Tuesday, August 16, 2005

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

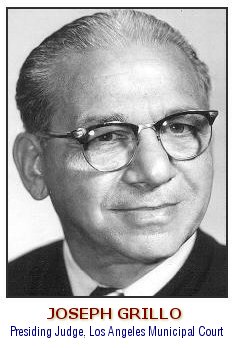

1976: LACBA Censures Judge Grillo for Abusing Powers

By ROGER M. GRACE

Joseph Grillo was presiding judge of the Los Angeles Municipal Court. The Los Angeles County Bar Assn. on Oct. 14, 1976 censured Grillo and determined that it would call upon the Commission on Judicial Qualifications (now known as the Commission on Judicial Performance) to investigate his conduct.

The

conduct in question had occurred on Friday, Aug. 6. Grillo wanted the county

(which provided major finances to the court) to supply two round-trip airplane

tickets, each worth $53. They were to be used by Grillo  and Judge James Di

Giuseppe in going to Sacramento

the following Monday to lobby for favorable committee action on a bill that

would have created six additional judgeships on the court. The Board of

Supervisors opposed the bill, and Transportation Manager James Czarnecki was

under orders from Chief Administrative Officer Harry Hufford and Auditor Mark

Bloodgood not to issue the tickets. Accompanied by his bailiff, his

administrative assistant, and the court’s chief administrative officer, Grillo

marched across the mall to the Hall of Administration and presented a court

order to Czarnecki to hand over two tickets. When they weren’t proffered, the

judge had the transportation manager arrested and taken to Div. One, where he

found Czarnecki in direct contempt, and sentenced him to two days in jail.

and Judge James Di

Giuseppe in going to Sacramento

the following Monday to lobby for favorable committee action on a bill that

would have created six additional judgeships on the court. The Board of

Supervisors opposed the bill, and Transportation Manager James Czarnecki was

under orders from Chief Administrative Officer Harry Hufford and Auditor Mark

Bloodgood not to issue the tickets. Accompanied by his bailiff, his

administrative assistant, and the court’s chief administrative officer, Grillo

marched across the mall to the Hall of Administration and presented a court

order to Czarnecki to hand over two tickets. When they weren’t proffered, the

judge had the transportation manager arrested and taken to Div. One, where he

found Czarnecki in direct contempt, and sentenced him to two days in jail.

The judge stayed imposition of sentence until the following Wednesday to permit time for an appeal, explaining that “part of being a judge is compassion.”

County Counsel John Larson—who burst into Grillo’s chambers after the incident and shouted profanities at the judge—had a petition for writ of habeas corpus prepared. However, on Tuesday, shortly before the matter was slated to be heard before the Appellate Department of the Superior Court, Grillo rescinded the contempt order.

![]()

Lawrence Crispo, then a young lawyer (later a Superior Court judge and now a private judge) was chair of the County Bar’s Judiciary Committee. He referred the incident to a four-person subcommittee comprised of William A. Masterson (later a justice of this district’s Court of Appeal, now retired), Douglas Dalton, Phyllis Hix and Howard L. Weitzman.

The subcommittee interviewed Grillo, Czarnecki, and others and produced a 22-page report. The conclusion which the subcommittee reached was that “Grillo’s activities were an abuse of judicial power.”

The four attorneys declared: “Our review of the applicable law and statutes fails to disclose any precedent or justification for Judge Grillo’s action.”

They added:

“Action such as this undertaken by Judge Grillo is more in accord with the procedures of totalitarian regimes than the proper functioning of law in a free society.”

The full committee, comprised of about 30 lawyers, approved the report unanimously. The Board of Trustees unanimously adopted the recommendation to urge action by the Commission on Judicial Qualifications.

There was lack of unanimity, however, with respect to the censure. The Los Angeles Times disclosed:

“The vote for censure reportedly was 11 to 8. The votes, if any, of the other four members were not accounted for.”

There was also said to have been a division of opinion as to whether the report should be made public.

Grillo appeared a few days later at a “Judge’s Night” meeting of the Wilshire Bar Assn. He was slated to speak for about five minutes on the workings of his court. Instead, Crispo told me, he used the time to slam the County Bar for what he portrayed as an inappropriate action against him.

If a judge committed similar misconduct today, would he or she likely be socked with a County Bar censure? Or has the County Bar—which in 1932 steered a successful campaign for the recall of three Los Angeles Superior Court judges—become docile?

![]()

The Commission on Judicial Qualifications did institute disciplinary proceedings against Grillo, and hearings before special masters were held (in secrecy, under the rules at the time) on May 10, 11, 12 and 16, 1977. On May 16, Grillo filed an application for a disability retirement. He had been on sick leave since Jan. 4.

The application was approved by the commission on Aug. 12, 1977, but it was subject to review by the chief justice, Rose Bird. She kicked the matter back to commission, saying that she wanted the disciplinary case resolved first. The commission said “no,” bouncing the application right back to Bird. It pointed out that a California Supreme Court case said that once a medical disability is found, the commission must grant a retirement request and end any disciplinary proceedings. On Nov. 22, 1977, the chief justice signed Grillo’s “certificate of retirement.”

Grillo died in 1993 in Reno, Nev., where he was residing.

![]()

![]()

![]()

IN OTHER ACTIONS...: Through the years, these stances have been taken:

•October, 1931: Disapproval was expressed by the association of the radio broadcast of a particular trial that was in progress, or any other trial. Six years later, it denounced the taking of news photographs at court sessions, and the following year, castigated Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Ingall Bull for allowing photographers in his courtroom. In the years ahead, the County Bar and the press were frequently at loggerheads. I’ve previously mentioned the association’s success in obtaining contempt proceedings against the Los Angeles Record and the Los Angeles Times. In doing battle with the latter, the upshot was a repudiation by the U.S. Supreme Court of the County Bar’s premise that public comment on pending proceedings was contemptuous if there was a chance it would affect proceedings.

•November, 1934: The association launched an investigation of conduct on the part of a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, Guy Bush. On April 10 of that year, Bush had acted to reduce to six months the two-year sentence he previously imposed on a man who had been found guilty of grand theft and securities violations. That same day, the convict’s wife filed suit for divorce. And on Oct. 20, Bush married the woman in Tijuana. The judge resigned about two weeks after the County Bar started looking into the matter.

•April, 1945: The Board of Trustees passed a resolution proclaiming that “the policy of the Association expressed in its constitution and in its past history is such that in the absence of a mandate from the membership to the contrary it has no other course than to deny members of the Negro race membership in the Association.” There were those who thought that there very well should be such a mandate. A proposed amendment to the organization’s constitution (which, contrary to the April, 1945 resolution did not expressly bar membership by blacks) said: “Neither race, color, creed nor national ancestry shall be a bar to membership.” (Gender was not mentioned because women had long been admitted—white ones, that is.) There were 604 members voting for the proposed amendment but 768 voting against it. It was not until Jan. 16, 1950 that a count of another round of ballots showed that the membership, by 1,018-593, approved integrating the organization.

•August, 1959: The County Bar persuaded the Board of Supervisors to remove a bust of Abraham Lincoln from a corridor of the new Central Courthouse. The 300-lb. bust was sculpted by Dr. Emil Seletz, a Beverly Hills brain surgeon. Seletz occasionally appeared in the courthouse as an expert witness. If jurors saw Seletz’s name on the bust and then saw him on the stand, well, this could affect the weight they would give his testimony...or so the theory went. A LACBA vice president (and later president), Grant Cooper, was quoted by Associated Press as saying: “It’s just one of those things that interfered with the administration of justice.”

•April, 1960: The LACBA Board of Trustees voted to ask the State Bar to promulgate a rule barring lawyers from appearing on television programs featuring simulations of court proceedings. See the “Perspectives” column of May 16, 2003, at:

http://www.metnews.com/articles/perspectives051603.htm.

•November, 1969: Seth Hufstedler was president of the County Bar (and was later to serve as State Bar president). He charged that criticism leveled at Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Jerry Pacht was “intemperate, inaccurate and unwarranted.” Pacht had ruled that Communist Angela Davis could retain her teaching post at UCLA. Assemblyman Floyd Wakefield of Huntington Park had termed Pacht “incompetent” and announced an effort would be launched to recall him. Hufstedler (now of Morrison & Foerster) said at the time that the County Bar had a duty to “support a judge against such unjust criticism.”

•October, 1971: Stuart Kadison called a press conference to speak on behalf of LACBA, which he headed, in bemoaning the “unwarranted calumny and abuse” heaped on Court of Appeal Justice Mildred L. Lillie in connection with her possible nomination by President Richard Nixon to the U.S. Supreme Court. (There had never been a woman on the high court at that point, and to many, that was just fine.) Kadison pointed to the banner headline on a street edition of the Los Angeles Times which read, “Justice Lillie Not Fit, Bar Unit Says,” with reference to an evaluation by a committee of the American Bar Assn. Kadison said of Lillie: “Her skill as an appellate justice and demeanor and conduct both on and off the bench have been exemplary and completely beyond reproach.”

•October, 1973: LACBA’s president, G. William Shea, lashed out at Nixon for firing Archibald Cox as Watergate special prosecutor. “The president promised an independent investigation of the Watergate matter,” Shea said, “and that means hands off the special prosecutor.” Shea added: “I have conferred with my fellow officers in the Los Angeles County Bar Association and we believe Mr. Nixon should rethink his action and reinstate the prosecutorial team.” Nixon did not heed Shea’s advice.

•March, 1977: County Bar President Jack Quinn (now of Arnold & Porter) said that “petty politicians and headline seekers” had made judges the “proverbial whipping boy.” He declared that lawyers “no longer intend to be timid” in defending members of the bench against unjustified charges.

•April, 1990: A general membership meeting was held, attended by about 625 of the roughly 26,000 members, to consider whether the Board of Trustees had acted properly in voting to put the organization on record as favoring a woman’s right to an abortion. After nearly two hours of debate, the members voted 2-1 in support of a resolution backing the board’s action. Among those arguing was former president Larry Feldman, who asserted: “‘If you are against this resolution and what the trustees are doing, then you vote for mediocrity—you vote for the status quo.” Another ex-LACBA president, Richard Coleman, was among those who had resigned from the organization in protest to its stand.

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company