Tuesday, July 12, 2005

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

1970s: LACBA Ends Plebiscites, Stops Endorsing Candidates

By ROGER M. GRACE

The last Los Angeles County Bar Assn. plebiscite in connection with judicial contests took place in 1972, 52 years after the first one occurred. By 1972, the County Bar, which earlier had taken considerable pride in its process, had soured on it. That stemmed largely from the outcome of the election in 1970 in which voters turned out of office Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Alfred Gitelson, who had been staunchly supported by the County Bar.

Gitelson drew ire—even an aborted assassination plot—based on his 103-page decision ordering the Los Angeles City School District to achieve racial balance in local schools by September, 1971. Although the order did not mention busing, it was widely perceived by the public, as well as the school district, as necessarily entailing forced busing as the only practical means of reaching the result. The school district, which appealed the judgment, proclaimed that 200,000 students would be affected.

LACBA sent ballots prior to the June 2 primary election to all of the county’s lawyers and judges. Less than half returned them. Of those who did, 3,311 voted for Gitelson, 780 for Playa del Rey attorney William Kennedy, with other votes spread among attorneys J. Wallace McKnight of Woodland Hills, Dino Fulgoni of Los Angeles (later a Superior Court judge), and Ernest Duncan of Alhambra.

Gitelson’s showing in the plebiscite entitled him, under LACBA rules, to the association’s endorsement. That endorsement, however, was hardly enough to prevent a run-off with Kennedy, an obscure lawyer whose backers could only have predicated their support of him on the fact that he was opposing the “busing judge.”

The incumbent did not fare at all badly in the primary, given that he had four opponents. He bagged 44.08 percent of the vote, with 615,672 ballots cast for him, and Kennedy attained 19.19 percent, or 268,046 votes.

On Oct. 15, as the run-off approached, LACBA President Sharp Whitmore (since deceased) publicly reiterated the group’s endorsement of Gitelson, explaining that it reflected a concern “for the preservation of our system of justice in these times of violence and uncertainty.”

This ad appeared in newspapers on Nov. 1, the Sunday preceding the election:

In

the Nov. 3 general election, all the anti-busing sentiment that had manifested

itself in the primary, and then some, coalesced, resulting in Gitelson, 64, a

13-year veteran of the bench, attaining only 44 percent of the vote. He

received 815,530 votes; Kennedy, 48, got 1,020,963.

In

the Nov. 3 general election, all the anti-busing sentiment that had manifested

itself in the primary, and then some, coalesced, resulting in Gitelson, 64, a

13-year veteran of the bench, attaining only 44 percent of the vote. He

received 815,530 votes; Kennedy, 48, got 1,020,963.

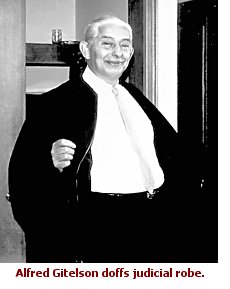

At left is a photo I took of Gitelson, in chambers, on his final day of office, as he removed his judicial robe for the last time:

Gitelson died in 1975.

![]()

Following the election of Kennedy, LACBA issued a statement signed by Whitmore and LACBA President-Elect Stuart Kadison (also now deceased) which, by necessary inference, constituted an utterance of “phooey!” as to the outcome of the election. It said, in part:

“[O]ur state system involves the right of the public to determine, in a public election, who among our incumbent judges should be continued in office.

“If our system is to work properly, this right of the public should be exercised with a realization of the responsibilities that accompany it.

“Some judges, fearful of not being returned to office, could be motivated to decide cases on bases other than those required by the law and the facts. Some judges may be reluctant to decide unpopular or emotion charged cases on the law and the facts for fear of jeopardizing their places on the bench.”

![]()

On “The President’s Page” in the February, 1971 issue of the Los Angeles Bar Bulletin, Whitmore reflected:

“In connection with the primary and general election in 1970 the Association conducted a plebiscite, held a press conference to publicize the results, mailed the results to the news media and sent a letter to each member of the Association urging membership activity on behalf of the single candidate endorsed. That candidate was defeated.”

Whitmore noted that the cost to the County Bar of conducting the 1970 plebiscite “was well over $3,000, without including the lawyer and staff time devoted to it,” yet news coverage of the results was scant.

Taking an overall view, he lamented that “[t]here has been no close correlation between plebiscite results and the way the public votes.”

Indeed, two years earlier, voters had spurned LACBA’s call for the election of attorney Malcolm Mackey to the Los Angeles Municipal Court rather than reelecting the unconventional Noel Cannon. Two years before that, the electorate ignored the group’s urging that Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge George Dell be chosen over incumbent Thomas Yager in a Superior Court race.

Through the years, starting in 1920, the electorate did vote in accordance with County Bar recommendations most of the time. But most of the races were not hotly contested, and where they were, the bar association’s success rate was low.

![]()

LACBA’s Committee on Judicial Appointments in December 1975 submitted a report to the Board of Trustees. Finding that the plebiscites had not had an appreciable impact on the outcome of judicial contests, it urged experimentation with two other approaches: judicial evaluations by committee and the taking of polls. It recommended that a committee be set up to evaluate judicial candidates in the 1976 primary election, and that another committee be established to conduct a poll with respect to Superior Court judges who were up for election in 1978.

The Special Committee on Judicial Evaluation on May 12, 1976 submitted a report to the Board of Trustees in which it rated candidates for five Superior Court offices. The report was signed by the chairman of the committee, Leonard Janofsky (now deceased) of Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker, a former president of LACBA and of the State Bar, who was later to become president of the American Bar Assn. Committee members included a future presiding judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court, Victor Chavez, and a future member of the Court of Appeal, William Masterson.

Here were the evaluations of Superior Court candidates that first year:

Office No.1: EMIL GUMPERT, Incumbent, Judge of the Superior Court, Well Qualified; S. S. SCHWARTZ, Attorney at Law, Qualified; ELANA SULLIVAN, Workers’ Compensation Judge, Qualified.

Office No.2: LAURENCE J. RITTENBAND, Incumbent, Judge of the Superior Court, Well Qualified; ARTHUR STANLEY KATZ, Attorney at Law, Qualified.

Office No. 15: ELISABETH EBERHARD ZEIGLER, Incumbent, Judge of the Superior Court, Qualified; AARON H. STOVITZ, Deputy District Attorney, Qualified.

Office No. 28: ROBERTA RALPH, Attorney/Law Instructor, Well Qualified; WILLIAM P. KENNEDY, Incumbent, Judge of the Superior Court, Not Qualified; BYRON Y. APPLETON, Attorney and Arbitrator, Not Qualified.

Office No. 40: ROBERT M. TAKASUGI, Incumbent, Judge of the Superior Court, Well Qualified; NATHAN AXEL, Judge of the Municipal Court, Not Qualified; DAVID J. AISENSON, Judge of the Municipal Court, Qualified.

The report explained the “not qualified” rating of Kennedy, the man who had replaced Gitelson, by saying:

“[T]he Committee evaluated him as ‘Not Qualified’ because he is seriously lacking in industry and diligence. Further, the Committee was informed by many attorneys and judges that he often takes the Bench late and adjourns court early and does not carry a full work load.”

The County Bar was now only evaluating, not endorsing. Nonetheless, inherent in the report was the direction to voters: retain Gumpert, dump Kennedy.

Both Gumpert and Kennedy lost. Why Gumpert? The issue against him raised by Schwartz in the primary and the general election was his age, 81.

The denunciation of Kennedy by the County Bar committee could well have been instrumental in bringing about his defeat.

Takasugi neither won nor lost the contest. He drew 45 percent of the vote in the June 8 primary—which was quite a feat given that he no longer qualified, having been recently nominated to and confirmed as a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. In August, 1978, Takasugi joined with Aisenson, who had attained 37 percent of the vote in the primary, in bringing an action to have Takasugi’s name removed from the Nov. 2 general election ballot. The upshot was that Aisenson and Axel faced off in the general election and Aisenson won—proving to be a disaster as a Superior Court judge.

The reaction to the committee’s work in the rating of Superior Court candidates in the primary was favorable and the committee proceeded to rate the 10 candidates in the Municipal Court races on the November ballots (including one candidate who was dead).

In his “The President’s Page” message in the January, 1977 issue of the Los Angeles Bar Bulletin, Jack Quinn commented that the “Committee’s efforts have been widely heralded as one of the most comprehensive and constructive ever performed in connection with judicial elections and of which the Association can and should take great pride.”

In light of general satisfaction with the new approach, no experiment took place in 1978 with a “poll.” The method inaugurated in 1976 has endured, although the thoroughness of the explanations of “not qualified” ratings, regrettably, has not.

![]()

LACBA’s immediate past president, John J. Collins, told me the association “does a super job” of evaluating candidates. “Where we fail,” he acknowledged, “is getting our ratings out to the public in general.”

Collins, of the law firm of Collins, Collins, Muir & Stewart, remarked:

“I wish we did have an ability, like a labor union, to have a mass mailing.”

The advantage of a review of the candidates’ qualifications by a committee is that the members “dig” for information. If the County Bar held a plebiscite, he said, there would be some value in it, but he asked, rhetorically, “How many people, what percentage, would have an intelligent opinion?”

LACBA’s current president, Edith Matthai of Robie & Matthai, expressed doubt that it would be feasible these days to hold a plebiscite, given the size of the bar in Los Angeles County. “I can’t even imagine what the costs would be now,” she said.

The committee that evaluates candidates, Matthai said, is “one of the hardest working committees of the bar.” It seeks input from persons with “different perspectives,” obtains a “good cross section of opinion,” and “cross checks” information, she explained.

“The work that is done is accurate,” she maintained.

While consideration has been given to altering the approach to judicial elections, Matthai said, “the preliminary determination is that we’re not going to.”

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company