to run for the Senate, Attorney General George Deukmejian became a candidate to succeed Brown, leaving the state’s top legal post wide open.

Efforts Touted

In the campaign, he touted his efforts as the county’s top prosecutor, citing the creation of child abuse, sexual assault, and officer-involved shootings units, among other initiatives.

Van de Kamp defeated Omer Rains, then a state senator from Ventura County, to win the Democratic nomination. While Deukmejian won the governorship, Van de Kamp defeated George Nicholson, then a senior assistant to Deukmejian and now a Third District Court of Appeal justice, to win the post.

Already being talked about as a potential candidate for governor, he easily won re-election in 1986, defeating a little-known and underfunded Republican opponent.

As attorney general, he staked out strong positions on the environment, consumer protection, offshore drilling, antitrust enforcement, and civil rights, all matters that play well with Democratic activists, while maintaining the high profile on crime that is traditionally associated with the office.

He started the 1990 gubernatorial campaign with strong poll numbers and funding, and won the backing of the state Democratic Party. But Feinstein attacked him with a heavy barrage of advertising, finding vulnerability on the crime issue that, as the state’s number one law enforcement official, he had hoped to claim as his own.

While Van de Kamp noted the large number of death penalty cases handled by the district attorney’s and attorney general’s offices while he headed them, he was blasted for his pronounced personal opposition to the death penalty and his decision as district attorney not to prosecute “Hillside Stranger” suspect Angelo Buono Jr.

At the time, Van de Kamp said he had been assured by the prosecutors who investigated the case that a conviction could not be secured. But then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Ronald M. George, now the state’s chief justice, ruled that dismissal of the case would not be in the interests of justice and ordered that the Attorney General’s Office take over the case.

In November 1983, Buono was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole after being convicted of killing nine young women. He died in prison in 2002.

Van de Kamp also found himself on the defensive over the continuing conflict between the role of the attorney general as a political leader and policymaker and that of chief lawyer for the state.

Feinstein sought, apparently successfully, to cut into Van de Kamp’s liberal base by noting that as attorney general he had defended Deukmejian’s decision to cut the funding of the state Office of Family Planning and had argued for the constitutionality of state budgets that did not fund Medi-Cal abortions for poor women—a stance Van de Kamp had reversed in 1988.

He also defended a law, declared unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court after he left office, that prohibited minors from obtaining abortions without parental consent or judicial approval.

After losing the primary to Feinstein, he completed his term as attorney general in January 1991. While he did not rule out another candidacy at the time, he never again sought election to public office, concentrating on his practice in the Los Angeles office of the New York-based Dewey Ballentine firm and his efforts on behalf of racehorse owners, who made him president and general counsel of the Thoroughbred Owners of California and a director of the National Thoroughbred Racing Association.

Board Seat

He ran for the State Bar Board of Governors in 2001, winning without opposition, a seat representing District 7—Los Angeles County—and was elected to the organization’s presidency last year. George swore him into office.

Van de Kamp says he harbors no bitterness about losing the opportunity to run against Wilson. He declines to speculate about how that race might have come out, and says he thinks two terms as attorney general were enough.

“I’ve watched too many other friends of mine who’ve been in public office—sheriff’s offices, D.A.’s offices—who’ve been there too long and have lost the freshness that you really need to bring to that office,” he comments. “Things tend to get ingrained, allegiances tend to harden. It’s sort of a natural term limitation that I put in, in the way that I behaved running for higher office.”

Feinstein was a tough campaigner—“Dianne obviously was good on her feet, and has been an effective elected representative,” the State Bar president concedes—and as a woman candidate her time, he says, may have been at hand. Wilson, too, he acknowledges, was a formidable politician who “clearly would have gone after me—even though I prosecuted death penalty cases, I was against the death penalty—and made me out to be a liberal.”

But he also points out that his bid for governor became bogged down in the fight over three ballot initiatives addressing environmental concerns, campaign and governmental ethics reform, and crime. While his supporters had hoped the initiatives would help build support in a general election battle with Wilson, instead they sapped resources he wound up needing in the primary campaign against Feinstein.

None of the initiatives passed, and while Van de Kamp notes that most of the reforms included in the environmental measure, dubbed “Big Green,” eventually became law, they also helped to unite a variety of business and other interests against him.

Van de Kamp recalls:

“We threw everything but the kitchen sink in, and so we had various interest groups attacking it, and people said, ‘It’s too confusing, I don’t understand it.’ People were throwing up their hands.”

Seen as Electable

Barbara Yanow Johnson, who worked for Van de Kamp when he was district attorney and attorney general, managed most of his electoral campaigns, and chaired his gubernatorial campaign committee, says she has no doubt that he could have beaten Wilson.

Johnson, who is married to Justice Earl Johnson Jr. of this district’s Court of Appeal, Div. Seven, and now has a practice serving as an independent factfinder in workplace discrimination disputes, declares:

“I have no doubt that had he won the primary he would have won the general election….He had the record.”

Instead, she says, Van de Kamp ran into the “phenomenon of Dianne Feinstein,” an “extraordinary woman” whose assumption of the San Francisco mayoralty in the wake of the assassinations of then-Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk gave her a “compelling story to tell.”

She describes Van de Kamp as “a very thoughtful and reserved person” who was “certainly…happier serving in elective office” than running for it—unlike many other politicians, she suggests.

“No one worked harder as a campaigner,” she observes, but she adds that Feinstein’s “initial ads about the assassination were incredibly powerful, and they overwhelmed the primary.”

Van de Kamp is married to Andrea L. Van de Kamp, chairman for Sotheby’s West Coast and long a force on Los Angeles’ cultural scene. She served as director of development for the Museum of Contemporary Art when it built its current home on Grand Avenue, and was chair of the Music Center board when the effort to raise the funds needed to complete the Disney Hall was launched in 1996.

In 2003 she was named the Music Center’s first chairman emeritus. The Van de Kamps’ daughter Diana, who is 25, manages fledgling rock groups and develops computer programs which deliver educational content over the Internet.

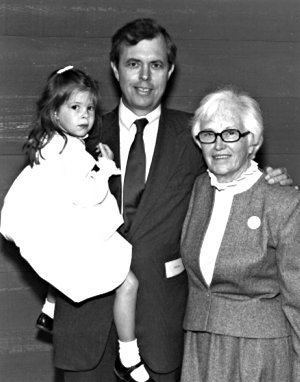

|

|

|

Van de Kamp poses with daughter, Diana, and mother, Georgie Van de Kamp, in 1982. |

Portman notes that, while attorney general, Van de Kamp stood by an assistant accused by a friend’s daughter of improper sexual conduct. Believing the man had been falsely accused—he was later vindicated, Portman says—Van de Kamp “stood by him when it was certainly no political benefit and in fact a considerable political detriment to do so,” the federal public defender declares.

“You just don’t see people with political ambitions be stand up guys like that,” Portman comments, adding:

“There is a streak of integrity and loyalty in John that you rarely see in public figures. He is the model of a public servant.”

Personal Loss

Several colleagues note that Collins has maintained his grueling schedule of litigation and bar activities through a trying period brought on by the illness and death of his daughter Andi, who lost a battle with a rare form of cancer in September 2003 at age 16.

Attorney Robert Baker of Baker Keener & Nahra, says:

“He’s an amazing human being….There are few people in life who in the face of complete adversity maintain a positive outlook. Those are the type of people that lead the world.”

Collins has had eight children, the product of two marriages. Two are now undergraduate students at the University of Southern California who, Collins reports, say they plan to attend law school.

His son Will Collins entered USC without an atheletic scholarship but later earned one and became the long snapper on this year’s USC national champion football team.

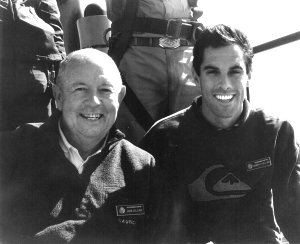

|

|

|

John J. Collins is seen with son, Will Collins, at USC game. |

Collins was elected to the Board of Governors in 1996, also as a District 7 representative. He was eligible to run for the presidency in 1999 but chose not to.

The veteran litigator decries the lack of civility in the practice of law in today’s legal field.

“I certainly don’t buy the approach that seems to be adopted by so many about a lack of civility….It’s just way out of control,” Collins says.

“This civility thing isn’t just between lawyers,” he says. “It’s among the whole triangle of court and counsel on both sides.”

Former State Bar President Tom Stolpman of Stolpman Krissman Elber & Silver in Long Beach echoes Collins’ concerns about civility in the profession.

“Everybody now thinks it’s a battle instead of a dispute resolution process,” Stolpman says, adding that the process of litigation “should not necessarily be one in which lawyers learn to hate each other.”

Collins’ involvement with ABOTA has helped that group in its efforts to ameliorate the growing problem, Stolpman says, calling Collins a “lawyer who exemplifies the best of our profession.”

He adds:

“What he brings to the law is a very positive thing.”

Future Plans

In the remainder of his term as LACBA president, Collins says, he plans to work to make sure that the organization’s basic missions—services in immigration law and to victims of domestic abuse and efforts to provide legal services to the poor—are maintained. Some other plans, he points out, had to take a back seat to finding a new executive director for LACBA when long-time leader Rich Walch resigned last year.

Stuart Forsyth, a former senior manager with the State Bar of California and the former head of the State Bar of Arizona, has replaced Walch.

“He’s a talent, and he’s very well respected, and I think he’s going to do great things here,” Collins comments.

In addition, Collins hopes to address a number of issues involving the operations of the Los Angeles Superior Court by reviving a LACBA Blue Ribbon Commission on Superior Court Improvement which issued its final report in 2000.

That panel, which he chaired, “really took a look at how the court delivered services,” Collins says, but he asserts that a number of its recommendations have “yet to be fulfilled.”

One topic he intends to revisit, he says, is Superior Court governance.

“That was and that is even more of a problem today, because the local courts do not have effective power to control the independent constitutional officers, who seem to think that some of them can do as they damn please,” Collins declares. “So we’re going to take a look at what is available, what we might accomplish on a statewide basis, and I think we’re going to be working at this more with the [Judicial] Council. We’re going to reconstitute [the Blue Ribbon Commssion] with some new players, and I’m going to chair it.”

While the panel that issued the 2000 report included two USC professors, and its work was funded by a grant from the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation, the new panel will “stay strictly with trial types,” Collins says.

He suggests that the current governance structure gives the court’s administration little power to influence the behavior of judges. The court’s presiding judge is chosen by his colleagues for a two-year term, Collins points out, meaning he or she will shortly find himself once again working side by side with the judges under his or her supervision.

“And you might be right next door to the man or woman that you were telling to straighten up and fly right,” he says. “So what can you really do? I think it’s got to be on a statewide level.”

The Commission on Judicial Performance, while it has the power to discipline judges, generally does so only after lengthy proceedings, Collins notes.

“Maybe it’s the A[dministrative] O[ffice of the] C[ourts], maybe it’s the [Judicial] Council, but there’s got to be some agency, because I don’t think CJP gets to it quick enough,” Collins declares.

Part of the problem, he suggests, may be that some of the best judges leave the bench because they can make more money in private dispute resolution.

“I think it’s laughable when I look at what we pay new lawyers and compare that to what we’re paying sitting judges,” Collins comments. “It ain’t right.”

While Collins is frank enough to say the Los Angeles Superior Court has problem judges—“There are some judges that have just raised hell with lawyers,” he says—he is not about to name them publicly. But neither, when asked to do so, does he beat around the bush.

His response is direct and to the point, if unenlightening:

“Next question.”

While Collins sounds like he may be planning to raise a little hell with the court system before he leaves office as LACBA president in July, Van de Kamp, in contrast, makes it clear that he does not see the State Bar presidency as a platform for making waves.

Van de Kamp’s term will be a short one as a result of the vagaries of State Bar convention scheduling.

State Bar presidents hold office from one annual meeting to the next. Last year’s meeting was in Monterey in October, while this year’s will be held in San Diego in September.

But his view of his role as president, Van de Kamp says, is deeply colored by the fact that the Board of Governors has just completed a lengthy strategic planning process which resulted in a voluminous set of goals and objectives.

Discipline Concerns

“My obligation is to make sure that we address those,” Van de Kamp says.

Some, like strengthening the discipline system by developing ways to deal with lawyers who have problems before suspension or disbarment becomes necessary and tweaking the admissions process, are really a part of an ongoing process, he says. Others, like establishing a “member center” which can serve as a consolidated resource for information and lawyer benefits, have long been discussed.

One way in which he can contribute, Van de Kamp says, is to facilitate more participation by big firm lawyers in the State Bar. While such attorneys once dominated the organization, in recent years the pendulum has swung too far the other way, he suggests.

“The old line leaders of the bar came from those firms. More and more, it’s just gone the opposite direction, and clearly what you need on the board of governors is a balance…I hope that I can stimulate interest in the Board of Governors as I get around the state.”

His years with Dewey Ballantine since leaving public office position him well to reach that audience, Van de Kamp says.

“I have a pretty good understanding of how big firms operate,” he adds. “I certainly understand the billable hours syndrome, and the problems associates go through, and the efforts that are being made by big firms to diversify, which are substantial in most big firms that have a conscience about what they are doing. And you learn a lot about the economics of law practice that I certainly did not run into with 30 years of public life.”

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company