Tuesday, July 5, 2005

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

1960s: County Bar Urges Defeat of Judges Yager, Cannon

By ROGER M. GRACE

The Los Angeles County Bar Assn. in the 1960s urged voters to elect challengers to two controversial judges. But the power of incumbency proved mightier than the County Bar’s power of persuasion.

The two jurists whom the lawyers’ group wanted dumped were Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Thomas C. Yager and Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Noel (Nancy) Cannon. In the end, the bar association had one of its two wishes filled. Cannon was thrown out of office—not by the electorate, but by the Supreme Court, acting on the recommendation of the Commission on Judicial Performance.

Both of the challengers the County Bar endorsed—Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge George Dell, who took on Yager in 1966, and attorney Malcolm Mackey, who opposed Cannon in 1968—did ascend to the Superior Court later, and both became well regarded members of that body. Dell retired on Jan. 2, 1985, his 60th birthday, and Mackey remains on the bench.

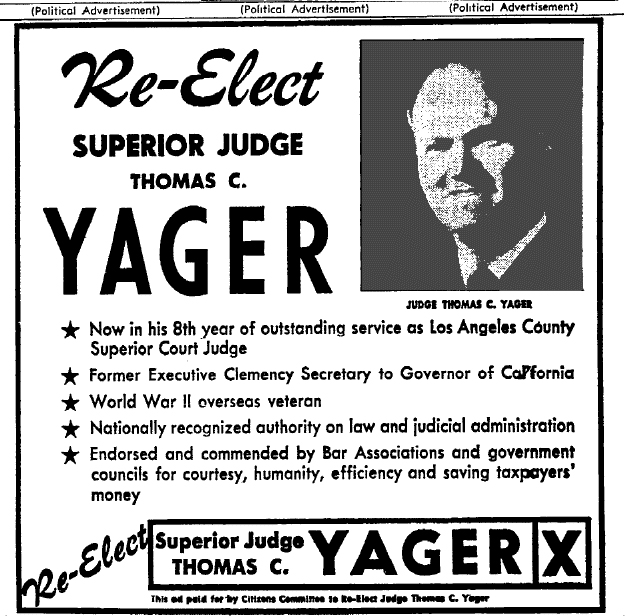

THOMAS C. YAGER was one of six judges of the Superior Court who were challenged in the 1966 election. He was the only one the Los Angeles County Bar Assn. did not endorse.

On June 6 of the previous year, the judge, then 47, was returning from Catalina to Newport Harbor on a cabin cruiser when his bride of four days, a wealthy 61-year-old heiress, disappeared, presumably having fallen from the vessel and drowned. Yager’s account was that he had gone below for a short time and when he returned to the deck, his wife was missing. He could not call the Coast Guard because, he explained, the radio was not functional. His recitation—justifiably or not—met with popular skepticism.

Yager was challenged by Los Angeles Municipal Court Judges George Dell and Leila Bulgrin (since deceased).

In those days, the County Bar came out with endorsements based on a tally of votes cast in a plebiscite. (1920 was the first year it conducted a plebiscite and made endorsements, and 1972 was the last.)

In 1966, County Bar rules precluded a LACBA endorsement unless a candidate bagged more than 50 per cent of the votes in the plebiscite for the particular office. Dell went over the 50 percent mark.

However, the advantage of the endorsements that year was minimized by virtue of the tardiness of the announcement of them, coming on the Thursday before the election.

If the announcement had come earlier, however, “it probably wouldn’t have made much difference,” Dell told me.

Nor did the Times endorsement, which he attained, matter much, Dell said, remarking that Yager’s incumbency was too hefty an advantage for him to overcome.

He might have had a chance, he reflected, if he had $25,000 or $50,000 in the campaign treasury.

“I had very little money, most of which came out of my own pocket,” Dell noted.

Yager’s campaign committee, on the other hand, at least had enough funds to run this ad in newspapers:

Yager told me last week that he did “hardly anything” in the way of running a campaign. He said he couldn’t recall campaigning by his competitors.

![]()

As to why he ran against Yager, Dell confirmed that public leeriness of the account of what had happened on the yacht “was part of it,” but added:

“Part of it was that he was not considered a particular asset to the bench.”

Dell characterized the incumbent he challenged as “lazy and indecisive.”

Be that as it may, Yager won outright in the primary. He drew 818,063 votes, Dell accumulated 366,759, and Bulgrin got 184,510.

The other challenged incumbents—George Dockweiler, Herbert V. Walker, Allen T. Lynch, Emmett E. Doherty, and Leopold G. Sanchez—also prevailed at the polls.

![]()

Yager remained on the court until his retirement in 1978. Shortly before he left the bench, he issued a press release announcing his forthcoming departure. When asked about it at the time, he acknowledged having drafted it himself. The press release said, in part:

“It was...learned that over five years ago Judge YAGER established a complete, new religion by the name of The Community Betterment Service.

“Religious scholars say they cannot recall another such instance in recorded history where a unique, entire religion was instituted by an active member of the judiciary....

“Judge YAGER smiled pleasantly when he said, in response to a question, ‘I expect to devote most of my time to serving the highest court—Almighty God.’ ”

He declined to talk about the religion when I asked him about it in 1978. In a brief telephone interview last week, he was consistent, saying:

“We have a religion but I don’t want to discuss it.”

Whether the religion is “unique” or not remains to be seen. What is definitely unique is the refusal of a supposed propagator of a religion to say anything about it.

Indeed, the only information about Community Betterment Service I could find on the Internet was mention of it is among numerous charities accepting donations of used autos. A check of the newspaper archives on Westlaw drew no articles alluding to the entity. Dun & Bradstreet reports that it has one employee which I assume is its president, Yager. There is no telephone listing for it.

Public records on Westlaw show that Community Betterment Service became a non-profit California corporation in 1974. (Until 1996, it was known as “The President of the Community Betterment Service, a Religious Corporation Sole.”)

Should you wish to become a member of the religion Yager founded, where would you find its house of worship? Well, secretary of state records show Community Betterment Service to be located at an address just outside Larchmont Village . I went there. It’s a gated Spanish-style house with bars on the windows, no religious symbols, no lettering—clearly not a place open to the public.

It’s on a corner lot. The house extends to the next block, and there is an entrance on that street. The address there is the one Yager uses as his home address.

In 1990, Yager transferred ownership of the house to the tax-exempt corporation. According to an attorney who’s also a real estate broker (in addition to being my daughter), it’s worth “about $1.9 to 2 million.”

![]()

Dell mentioned that his race against Yager proved to be a major factor in his gaining an appointment to the Superior Court on Sept. 23, 1966. It was an appointment that would not have been made—at least not on that day—had he remained in Anaheim at the State Bar Convention, as he had planned.

As it happened, he recounted, he’d seen enough, done enough, and returned to his chambers from Orange County at about noon. A call came from Gov. Pat Brown’s acting appointments secretary. The governor wanted to speak with him and would be calling later.

When the call came, Dell was on the bench, and by the time he recessed court and scurried back into chambers, Brown had gone off somewhere—but the acting appointments secretary told Dell the purpose of the call. The governor wanted him to take office that day as a judge of the Superior Court.

An incumbent had been up for election that year. However, he had just taken office as a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California and, it was determined, there would be an open seat, to be filled by the electorate, if Brown did not make the appointment that very day.

Dell related that the acting appointments secretary told him a couple of days later that she undertook to bring the governor the file that was on the top of the pile relating to applicants for the Superior Court. She had remembered that Dell sought to defeat “that awful Yager” and advised him: “You were sort of a hero—so your file was on top.”

NOEL CANNON sought reelection in 1968 as a judge of the Los Angeles Municipal Court. The County Bar urged voters to replace her with attorney Malcolm Mackey.

Mackey was one of eight challengers in the primary. In the plebiscite, the tally was 747 votes for Mackey and 658 for Cannon, with judge coming in third.

In the run-off, the Criminal Courts Bar Assn. backed Mackey by an 81 percent vote in its own plebiscite, and the San Fernando Valley Bar Assn. favored him by a vote of 48-19.

When Joan Dempsey Klein, then presiding judge of the Los Angeles Municipal Court, held a press conference on Feb. 15, 1968 to announce her candidacy for the Superior Court, she was questioned about Cannon. Mincing no words, Klein said:

“She’s a constant source of embarrassment to me and to every municipal court judge I know. We feel her conduct is not befitting a member of the court.”

(Klein lost the contest, notwithstanding the County Bar’s endorsement and that of the Times, but was later appointed to the Superior Court, and then to her present post as presiding justice of Div. Three of this district’s Court of Appeal.)

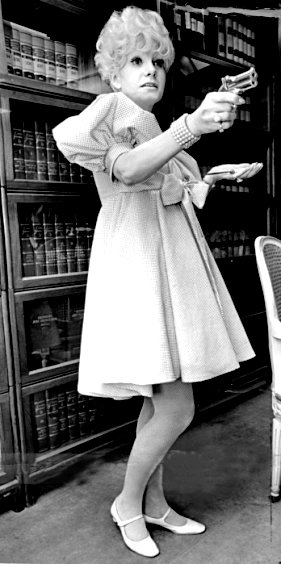

Three-fourths of the judges of the Municipal Court voted the previous year to censure Cannon based on her penchant for seeking publicity. Judges cited her having shown off her newly decorated pink chambers to reporters and appearing at a press conference to demonstrate devices women might carry to protect themselves, brandishing a derringer.

|

Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Noel Cannon is seen at a 1967 press conference she held in her chambers demonstrating weapons which women could use to defend themselves. Her right hand is holding a derringer and in her left hand is a hat pin.

Copyright 1967, Los Angeles Times, all rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. |

Cannon won the election by a vote of 485,911 to 360,092. As the Van Nuys News reported it:

“Judge Noel Cannon, famed for her short skirts and colorful extrajudicial comments, was an easy victor over Atty. Malcolm Mackey, a candidate backed by the Los Angeles County Bar Association.”

Mackey, who was endorsed by the Times, on Friday explained his loss by saying he was “outspent” by Cannon who, he said, had billboards and had her name on slate mailers. The judge said he spent only about $3,000-$4,000.

![]()

In years subsequent to the election, Cannon exhibited behavior that was bizarre.

It was in 1972 that a police officer pulled up beside her car and advised, after she rolled down her window:

“Ma’am, there is no reason to honk your horn. The gentleman was just waiting for a pedestrian, like he should have.”

Enraged, she told one bailiff: “Find the son of a bitch; I want him found and brought in right away. Give me a gun; I am going to shoot his balls off and give him a .38 vasectomy.” Like remarks were made repeatedly to another bailiff. When the officer was found and came to her chambers, Cannon told him: “You’ve been a very naughty boy” and gave him some religious literature to read.

![]()

According to a dissent in a 1994 Court of Appeal opinion which was depublished: “Noel Cannon had a mechanical canary in chambers [1972] and a live dog with her on the bench [1972-73], made a habit of locking up deputy public defenders, and once threatened to shoot her apartment manager [1974].”

The appellate court opinion that chronicled numerous instances of misconduct on Cannon’s part was the 1975 opinion of the California Supreme Court removing her from office. The per curiam opinion said that Cannon “has engaged in a course of conduct which has maligned the judicial office and clearly establishes her lack of temperament and ability to perform judicial functions in an even-handed manner.”

She died in 1998.

Mackey was elected to the Los Angeles Municipal Court in 1978, serving as presiding judge in 1985, and was elected to the Superior Court in 1988.

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company