Tuesday, August 9, 2005

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column):

1964: LACBA Censures Two Judges for Seeking DA’s Post Without Resigning

By ROGER M. GRACE

With the feistiness that characterized the organization in the 1930s, the Los Angeles County Bar Assn. in 1964 censured two Los Angeles Superior Court judges based on their running for district attorney without resigning their judgeships.

Twelve years later, the association censured the presiding judge of the Los Angeles Municipal Court for causing the arrest of a county employee who refused to supply plane tickets to the judge and a colleague in connection with a trip to Sacramento.

Discussion of the 1976 controversy over the presiding judge’s unconventional action is reserved for next week. Here follows a recitation of the County Bar’s tiff with the two candidates for district attorney.

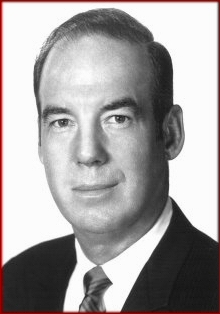

EVELLE J. YOUNGER was on the receiving end of a censure on Feb. 6, 1964 because he ran for district attorney while a sitting judge. That ran afoul of a resolution adopted by the County Bar in 1958.

That resolution was commonly viewed as a rebuke of Stanley Mosk for seeking the post of state attorney general while a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court, though the resolution did not mention Mosk by name. It said:

“It is improper for a judge to become a candidate for election to a non-judicial office without first resigning his judicial position....”

Mosk had, in fact, taken a leave of absence while running for the non-judicial post—a step now required by the state Constitution (Art. VI, §18), though it wasn’t then. (Mosk was elected and went on to serve as a justice of the California Supreme Court from 1964-2001.)

The County Bar’s 1958 president was E. Avery Crary (later a U.S. District Court judge). He publicly declared that the obligation of a judge to resign before running for a nonjudicial office was set forth in “canons of judicial ethics of both the American Bar Association and the Conference of California Judges.” However, both sets of canons, while lent deference, were non-binding on California judges.

LACBA served notice at the time that the association would “condemn publicly any such future political activities of judges.”

![]()

The group was true to its word. It publicly denounced Younger for seeking election as district attorney in 1964 without hanging up his robe. What was puzzling, however, was that while Younger was censured, no mention was made then of another Los Angeles Superior Court judge who was also in the race for district attorney.

Commenting on the censure of Younger, the County Bar’s president, Maynard Toll, said:

“[W]e feel that failure to resign permits the use of the power and prestige of a judicial position to promote the judge’s candidacy for political office.”

He went to say:

“The association’s policy holds that the resignation of Judge Younger is essential to maintaining the independence and impartiality of the judiciary and the establishment of a standard of conduct for members of the bench and bar that will earn public confidence in the existence of such independence and impartiality.”

Since Younger’s resignation was essential (according to Toll) to preserving “independence and impartiality of the judiciary,” and given that he did not resign, it must be assumed that “independence and impartiality of the judiciary” crumbled to dust in 1964.

![]()

Younger responded the day following the censure that the County Bar’s stance was “in conflict with the Constitution of California which permits Municipal and Superior Court judges to run for office without resigning.”

At the time, Art. VI, §18 of the state Constitution provided that “a judge of the superior court or of a municipal court shall be eligible to election or appointment to a public office” during his or her term of office as a judge.

The fact of the matter is that the County Bar censured Younger based not on a violation of law by him, but because he declined to embrace an ethical precept contained in a County Bar resolution.

Younger charged that members of the County Bar’s Board of Trustees, which took the action on LACBA’s behalf, were “out of touch with reality and with most of the attorneys of the county.”

|

|

|

|

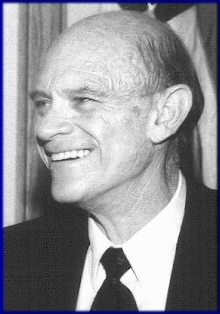

VINCENT S. DALSIMER was the other Los Angeles Superior Court judge in the race. Toll wrote to him in late February threatening reprisals by the County Bar if he did not resign within three days. Dalsimer—who was not one to be intimidated—shot back a letter in which he said:

“I was shocked and surprised to [be told to] resign within three days from the office to which I have been elected by Los Angeles County voters or to suffer a public attack by you on my ethical standards.”

Dalsimer, who was on a voluntarily assumed leave of absence from the court, said:

“I stepped down from the bench so that there would be absolutely no question of my using my judicial prestige to aid in my campaign. Since your apparent position now is that I forever forfeit any right to hold judicial office I can only conclude that your primary concern is not with ethics but with a desire to injure the two judges who are candidates in order to enhance the campaign of your fellow lawyer, Manley J. Bowler.”

(Do you suppose Dalsimer really believed that the motivation was to boost Bowler’s chances because he was a lawyer, not a judge?)

Dalsimer also charged that LACBA’s Board of Trustees was “endorsing Bowler’s candidacy by failing to consider his ethics.” The jurist argued that if anyone should resign from office while running for district attorney, it should be Bowler, who was chief deputy district attorney. Dalsimer explained that Bowler has “much more power than Younger who sits daily in court and infinitely more power than I do while on unpaid leave.”

I don’t quite follow that reasoning, but I also had difficulty grasping reasoning in some of Dalsimer’s opinions as a justice of the Court of Appeal (1981-85).

![]()

The County Bar censured Dalsimer on March 3, 1964. Toll commented that LACBA had urged Dalsimer to “set an example by resigning...before campaigning further for election to the position of district attorney.”

The same day, the demand for the resignations of Younger and Dalsimer was echoed at a press conference by District Attorney William B. McKesson, who happened to be supporting his chief deputy, Bowler. With respect to Dalsimer’s sabbatical, he scoffed that there was no provision in California law for a judge taking a leave of absence except for military service.

As it turned out, there was no mechanism for the county to withhold payments. Dalsimer garnered publicity on April 16 by proffering a check to the Board of Supervisors for $688.45, representing the county’s share of his monthly paycheck. He said he had returned the state’s share by separate check.

![]()

Aside from the County Bar issuing censures, five former presidents of the group took a public stance in connection with what they saw as a separate ethical impropriety surrounding the contest. Led by Joseph Ball, who had also been president of the State Bar (and would later serve as counsel to the Warren Commission), they scored the action of the Los Angeles County Democratic Central Committee in urging Dalsimer in November, 1963, to become a candidate.

Ball said that the call for Dalsimer to run was “ill advised in that it attempts to circumvent the deliberate intent [of the state Constitution] of making this office nonpartisan.”

That stance was ill advised in that it attempted to circumvent the deliberate intent of the federal Constitution, as well as our state Constitution, to protect free speech.

Joining Ball in voicing his complaint were past presidents Walter Ely (later a judge of the Ninth U.S. Court of Appeals), Herman F. Selvin, Hugh W. Darling, and August F. Mack Jr.

A committee to draft Dalsimer was comprised of Democratic Party loyalists. Its treasurer was Harry T. Shafer (who later became a Superior Court judge and joined with Dalsimer and businessman Ed Di Loreto in purchasing a failing Orange County law school, building it up, and giving it to Pepperdine University).

Dalsimer’s campaign markedly was a politically partisan one. Yet, a poll released in March, 1964 showed that, with two-thirds of the voters undecided, Younger, a Republican, had more Democratic support than Republican, and Dalsimer’s support was equally divided between the two parties.

Dalsimer came in third in the primary.

Younger prevailed in the general election, won a second term, and was elected to two terms as attorney general. In 1978, he was the unsuccessful Republican nominee for governor.

Younger, Dalsimer and Bowler are now deceased, as are all of the others mentioned above.

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company