Wednesday, June 29, 2005

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

1930s: County Bar Seeks Defeat of Eight Superior Court Judges

By ROGER M. GRACE

In 1988, the Los Angeles County Bar Assn. found Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Henry Patrick Nelson to be “not qualified” for his post. His challenger, criminal defense attorney Joe Ingber, was adjudged “qualified.”

In 1996, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Ronald Sohigian was also branded “not qualified.” One challenger, criminal defense attorney Charles Lindner, was rated “qualified” and another, civil attorney Ronald S. Smith, was found to be “well qualified.”

Despite being declared unfit by the county’s major association of lawyers, Nelson and Sohigian both prevailed at the polls. (Nelson later resigned rather than face Commission on Judicial Performance proceedings, while Sohigian is still at his post, to the displeasure of a large segment of the bar.)

The County Bar has rated, but not endorsed, judicial candidates in every primary election since 1976. But it used to do more. From 1920-72, it actually endorsed candidates, based on the outcome of a plebiscite, and publicized its choices, in some years devoting financial resources to advertising its slate.

Maybe efforts of that sort by LACBA in 1988 and 1996 would have resulted in the toppling of Nelson and Sohigian at the polls. ...Or maybe not. In years when the group actively pushed for the defeat of incumbents, it did not always succeed.

In 1920, the County Bar opposed four of the eight Superior Court judges who were up for election, and a separate organization recruited challengers. Two of those four targeted judges were defeated at the polls.

Thus, at the outset, the bar association showed its ability to effect the removal sometimes of judges it viewed as unfit.

It was also to demonstrate through the years only sometimes to protect worthy judges from removal through election challenges.

I’ll take a look today at the Superior Court judges the County Bar sought to defeat in the 1930s, and what became of them in later years.

![]()

In 1932, the County Bar (known until 1960 as the “Los Angeles Bar Association”) scored an election victory in the form of the recall of three Superior Court judges. However, it also endorsed three challengers to Superior Court judges who were up for election that year, with each of its recommendations being spurned by voters.

•Georgia Bullock was the first woman judge in California. Her bench experience began in 1922 when she sat as a judge pro tem of the Superior Court. She was appointed to the Police Court in 1924, and when that court was merged into the new Los Angeles Municipal Court in 1926, Bullock automatically became a member of it. While losing an election for the Superior Court in 1928, she was appointed to that tribunal in 1931.

Despite her incumbency, and the lack of any controversy concerning her, she fared miserably in the 1932 plebiscite—with Thomas B. Reed garnering 1,112 votes, Bullock attracting 289, and two other candidates gaining in excess of 100 votes each.

Voters nonetheless retained her, and she remained on the Superior Court until her retirement in 1955.

•Walter S. Gates faced three opponents in the primary. Of them, Justice Court Judge Thomas L. Ambrose, a former assemblyman, drew the highest number of ballots in the County Bar plebiscite—1,130—while Gates accumulated 348. He was implicated in the scandal over judges appointing receivers on the basis of getting something in return. Gates was indicted in July for accepting a bribe in the form of publicity services from a receiver he appointed. Later that month, a judge from Mono County acquitted him. Gates fought off the election challenge and retired from the bench in 1955.

•Thomas P. White lost in the County Bar’s poll to Police Court Judge James H. Pope, with the incumbent receiving 755 votes and the challenger getting 901 (with a smattering of votes going to two other candidates). White won and apparently did not prove a disgrace to his office. He was appointed to the California Supreme Court in 1959, serving until 1962.

![]()

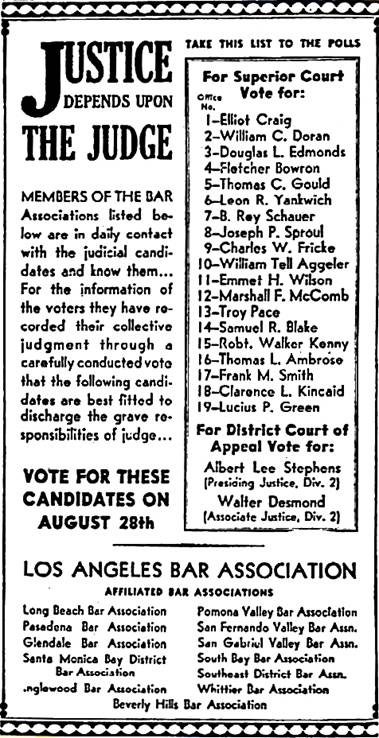

In 1934, the County Bar published this slate as an ad in newspapers:

No Municipal Court or Justice Court candidates were listed in the slate because, prior to 1952, candidates for those courts ran in odd-year municipal elections.

Missing quite conspicuously from the list of 19 candidates favored for the Superior Court were the names of two incumbents who had been challenged, Harry Sewell and Myron Westover.

•Harry F. Sewell had been a member of the Assembly from 1925-31. He was appointed to the Superior Court on Jan. 3, 1933 by Gov. James Rolph Jr.—who soon realized he may have blundered. On Dec. 28, 1933, Rolph reacted to press reports that Sewell had placed on probation a woman who had stolen $27,000 while sentencing a man who extracted $1 worth of nickels from a pay phone to 15 years in prison. Rolph commented that it “looks like strange justice.”

Then one day in May, 1934 Sewell appeared on the bench in a drunken state. That set off events leading to his political downfall.

Sewell drew five opponents in the Aug. 28 primary election. Votes in the County Bar plebiscite, tallied on June 17, showed Ambrose to be the clear favorite among those responding. He pulled 739 votes, while Sewell drew 315.

In August, Judge Fletcher Bowron, acting in his capacity as supervising judge of the criminal court, removed Sewell as the judge presiding over a hearing to determine the sanity of a man charged with murder, reassigning the matter to Judge Ruben Schmidt. Bowron acted in light of the numerous continuances occasioned by Sewell failing to show up for work. At a session preceded by Sewell’s heated argument with Bowron and Schmidt, Sewell got on the bench and declared a mistrial, then left. Bowron followed him to the bench, nullifying the order, with Schmidt, in turn, taking the bench to preside over the matter.

The County Bar, after considering internal reports, took the stance that “public interest would be served by the prompt resignation of Judge Sewell.”

Newspapers nationwide on Oct. 7, 1934, carried this Associated Press account, datelined Los Angeles:

“Superior Court Judge Harry F. Sewell, who for weeks has been presiding over an empty courtroom, was arrested and taken to the psychiatric ward of the general hospital. Should he be tried and found intemperate he would either be granted probation or committed to a state institution. The presiding judge had refused to assign cases to Sewell the last two weeks, alleging that he was intoxicated on the bench.”

The complainant was the proprietor of a sanitarium at which Sewell had been an outpatient since August. Two doctors signed the complaint as witnesses.

Sewell lost the election; was not institutionalized (possibly because the action against him had served its political purpose); was divorced in Las Vegas by “his pretty young wife” (as United Press reported it) and quickly announced his engagement to a court attaché many years his junior; and went back into law practice.

Ambrose was elected and served until his retirement in 1959.

•Myron Westover had been elected to the Superior Court in 1928, notwithstanding the County Bar’s support of the incumbent whom Westover, then a Municipal Court judge, challenged. In 1934, he drew three opponents. The outcome of the plebiscite was: attorney Troy Pace, 596; Westover, 511; attorney Allan L. Leonard, 43; and Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Hugh J. Crawford, 41.

Clout was lacking on the part of the County Bar in that election. It was Crawford, who had finished fourth in the plebiscite, who got into a run-off with Westover. Its top choice having been spurned by voters, the County Bar switched its allegiance to Westover in the general election.

In an article that appeared to track the wording of a bar association press release, the Van Nuys News on Oct. 10 said:

“Judge Westover, who has served on the bench since January, 1929, to date, is opposed by Municipal Court Judge Hugh J. Crawford, who was declared to be wholly unqualified, according to a [sic] overwhelming majority of the votes received on the association’s plebiscite.”

That was inaccurate. The plebiscite that year was a straight popularity contest—not entailing, as it did in some years, a rating of the candidates as “qualified” or “not qualified,” with endorsements going to those attaining the highest percentage of “qualified” votes. Crawford was not determined by the balloting to be “not qualified,” let alone “wholly unqualified.” In any event, Westover won the election and Crawford died the following year.

There was a love-hate sentiment on the part of the County Bar toward Westover. While it opposed him in 1928 as well as in the primary in 1934, it had endorsed him for a Superior Court judgeship in 1926 based on 82.9 percent of the 850 lawyers who voted finding him to be “qualified.” Westover lost the contest, but was appointed to the Municipal Court later that year.

In 1940, the organization backed Westover over his challengers, Los Angeles Municipal Court Judge Joseph L. Call (later appointed to the Superior Court) and former Assistant District Attorney Ugene U. Blalock, based on his receipt of the lion’s share of “qualified” ratings.

On April 23, 1946, the County Bar endorsed a challenger to Westover, Lt. Gov. Fred F. Houser. The statewide office-holder had been the unsuccessful 1944 Republican nominee for the United States Senate. His father, Fred W. Houser, who died in 1942, had served as a justice of the California Supreme Court.

In the plebiscite (this time not including a rating), Houser bagged 1,947 votes, Westover attracted 1,190 ballots, and perennial Superior Court candidate Ida May Adams, a judge of the Los Angeles Municipal Court, got 165 votes.

The Valley News observed that “[i]t is seldom” that a challenger “receives endorsement by the association over an incumbent.”

Houser was elected in the primary with 352,514 votes going to him, 164,672 to Westover, and 143,190 to Adams. He was the only judge elected to the Los Angeles Superior Court in the 1940s.

![]()

In 1936, two incumbents were opposed.

•Caryl Sheldon, who had been implicated in the scandal that resulted in the recall of three colleagues two years before, bagged only 284 votes in the plebiscite. However, as I noted in the last column, Sheldon overcame the County Bar’s adverse recommendation and went on to become presiding judge of his court.

•Charles L. Bogue was also mentioned here last time. Voters in 1932 recalled Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Walter Guerin, who had accepted gratuities from those he appointed to receiverships, and chose Bogue to replace him. Bogue apparently did not work out too well, and the County Bar proved persuasive in 1936 in urging that be replaced. Endorsed for Bogue’s seat was George A. Dockweiler, one of four contestants. Dockweiler was elected in November, remaining on the Superior Court until his retirement in 1968.

![]()

One incumbent was disfavored in the 1938 plebiscite, in which ballots went to all practicing attorneys in the county.

•Judge Edward R. Brand received 1,373 votes to 1,829 cast for Leo V. Youngsworth. The incumbent prevailed, serving until he retired in 1951, gaining a reappointment in 1954.

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company